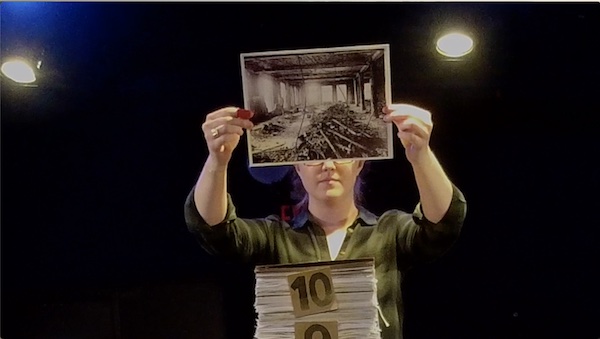

Surplus Production Unit’s Briony Merritt. (photo by Alex McLean)

No matter how well we document history, it matters little unless people are aware of it. Two very different productions at this year’s Chutzpah! Festival, which began this week, were born of personal discoveries of documents from the past – in one case, a trial transcript; in the other, Yiddish compositions. The artists’ unique interpretations help ensure that important aspects of our culture are not forgotten.

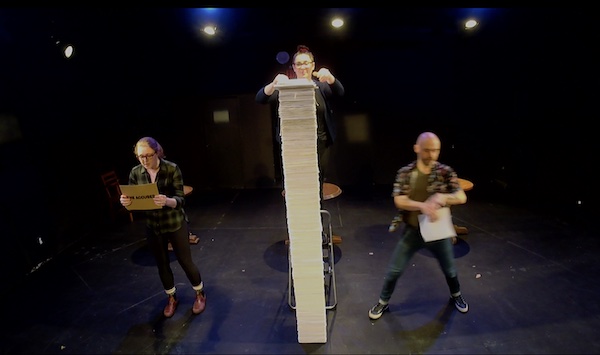

Halifax-based Surplus Production Unit, under the direction of Alex McLean, performs A Timed Speed-Read of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Trial Transcript on Nov. 21 and 22 at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver, in the Wosk Auditorium. Montreal’s Josh “Socalled” Dolgin performs music from his album Di Frosh with a local quartet at the JCC’s Rothstein Theatre Nov. 19 in a concert that will also be livestreamed.

“I had never heard of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire until 2010, when I was doing research for an MA in Toronto,” McLean told the Independent. “I was totally fascinated by the case and got especially swept up in the extensive trial transcript.”

Triangle Shirtwaist Company owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris were put on trial for manslaughter after a fire at their factory on March 25, 1911, killed 146 people – mostly women and girls – in part because one of the exit doors was locked.

“I think the gender politics were what initially stood out to me – it was an all-male jury, the case hinged on the discrediting of female witnesses, and it was all taking place at a time when women weren’t able to vote in either Canada or the United States. I also knew that this was a time when the labour movement was massive globally and that the Ladies Garment Workers Union had waged its major strike just a couple years earlier. The way that this all reads as subtext in the trial transcript was fascinating to me. I knew that I wanted to work with the material somehow, but wasn’t sure how.”

In 2011, during the 100th anniversary year of the fire, McLean saw an interview with Charles Kernaghan, director of the Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights, who mentioned the Hameen factory fire in Dhaka, Bangladesh. “And then there was the Tazreen factory fire in 2012 and then the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Dhaka in 2013,” said McLean. “It all made the record of what happened in New York in 1911 hauntingly relevant.

“Somewhere around this time,” he said, “I got a small grant to create a verbatim script from the transcript. I started work on it but it felt lifeless, like a bad ‘historical drama.’ So, I gathered a few actors who I knew and trusted and who were interested in the material. We started playing around with ways to approach the material that felt honest and the current production grew from there.”

