Dr. Robert Krell, left, listens to Prof. Elie Wiesel, as Wiesel addresses the capacity crowd that came to the Orpheum in 2012 to hear him speak (photo by Jennifer Houghton). Elie Wiesel passed away on July 2. May his memory be for a blessing.

The following article was originally published on Sept. 21, 2012, and initially reposted on July 2, 2016. The photographs were added with its republication in the newspaper and online July 15:

“The Jewish people is based on what is called in the Prophets, ‘Edim atem l’Hashem,’ ‘You are witnesses to God.’ Says the Talmud something horrible: the Talmud says God says, ‘If you are my witnesses, I am your God. If not, I am not your God.’… That is the importance of testimony.”

This was part of Nobel Peace Prize-winner Elie Wiesel’s response to a question about the role of March of the Living alumni. “You are now the witnesses,” he said. “Remember, to be a witness to the witness is as important as to be a witness.”

Wiesel was in Vancouver to launch the Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver’s annual campaign on Monday, Sept. 10. The event, which was held at the Orpheum, featured Wiesel in conversation with his friend, fellow survivor Dr. Robert Krell, as well as a presentation of another of Wiesel’s friends, Robbie Waisman, who accompanied this year’s March of the Living program to Poland and Israel. Participant Jenna Brewer read the account written by Monique de St. Croix of Waisman’s emotional return to his birthplace, after which Waisman himself addressed the nearly 2,700 people in attendance.

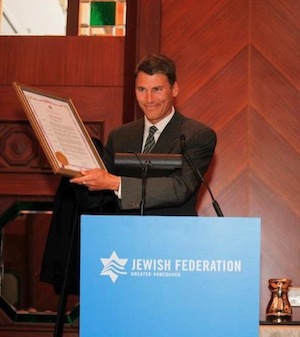

The campaign launch was the culmination of Wiesel’s day here, which included a proclamation from Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson declaring Sept. 10, 2012, Elie Wiesel Day.

Among Wiesel’s many activities was the receipt of an honorary degree from the University of British Columbia, where he spoke to university administrators, students and Holocaust survivors. A formal academic procession led Wiesel into the hall and a short panel discussion followed his remarks, involving the university’s president, Prof. Stephen Toope, Prof. Richard Menkis, a professor of modern Jewish history, and Barbara Schober, a graduate student. UBC Chancellor Sarah Morgan-Silvester presented Wiesel with the doctorate.

Also on Wiesel’s itinerary was a morning interview with the Jewish Independent; one of only two interviews he granted while here, the other being with the Vancouver Sun.

As editor Basya Laye and I introduced ourselves, Wiesel admitted his dependence on the New York Times, a copy of which he had not yet picked up that day. Once the “bible of journalism,” according to Wiesel, he lamented the Times’ decline in quality as the newspaper industry itself has declined. He wasn’t worried about the change to internet media, however.

“Our stories are not dominated by concern with the press, it’s person to person,” he said. “If you relied on the New York Times, the New York Times’ background, record in those years, is not the best, during the war.”

Wiesel recounted how, years ago, he complained to the Times about how little there was in the paper about the Holocaust while it was happening. Subsequently, he was invited to a luncheon, at which he gave them a piece of his mind. As a result, said Wiesel, in the paper’s offices, they have a plaque/letter saying, “We failed,” as a reminder to themselves.

Yet, admission of failure on the world level – that countries did not do enough to prevent the Holocaust – has not resulted in the prevention of other attempts at genocide.

“Can human nature change?” Wiesel said about that fact. “It’s society. Whatever the issue we have is, for instance, believe me that, I say, a sex story will have the front pages. Not what we try to say, but the sex story will have the front pages. It is our culture. We go with what is easy, what is cheap, and what is accepted as interesting by more people than before. And that goes everywhere, that’s in literature, that’s in the movies. I don’t know where we are heading.”

For his part, Wiesel has spent most of his life – as a witness, storyteller and teacher – trying to ensure that “never again” is a promise kept.

Born in Sighet, Romania (which was in Hungary during the war), Wiesel was 15 when he and his family were taken to Auschwitz. His mother and younger sister were killed there, his father died in Buchenwald, where Wiesel also was imprisoned when the war ended; his two older sisters survived. Wiesel’s book about his experiences in the camps, Night, was first published in 1956. It has since been translated into more than 30 languages, with millions of copies being sold.

