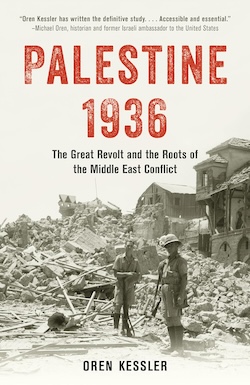

The historic milestones that led to the creation of the state of Israel are well known: Theodor Herzl’s Zionist congresses, the Balfour Declaration, the Partition Resolution, the War of Independence. Oren Kessler – who participates in the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival on Feb. 13 – believes that a significant chunk of history has been largely overlooked and he sets out to right that wrong in his new book, Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict. The Arab uprising of 1936 to 1939 in Palestine, he writes, “was the crucible in which Palestinian identity coalesced.” It also set in stone the intransigence toward Jewish self-determination in the region.

An Arab reaction to increased Jewish migration to Palestine – presaging both the potential for an eventual Jewish majority in the British-controlled Mandate and an even more alarming political outcome, a Jewish national homeland – inspired three years of Arab terror and British colonial repression, with the Jews inevitably caught between, argues Kessler.

An Arab reaction to increased Jewish migration to Palestine – presaging both the potential for an eventual Jewish majority in the British-controlled Mandate and an even more alarming political outcome, a Jewish national homeland – inspired three years of Arab terror and British colonial repression, with the Jews inevitably caught between, argues Kessler.

Beginning with a series of strikes and protests in April 1936, the haphazard opposition to British rule and Jewish immigration was soon corralled and led by the notorious Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, into a mass movement of terror and anti-colonial (and anti-Jewish) violence.

While the British, on the one hand, hammered the Arab guerrillas – and plenty of civilians – they also rewarded that violence with policies such as those emerging from the 1937 Peel Commission report and the 1939 White Paper, both of which effectively caved to Arab demands by massively reducing Jewish immigration just as the Nazis were closing their fists across Europe. At the same time, the British left the Arabs unsatisfied by throwing tiny offerings to the Jews as a sign of compromise.

So unyielding was the mufti’s opposition to even considering Jewish migration that his Arab Higher Committee boycotted the various commissions’ hearings.

“Amid Hajj Amin’s boycott, no Arabs came forward,” writes Kessler. “Jerusalem Vice Mayor Hassan Sidqi Dajani, the mufti opponent who had once contemplated testifying, was found along the train tracks outside the city with two broken hands and two bullet holes in his forehead.”

In the end, the revolt was a disaster for everyone.

“The great revolt had exacted a withering toll on Palestine,” writes Kessler. “About 500 Jews had been killed and some 1,000 wounded. British troops and police suffered around 250 fatalities in their ranks. But the most onerous price of all was paid by the Arabs themselves: at least 5,000 – perhaps more than 8,000 – were dead, of whom at least 1,500 likely fell at Arab hands. More than 20,000 were seriously wounded.”

The Arab economy in Palestine was ruined, even as the Jewish economy hummed along.

Kessler’s thesis is that the events of 1936-1939 deserve to be recognized more as pivotal to the history of the region as a whole. There are also voluminous parallels and lessons for contemporary times in his review of that era.

The uprising did not, in the end, prevent Jewish national self-determination in Palestine. What it did prevent was a refuge for the Jews of Europe when they needed it most – and, for at least some of the players in this tragic drama, like the Hitler-allied mufti, perhaps that was a reward in itself.

The Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival runs Feb. 10-15. For tickets, visit jccgv.com/jewish-book-festival.