McLean believes “it is endlessly worthwhile to think about the hidden costs in our global economy and the conditions under which so many of the products we consume are created.” At the same time, he added, “I was very aware that my life – like those of my colleagues – was radically different from the lives of the people in the trial transcript. None of us are immigrants, none of us are Jewish or Italian (as were almost all of the Triangle victims). As middle-class Canadians in the 21st century, I felt that we had to acknowledge the gulf between us and those New York factory workers in 1911. We had to build this distance into the structure of the show, and so this idea emerged that we would actually sit the trial transcript on the stage and the performance would be a group of people engaging with this historical record, rather than trying to represent it realistically. This felt like the only way we could approach the material respectfully.”

Throughout the trial, said McLean, “witnesses, especially women, were treated with palpable disrespect. Max Steuer, the lawyer defending the factory owners, repeatedly tried to cast suspicion on witness testimony. This came to a head in his cross-examination of Kate Alterman, the ‘star witness’ for the prosecution. Knowing that Alterman’s English wasn’t great, Steuer had her repeat her testimony multiple times to make it appear rehearsed. This ultimately worked for him.

“There’s also a fascinating class dynamic at play: Steuer and his clients, Isaac Harris and Max Blanck, were themselves Jewish immigrants who had worked their way up in New York’s garment district. While at times they appear callous towards the victims and survivors, there is also this sense that they come from the same place. The prosecutor, on the other hand, comes across as much more of a patrician and, at times, this results in condescension. To him, the victims are helpless little girls, while the defence tries to portray them as streetwise conspirators plotting their revenge. Their actual messy humanity gets lost in the crossfire.”

Justice was not served by the trial, nor other legal measures, but there were positive changes that resulted from the tragedy.

“Part of what the case revealed was that workplace safety regulations at the time had no teeth, so the silver lining was that a host of new laws were introduced,” explained McLean. “Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in a U.S. cabinet, actually witnessed the Triangle Shirtwaist fire and described it as a pivotal moment in her life. She became secretary of labour under FDR [Franklin D. Roosevelt] and was a major player in ushering in the New Deal.”

In terms of lessons learned, however, “we seem doomed to continually forget the inequality that animates our world,” he said. “Going to work under dangerous conditions seems like a reasonable choice to many people in impoverished conditions. As long as those conditions exist, workplace tragedies are likely to occur.”

He added, “There’s a fascinating historian of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire, Michael Hirsch, who argues that it’s a mistake focusing anger and blame on the factory owners. He uncovered the names of several bodies that were unidentified in 1911, and he makes a yearly pilgrimage to the victims’ graves…. To me, Harris and Blanck do appear negligent, but acknowledging systemic imbalances is also important. Economic inequality has proven a difficult problem to solve, but that doesn’t give us the right to forget about it. My sense is that we need a new New Deal today.”

A love of Yiddish music

Josh Dolgin has many artistic interests and musical styles – from composing to photography to puppeteering, from hip-hop to musicals to Yiddish music. As different as they may be, Dolgin said, “all the passions stem from an attraction to ‘realness,’ to things that just deeply move me, spark inspiration, speak to my soul.”

For him, the 2018 album Di Frosh “was a kind of return to a pure, more ‘traditional’ Yiddish music, even though it’s a project of ‘new’ music. I had experimented with using Jewish music sounds in contemporary ways,” he explained, “sampling, mixing, collaborating and fusing to create hip-hop, rap and funky pop music. In so doing, I became rather immersed in the form – in klezmer, in Yiddish folk, art, theatre music, cantorial sounds from the synagogue and Chassidic music – by collecting old records looking for sources. Listening to all that music, I eventually fell in love with the source material … I wanted to play and sing it! I eventually started learning the songs as a pianist, as an accordionist and singer. I wanted to just perform that music, without mixing it, without adding beats, just to play and sing it as is.

“In the meantime, I started getting into four-part harmony singing and collecting choral arrangements, then directing choirs at synagogues and music camps. That love of harmony mixed with my love of singing Yiddish songs and I thought, hmm, it would be cool to present this repertoire in an almost classic style, maintaining all that beautiful real harmony from arrangements from the ‘time.’ Some friends and I created new arrangements based on old sources – all the arrangements are ‘new,’ this repertoire for string quartet never existed before, so it’s ‘new’ music, but it’s more traditional than my fusion/pop experiments.”