A professor at Boston University since 1976, Wiesel was founding chair of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, which created the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, and, with his wife, Marion, he established the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity soon after he received the Nobel. He has written more than 50 books, and his lengthy resumé continues.

When asked how he would categorize his body of work, Wiesel told the Independent, “Not enough.”

“What would you like to have been able to do?”

“More.”

“In terms of?”

“More,” he repeated. “Not enough. Look, look, on the surface, I’ve done a lot, published many books. Many books have been published about me, and so forth. I have approached presidents and kings, but all of that, somehow, it is not enough. Maybe, deep down, all of us who have survived have had a feeling, if we told the story, the world would change, and the world hasn’t changed. Does it mean that we did not tell the story? Or not well enough? Simply, we did not find the words to tell the story? Had we told the story well enough, maybe it would have changed the world? It hasn’t changed the world.”

“Do you feel like you have failed in some measure there?”

“Not failed,” Wiesel replied quickly. “I didn’t say fail. Failing, if I had not tried. Look, I know I tried. I still try.”

Complementing his activism for human rights, Wiesel is a dedicated student of Talmud and has a deep appreciation of Chassidic and biblical stories, which the Independent referred to as “old” in asking a question about such stories’ relevance today.

“They are not only old, they are immortal,” said Wiesel. As to specific lessons we could learn, he added, “It depends what area. If it’s the Bible, then the eternal truth, or at least the eternal quest for truth. The Talmud, it’s my passion – I grew up with the Talmud and, to this day, every day, I study – I love it. I love study.”

Wiesel explained, “There is so much beauty in all that. There is so much….” He paused. “Truth is a difficult word because my truth may be mine, but not yours, but learning, the quest for truth, is extraordinary. For me to teach those texts is so rewarding, so rewarding. And we take a theme, a talmudic theme or a biblical theme or a prophetic theme, and it can go on, it can last for us for hours and hours and hours in class.

“Come on, the beauty of an Isaiah, the tragic sense of a Jeremiah, and the immortal dimension of a Habakkuk. It is all these. They survived. The very fact that they survived, you know, how did they survive? These are texts conceived, written and spoken 3,000 years ago or so, 2,500, and they survived. What made them survive?”

The concept of truth came up again when the Independent asked Wiesel’s opinion – as a former journalist himself – about how much a newspaper should reflect extremes within the community it serves.

“I gave up journalism. Do you know why?” asked Wiesel. “I liked journalism at the beginning; I loved it. It was to be at the nerve centre of history, come on, I loved it. Then I realized, what, two things. Number one, I repeated myself – which means I changed the names, but the words remained the same.” He paused, then continued, “I am going to spend my life like that? Second, I realized the people that I loved and admired; occasionally, they had such an attitude of fear and respect for the journalist – I said, I don’t want that, I don’t want to inspire that. That’s when I moved to the academic. I gave up, for that reason.”

Hesitant to give advice, Wiesel eventually said, “Young lady, your truth is truth. Listen to it. It’s your truth that matters. Don’t accept somebody else’s truth. And, if you are a journalist, if you have the respect for your own words, that will be read by hundreds or thousands of people, who will read it and maybe be influenced by it – you, just you, don’t listen to [anyone,] not even to your editors. Don’t tell them, don’t even listen to that,” he said, looking at Basya as he made the comment, and laughing. “You decide. When you publish an article under your byline, it’s yours.”

Despite having wondered aloud as to the effectiveness of his efforts to change the world, Wiesel still gets up every morning to do just that. “What is the alternative?” he asked rhetorically. “What is the alternative? There is no alternative. True, I fought many battles and lost. So what? I’ll continue fighting. Look, my life is not a life of success or victory, much more of failures. I tried so many things and failed, you have no idea. Of course, so what? I’ll continue. The only area where I feel I must continue is, first of all, education. Whatever must be done in Jewish life, and in life in general – not only for Jews – education must be a priority. Not the only one, but the main priority, education. Let’s surely aim for that. And then, Israel, to me, of course is – the centrality of Israel in my life is here,” he said, putting his hand over his heart.

A few moments later in the conversation, Wiesel returned to the topic of journalism.

“You know, as a journalist, my love would be to interview, not for news, [but] to have the interview. And that’s really what I loved about it, to meet people, to have real conversations, I mean, real dialogues – not questions and answers, because I know now about you more than you think, simply by the questions that you ask. But that’s the journalist in me.”

“So, you obviously have faith in human nature … and you like to know more about people?”

“I do,” he said, with hesitation. “In spite of. It’s not because of, but in spite of.”