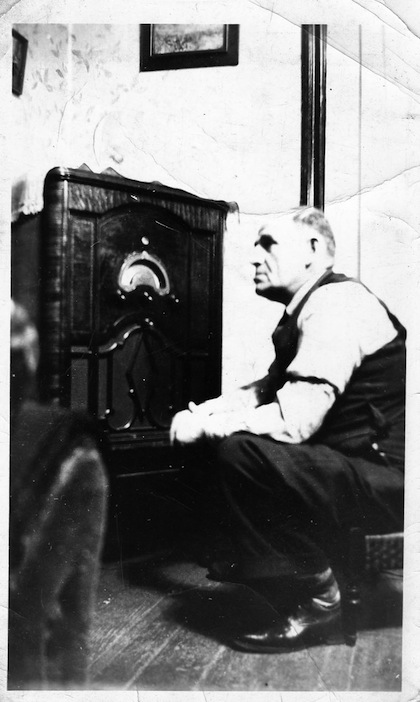

The writer’s father listening to the radio, circa 1940. (photo from Libby Simon)

This black-and-white picture, lined with age, was taken of Papa in about 1940. His attire reflects a time when a vest was commonly worn under a man’s suit jacket. It is rarely seen today, nor is the armband on his shirtsleeve. His white shirt makes the ensemble too formal to be worn at home, especially with his often-repaired dress shoes. But Papa was a Hebrew teacher and, perhaps uniquely to him, he always dressed as if he were going out. The bare, worn floor reveals a modest home, not uncommon in the 1930s, considering the widespread impacts of the Great Depression.

He sits in rapt attention, hunched on a stool, his expression tense, his eyes fixed on an old, brown, wooden floor radio. We grew up with that radio the way people grow up today with television. It connected our family with the outside world, but each for different reasons. As immigrants, Yiddish was our first language and, for him, radio undoubtedly served as an opportunity to hone his English, as well as to receive its messages. Although I was still a preschooler, I remember what he was listening to because the scene in this photo was repeated several times every day from 1939 to 1945, the years of the Second World War. Papa was listening to the news. But the true catastrophic human saga unfolding beyond the photo, even as he listened, would not emerge until after the war ended.

Fortunately, we here in Canada escaped the devastating fate of our relatives. As a child, I was only aware that certain foods were rationed, like tea, coffee, sugar and butter. My four brothers and I would fight over the krychik (Yiddish for the end piece of a rye bread). It was not the bread itself, but the limited availability of butter on the krychik that made this a special treat worthy enough to be fought over. If Papa were home, he would assign it to me as the youngest and as the only girl, much to the dismay of my brothers. But the rations coupon books provided by the Canadian government gradually extended to include many other staples, such as meat, cheese and evaporated milk. These were needed for the soldiers and the war effort.

I also remember short musical promotions appealing to Canadians to buy Victory Bonds. As a second-grader, I stood up in class one day and patriotically sang one such little ditty, which still reverberates in my memory. My substitution of the word “bun” for “bond” exposes my childhood ignorance that I only came to realize in retrospect as an adult. The lyrics go as follows:

“Buy a ‘bun’ V for Victory / Show you’re fond of your liberty / Keep on buying to keep them flying, / And don’t ever stop till they’re over the top.

“Every dollar makes Hitler holler / And every ‘bun’ you buy will make him groan / So help flood our Chest, / Do your best and invest / In Canada’s Victory Loan.

“Oh, Canada, we stand on guard for thee.”

The radio became such a central focus and source of news that, when the war ended in 1945, I wondered what would happen to it. “Papa,” I asked, “now that the war is over, will they close the radio?”

The radio became such a central focus and source of news that, when the war ended in 1945, I wondered what would happen to it. “Papa,” I asked, “now that the war is over, will they close the radio?”

“Why do you think they will close the radio?”

“Because,” I answered, “what else would they have to talk about?”

It was then I learned that radio not only delivered news about war. It also provided entertainment. For example, I discovered Hockey Night in Canada. My brothers and I would huddle around the radio every Saturday night and listen to Foster Hewitt, in his inimitable high-pitched excitement shout, “He shoots! He scores!” The contagion caused a clutch of five kids to holler in unison along with the sound of the roaring crowd – but only for the Toronto Maple Leafs. In time, I became a hockey aficionado, and could spout names like Syl Apps, Turk Broda or even Conn Smythe, their manager. Establishment of the Hot Stove League began during those early years and continues to this day.

We used to listen to shows like John & Judy, a serial about life in a small Canadian city, and Share the Wealth, with Bert Pearl. And Second World War songs filled the airwaves, like the “White Cliffs of Dover,” referring to the Battle of Britain. “We’ll Meet Again,” a song that resonated especially with soldiers off to battle and their families and sweethearts who had the heartbreak of waiting and not knowing if they would ever return.

Papa’s faded photo tells not only a personal story, but the story of many in Canada. It also highlights the role of radio in our lives. It served to bring the world into our homes between two catastrophic events – the Great Depression and the Second World War. We cannot overlook its importance as a medium of communication that brought the world into millions of living rooms across the country.

Of course, time brings change. My parents are long gone and my siblings and I have dispersed across North America. Radio was eventually muscled out by television but, today, you can “turn your radio on” in a resurgence of popularity. As a segment of mass media, the power of radio has infiltrated our lives again, even on the internet. And, online, you can go back to your childhood with “retro music” and shows like Roy Rogers and The Lone Ranger. It still connects us, though without taking up nearly as much floor space.

Libby Simon, MSW, worked in child welfare services prior to joining the Child Guidance Clinic in Winnipeg as a school social worker and parent educator for 20 years. Also a freelance writer, her writing has appeared in Canada, the United States, and internationally, in such outlets as Canadian Living, CBC, Winnipeg Free Press, PsychCentral and Cardus, a Canadian research and educational public policy think tank.