“Shabbat Saskatchewan,” by Esther Tennenhouse. Part of Otiyot (Letters), a joint exhibit with her son Joel Klassen, which is now at the Zack Gallery.

Colourful and playful, dark and ominous, Esther Tennenhouse’s artwork is engaging and thought-provoking, as she offers her take on Torah and midrash, immigration and language, orthodoxy and modernity. Otiyot (Letters), an exhibit she shares with her son Joel Klassen, opened at the Zack Gallery last week.

Tennenhouse’s sense of humour, curiosity, imagination and sincerity come through in the work on display, and in her responses to questions about the exhibit.

“Ot means ‘letter’ (of the alphabet) – it also means ‘sign’ and ‘signal,’” she told the Independent. “It was my first choice of name for the show: Ot – Starring the Letter Shin. Sounds like ‘ought,’ as in ‘thought.’ Ot was visually terse (and sounds adorable). That was why it was Ot in [the] JCC program book – I had to provide that bit before these pieces were made! Yikes! But it got changed to the longer plural in Hebrew and lost its zap. More truthful, though, as I have so many (too many) words of explanation on the wall beside each piece.”

All the works were made specifically for the exhibit, said Tennenhouse, “only for this place, for anyone who happens to walk into the JCC,” where the Zack Gallery is located.

“I was driven by my own relationship to the alef-bet: me, a quite secular, second-generation, Winnipeg-born Jew living in Vancouver, of prairie-born parents, who learned my aleph-bet as a child, quite long ago. I think many like me, with my sort of education, walk by these gallery doors, so I thought they might wander in and relate.”

Born and raised in Winnipeg, Tennenhouse went to Talmud Torah there from age 4 to 11, then to public school. She earned a bachelor’s in English and, while working at the Winnipeg Free Press, majored in sculpture at the University of Manitoba School of Art.

She moved to Aklavik, in the Inuvik region of the Northwest Territories, and then to Yellowknife, where she learned about ceramics at the Yellowknife Guild of Arts and Crafts. She later worked with translucent clays.

Moving with her family – husband Ron, son Joel and daughter Timmi – to Vancouver in 1995, Tennenhouse found a home at Or Shalom, participating in the Talmud and Torah study offered there, reengaging in Jewish education after a break of some 45 years.

Klassen also attends Or Shalom. His art background includes having drawn at home and working with painter Sylvia Oates – who he describes as a mentor – in her Parker Street studio. Klassen has had a one-man show in artist Noel Hodnett’s Parker Street studio, and he was in the Kickstart Disability Arts and Culture’s 2019 group show Nothing Without Us at the Cultch. For the past four years, he has attended the JCC’s Art Hive, which is facilitated by Kim Almond.

Klassen’s Hebrew letters and drawings are in five of the pieces at the Zack Gallery, said Tennenhouse.

“Making letters as individuals, each with their own character, was the most fun to do,” she said. “Jan Wilson, a friend and quilter, offered to help if I drew out the correctly sized letters backwards for transfer and picked the fabrics.”

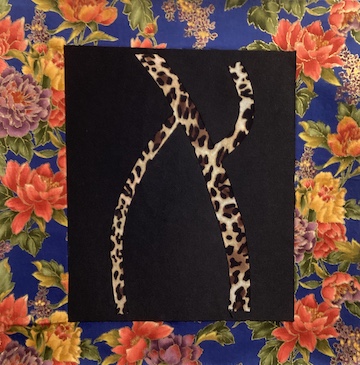

The letters comprise eight of the works on display, and offer much to think – and smile – about. Klassen’s aleph is filled in with leopard print fabric, surrounded in black with a flowered border. The word “wild” comes to mind as one looks at it, not just the wildness of animals and nature, but of human beings. The piece is called “Aleph in the Garden.”

“I did not shy away from diversity,” said Tennenhouse. “It’s sort of an underlying element. I felt the show had to offer something to any individual, whatever their history with the alef-bet, and it deals with very well-trodden themes. I felt a need for an element of surprise, which is one reason why Joel’s aleph became a leopard in the garden (of Eden?).”

A last-minute addition to the depictions is one of the 12 new letters for gender-neutral word endings that were created by Israelis graphic designer Michal Shomer a few years ago.

