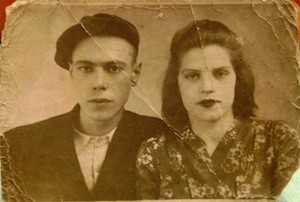

Survivor Mitzvah Project’s Zane Buzby, centre, in 2012 with Abramas and Malka Dikhtyar, the last two Jews in Bazaliya, Ukraine, the birthplace of Buzby’s grandfather. (photo from Survivor Mitzvah Project)

It is officially autumn and British Columbians are nesting, settling in for the cozier, slower season to come. For impoverished Holocaust survivors living in shocking squalor in eastern Europe, the impending winter is a time of danger and scarcity.

Like most people, Zane Buzby initially had no idea that there were thousands of destitute, aged survivors of the Holocaust living in subhuman conditions across the former Soviet Union. After she first encountered some of the poorest of the poor, she returned to her California home and searched for organizations that help them.

“I thought a lot of them must be doing this, even the big organizations that have Holocaust survivor programs,” she recalled recently. “I called every single one of them, [asking] specifically what are you doing? It’s nothing. They’re not helping people financially. No one was doing with this.”

The Claims Conference, which was created by the German government to aid survivors of the Holocaust, has proven useless to most of these individuals.

“If you were in a concentration camp – and the Germans kept really good records – if you survived Auschwitz, they have your name … [even so], most people have to hire an attorney,” Buzby said. The survivors she helps don’t have records, partly because the Holocaust in the east was typified by on-the-spot mass murder by Einsatzgruppen killing squads rather than concentration camps. And the few survivors in eastern Europe today do not have the resources to apply.

“They don’t have computers, they don’t have people advocating for them, there’s no lawyers out there,” said Buzby.

In many cases, they also don’t have the money to pay for heating fuel, let alone medications or doctors. Some may have a pension of $10 a month, others have no income whatsoever. Food can be very scarce and many of the survivors are the last, or among the last, Jews in their villages, making their final years bleak and lonely.

Buzby took it upon herself to help. She formed the Survivor Mitzvah Project in 2001 and has helped thousands of the most desperate, destitute survivors. (See also jewishindependent.ca/oldsite/archives/may08/archives08may02-01.html.)

“This is the last generation of Holocaust survivors and we are the last generation who can say that we helped,” she said. “Everyone turned their back in 1939 but today we can do something to help them and we should.”

The Survivor Mitzvah Project (SMP) doesn’t try to create the infrastructure of social services or initiate major projects. The goal is simple. Get some money into the hands of the most destitute Holocaust survivors as quickly as possible.

“We try to give them between $100 and $150 a month to get food, heat and medication, so it comes out between $1,800 and $2,000 a year per survivor,” she said. “Of course, we don’t have the money, we don’t bring in enough money, we don’t have enough donors to help everyone every month and that’s the sad part. That’s why this is really a call to action. There is no tomorrow for these people. They need money now.”

Buzby, an actor and TV director before she became obsessed with helping destitute survivors, finds recipients through word of mouth, traveling to villages and asking around for Jews or looking for signs of Jewish life. Often, she said, survivors lead her to others. She recalled a particular example.

“When I went there, to this little village, it was in such poverty, it was unimaginable, unbelievable poverty. No bathroom, no running water, no heat, broken windows,” she said. “A lot of these people made the huts they live in themselves out of mud and straw bricks after the war. It needs to be refurbished every year but now in their old age they can’t do it, so ceilings fall in. I gave [a woman] $800 and, on the way out, she pulls on my jacket and says to me through a translator, ‘Can I split this was someone?’ And I said, ‘Who are you going to split it with?’ ‘There is a woman down the road who is much worse off than I am.’ And I thought, how could anybody be worse off than you are, so I said come with us and take us to this woman. So we went to see the second woman and she was very bad off, so she was put on the list, and that’s how it goes.”

The Jews in these villages are often surrounded by non-Jews who are also destitute, said Buzby.

“There’s always poor people to help, God knows,” she said. “But for the Jewish people who survived the Holocaust, not only were their families decimated and murdered, their communities were obliterated, especially if they were in the east, they were burned to the ground. There’s no community, there is no rabbi, there’s no Jewish community, there is no shul, there’s no sister, brother and uncle, there is no support system. So, these [non-Jewish] villagers, even though they are also poor, they have large families, they have maybe a church, they have community. These [survivors] have no community. There is absolutely nothing supporting them.”

Holocaust survivors in eastern Europe have one thing in abundance, Buzby clarified. Antisemitism.

“Rampant. Terrible,” she said. “There’s more antisemitism now than there’s ever been.”

In places, neo-Nazis march openly on the streets. Fascistic parties are gaining strength across eastern Europe. In Vilnius, Lithuania, kids dress up as “Jews” in masks with exaggerated features that are perceived as Jewish and trick-or-treat, demanding money. War-era Nazi collaborators are being rehabilitated as national heroes, she said.

The relationships between the few surviving Jews and their neighbors is additionally fraught because of the high levels of collaboration between the Nazi invaders and the native populations in the east. The almost complete destruction of the Jewish communities of Lithuania – an estimated 95% of the Jews there were killed – is credited to the assistance of Lithuanians. The Simon Wiesenthal Centre has said that Ukraine, for example, has never initiated any investigation into collaboration or prosecuted a perpetrator.

The Survivor Mitzvah Project gets almost no institutional help. Buzby said she routinely contacts major foundations but they demur, saying they support various organizations that assist survivors. But the survivors Buzby has tracked down have fallen through the cracks of whatever institutionalized assistance might be available.

What they do get is support from some of Buzby’s show biz colleagues. Buzby’s acting career includes turns in some of the classic comedies of the 1970s and ’80s, including Up in Smoke, National Lampoon’s Class Reunion and This is Spinal Tap. As a director, she worked on sitcoms including The Dick Van Dyke Show, Golden Girls, Newhart and Blossom. She has brought entertainment figures together for emotional events in which luminaries including Valerie Harper, Ed Asner, Frances Fisher, Elliott Gould, Lainie Kazan and Chris Noth read letters from survivors SMP has helped, who speak about their hardships and the difference the assistance has made in their lives. A powerful video of one of the events is online at survivormitzvah.org.

SMP has hit the $1 million a year mark, but Buzby estimates she needs $2.5 million to meet demand.

“This is an opportunity for people to change the course of history for the survivors,” she said. “Everybody has monuments and raises money for and builds museums for remembrance of those that perished, which is absolutely as it should be. But what about those that survived?”

The coming of the cold winter adds urgency to Buzby’s work. So does the obvious march of time, she said, as the remaining survivors near the end of their lives.

“It’s a time that’s never going to come again,” she said.

For more information or to donate, visit survivormitzvah.org or canadahelps.org.