Hidden in the spine of a 1947 edition of Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl, in its original Dutch, is a piece of paper with the German words, “Die Vergeltung,” or retribution. (photo by Shula Klinger)

I ran into Richard Smart in North Vancouver in early September. It was at Urban Repurpose, a nonprofit store that sells used building materials and an eclectic mix of donated household items. Many of these items are vintage and, if you’re interested in local history or looking for artistic inspiration, it’s also a treasure trove.

Employing skills handed down over three generations of his family in England, Smart restores and sells antique books using tools that have “barely changed for centuries.” And, since a homeschooling mom never misses an opportunity to educate the children, I asked him if we could come by the Old English Bindery to see him at work. In mid-October, he invited us to see how a broken book could be repaired.

Smart showed us book presses, tools for applying gold leaf to the bindings of books, piles of ancient, beautifully decorated papers and, of course, the books themselves – travel writing, fiction, nonfiction, massive tomes of human anatomy, bigger than any book you’d see in print nowadays. He also applied gold leaf to the kids’ index fingers, which delighted us all.

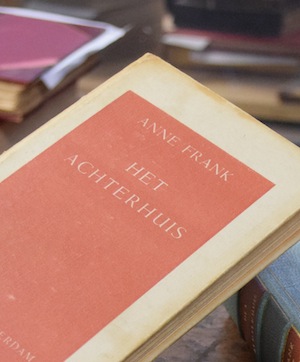

Just before we left, Smart showed me a small, bubble-wrapped book. I looked down as he held it out. Its title: Het Achterhuis. Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl.

“It’s a first edition,” he said. There was a pause, to let this information seep in. He pointed to the front left edge. “I only did minor repairs on it, here.”

I stared at my hands, holding this 1947 edition of The Diary of a Young Girl, in its original Dutch. Looking down, just breathing. Thinking about how, a mere two years before this book was published, Anne and her sister Margot were still alive. In captivity, but alive. Anne was still writing, contemplating the nature of the human soul.

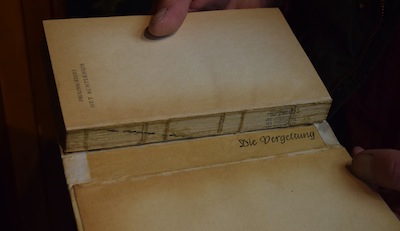

A moment later, Smart pointed to the inside of the spine, where it had separated from the contents. “Look at that,” he said, and pointed to some words in German: “Die Vergeltung.”

“I looked it up,” he said, and here he became animated. “It means retribution. Or payback.”

I was already choking back the emotion of holding this 70-year-old edition of The Diary, but now this?

I asked how the text had gotten there, when the book had come apart, if it had been placed there during the original binding.

“Bookbinders often used scraps of paper to pad the inside of a spine,” he explained. “But to choose this particular piece of paper? Just think about that.”

By then, my head was full of questions, all competing for my attention. Unfortunately, my two children were also competing for my attention. The little one was extremely curious about the book presses, but the big one was edging toward the door. Also, as interested as they are in world history, this wasn’t the time to tell them about the Holocaust, so we left.

Over the next few days, I learned more about the book’s earlier life and Smart’s plans for its future. “This book needs to go back to its community,” he said. When asked if it there had been any fanfare at the Dutch auction, he said, “It was just an ordinary estate sale.”

Since the original dust jacket was missing, Smart has made a case for it. Working to match it to the cover’s original colour, he chose a pale blue leather inlay for the lid and patterned, or “paste,” paper for the sides.

I also wrote to Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. Gertjan Broek replied, saying, “There are still a few mysteries around the first edition of Anne Frank’s Het Achterhuis.” He agreed that “randomly available” pages from other books were often used to pad spines – “paper was a scarce resource in those years,” he noted.

This was probably the case with the page used in Smart’s edition of Het Achterhuis. Die Vergeltung was published in Bayreuth, Germany, in 1941 and reprinted in 1944. In Broek’s view, the typefaces were a match. Broek didn’t know if this was true for all of the 3,000 books in this first run, but he said he’d ask his colleagues.

A few days – and a good deal of anxious email-checking – later, Broek wrote again. “Three experts in book restoration have told me they have never seen a first edition copy of Het Achterhuis with this kind of print.”

And that is where the story rests, for now. I would love to paint a more detailed picture of the bookbinder at a workbench in 1947. I picture hands cutting out a page of that German book, laying it into the backbone of Anne’s book. Was the bookbinder just doing a job, or taking a degree of satisfaction in leaving a deliberate, but hidden, commentary inside this now-iconic piece of work?

There’s another layer to the tale.

In an age where people are rushing around permanently plugged into an online world, bookbinders like Smart have an unusual job. Every day, instead of racing ever forwards, he steps into worlds that have passed, touches books first purchased by people who haven’t lived for centuries. As he preserves their books, it’s as if he offers a passage between their time and ours.

Amid all of these remarkable works, Anne’s stands out as a beacon. “Books like Anne’s make this work worthwhile,” said Smart, who is keen to sell his copy of Het Achterhuis, but to an organization, not a private individual. “I had an offer on it but I refused it,” he said. “I have my heart set on it going into an institution that will display the story.”

So, in preserving precious books, Smart is doing far more than simply offering a service, repairing material goods. He is acting as a guardian of history.

Smart also wonders about the binder of this copy of copy of Het Achterhuis, “the moment of looking for a spine liner and putting that particular one in. What was going through his mind, in 1947?” On reading this in Smart’s email, I replied that, really, the book was priceless.

Later that day, he emailed again. “This one copy is priceless, as you say. Not financially but historically. Just imagine the story told by everyone that sees this book in a museum. It would bring people in, just to see this, and talk about it. That is worth so much for everyone in this world.”

Responding to my expression of gratitude for his professional conscience, he said, “Faith is everything.”

Shula Klinger is an author, illustrator and journalist living in North Vancouver. Find out more at niftyscissors.com.