“They appeared in welcome signs outside schools and on IDF buildings, etc., but the kabbalist idea of the power of the alphabet lives on – the new letters were vigorously rejected by religious factions,” said Tennenhouse. “‘Changing the letters removes any kedusha (sanctity) the words have or any ability the words have of channeling God’s energy into the world,’ said sofer Rabbi Abraham Itzkowitz. ‘This project essentially makes Hebrew like any other language.’ Some of the signs were taken down. Religious schools were forbidden to use them.”

That said, Tennenhouse told the Independent, “What first tickled me into this aleph-bet project was the poetry and passion of the ideas of the early mystics. They conceived of letters of the alef-bet existing even before the creation of the world – all 22 were vessels of the divine, all things were created by their combinations. Meditative/ecstatic kabbalah taught that individual letters were something to meditate upon, which led to ecstasy, one of the steps to sense of union with G-d. American calligrapher Ben Shahn, who titled one of his books Love and Joy About Letters, quotes the 13th-century Rabbi Abulafia, who said the delight in combining letters is like being carried away by notes of music.”

Tennenhouse and Klassen’s “Shir” (song, poetry, chant, in Hebrew) is truly delightful, like a page out of a children’s book. A multimedia piece, it depicts several animals and the sounds they make, both in Hebrew and in transliteration, though the giraffe just “hum[s] at night.”

Two other works are striking, both on their own and in contrast to each other: Sinai 1 and Sinai 2.

The latter features three bright yellow flowers, surrounded by green. “It is a triangle canvas which is about the mountain bursting into bloom when Moses came down with the Ten Commandments – this was a midrash from the 1500s. The triangle has flowers by Joel. I asked him to put flowers on it, envisioning little flowers here and there – he just went swoosh woosh on it.”

Sinai 2 is a vertical rectangle with whites, greys and blacks depicting a furious ball of activity on top of the mountain that includes the Hebrew letters.

“The Torah tells of fear, awe, the shaking mountain, seeing sounds, lightning, Moses’ anger, the breaking tablets,” said Tennenhouse. “Looking back, I overburdened the canvas [with] anger, though laying on the 231 Gates – a diagram from the Sefer Yetzirah which shows each letter combining with each other letter of the alef-bet – because I see the story of the giving of the Torah as a sort of creation story for our intense embrace of literacy. The diagram relates to Rabbi Abulafia’s talk of combination of letters but distracts visually from the anger/violence, [the] mountain, fear.”

There is so much more in this exhibit.

“Cursive Handwriting: Kovno Testament” is a stark, unfinished work, featuring the words, written in his own hand, of Lithuanian writer Eliezer Heiman, who died in the Kovno ghetto during the Holocaust. It was to have three more samples of cursive, said Tennenhouse. “I left room for them before I put on the image of Heiman’s tablets. Those spaces stayed empty. Everything else edited themselves out because of what happened in Israel on Oct. 7.”

There is the multimedia triptych “Shabbat Saskatchewan,” which Tennenhouse said “is me trying to use real photos and documents to create some presence of my mother’s grandparents and parents.”

“It ended up being centred on great-grandmother Esther Dudelzak Singer, Baba Faige (Fanny) Singer and my mother with her sisters,” she said. “Yiddish was their mamaloshen (mother tongue) and the Sonnenfeld community was religiously observant.”

“The Owl and the Pussy Cat” adds colour and vibrancy to Edward Lear’s black and white drawing of his nonsense poem, the Yiddish translation of which – by the late Marie B. Jaffe – fills the two side panels of this triptych. Tennenhouse couldn’t find much information out about Jaffe, she said, “But, thanks to Eddie Pauls at the Jewish Public Library in Montreal, [I] learned she immigrated to New York in 1909 from Lithuania.”

Tennenhouse began to see the owl and the cat in their boat as sailors braving the rough seas, traveling around the world to find “Di Goldene Medine,” “the Golden Land,” America.

“You might say ‘Saskatchewan,’ too, is about leaving home, traveling across seas and finding a new place but keeping your language and culture,” said Tennenhouse.

Otiyot (Letters) is on display at Zack Gallery until Nov. 12.