Dolgin went to Hebrew school and was raised Jewishly. But, while he “adored” the “holidays and rituals and foods and songs,” he said, “I never was very inspired by the religious aspect of my cultural history, or the establishment ritual practice. When I started to find old records of Yiddish music looking for samples to make hip-hop music, I had stumbled on a part of my cultural identity that I could take pride in, that spoke to me, something I had never been exposed to with the more ‘mainstream,’ ‘modern,’ ‘reform’ version of Judaism I had experienced as a child.”

Musically, he started piano lessons at a young age and “was bribed and forced to keep at it, until I finally was allowed to study ‘jazz,’ i.e., not classical music. Then I got into the ‘rap music’ of my peers, and wanted to participate in that, to make a current music from today. I started looking into studio production techniques, sampling, using drum machines and computers to sequence and combine sounds and compose. Finding the Yiddish sounds and repertoire gave me a voice in hip-hop culture.”

Dolgin has always been one to seek out things that were “off the beaten path” and “a bit more hidden.”

“That led me as a teenager, in the days before the internet, to develop a real love of Brazilian music and funk, by digging and exploring,” he said. “The digging required to find sounds to sample in hip-hop led me unearth … a whole universe of Yiddish music and culture. I never heard Yiddish growing up! I had no idea! It was so fun to discover these treasures of my own cultural history, these sounds, modes, rhythms, poems and songs that were developed by my Eastern European ancestors. I dug around and really got into trying to find as much as I could, and that was more fun for me than having a whole repertoire handed to me on a silver platter.”

Dolgin chose his favourite songs for Di Frosh, ones “that weren’t the same top five Yiddish ‘chestnuts’ that everyone has already sung. Even though it’s not at all a well-known repertoire, there are a few songs that keep coming up, and they’ve been sung and presented enough, thank you very much. I wanted cool, rare repertoire. These could be things I heard from old records, or things I found as piano and choral arrangements on paper that could be brought to life in new arrangements.

“I thought it would be nice to have a range of repertoire from the various sub-genres of Yiddish music, from theatre music, from folk song, from Chassidic song, from postwar things, Holocaust songs, and even some ‘originals’ from contemporary Yiddish writers. Those ‘high concept’ factors were at the back of my mind when putting the program together, but it was mostly just a very subjective process of picking my favourite songs, the songs that blow my mind lyrically, harmonically or melodically.”

He went through another selection process when he was asked by a bass player from Vienna to do some Yiddish songs with a big band. Dolgin said he picked “out a whole new repertoire of more Yiddish songs I was interested in presenting, sent charts and recordings to them and they created arrangements for an actual 19-piece big band! I showed up in Salzburg and, after one rehearsal, performed with them to a sold-out jazz festival audience – it was magical! We have since done the show several times, including this summer with the Toronto Jazz Orchestra for the Ashkenaz Festival.”

They were about to travel with the show in Germany and Austria when COVID struck; the plan is now for a spring tour. During the lockdowns, said Dolgin, “I did manage to write quite a few more arrangements of Yiddish songs for string quartet, so hopefully a Frosh 2 is possible.”

The best part of this project, he said, has been “meeting new string quartets around the world and bringing this new repertoire to them, and then bringing the music to new audiences who may not be too familiar with these songs, with these sounds.

“After recording the music to make the Di Frosh record, with the amazing Kaiser Quartett based in Hamburg,” said Dolgin, “I’ve since presented this music all around the world with ‘local’ quartets: in Vienna, in London, in Venice, New York, Toronto, Montreal, Boston, Paris…. I’m very excited to be in Vancouver and meet Elyse Jacobson and the musicians she will put together for this program.

The Chutzpah! Festival opened Nov. 4 and runs until Nov. 24. For tickets and the full lineup, visit chutzpahfestival.com or call 604-257-5145.