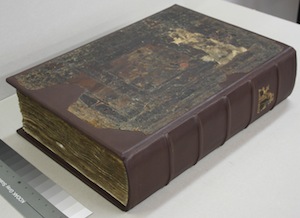

Pinkas Kehillat Frankfurt am Main contains records of the membership dues and other payments made by the members of the Frankfurt community between 1729 and 1739. It also contains copies of records from the 17th century. The pinkas contains 384 leaves and is written in German in Hebrew letters. (photo from National Library of Israel)

Many know that Shavuot, which we just marked, commemorates the receiving of the Ten Commandments. Less well appreciated, however, is that this holiday is the Jewish people’s beginning as the People of the Book. In this regard, it should come as no surprise that, within two weeks of Shavuot, throughout Israel, we celebrate Book Week, Shavuah Hasefer. But enough about new books.

Since the 1970s, in a tucked-away corner of the National Library of Israel, a small, skilled team conserves and restores the books and documents, not just of the Jewish people’s long and complicated heritage, but those of Muslims and Christians.

Timna Elper heads this department, which currently comprises four full-time and one part-time staff. Until I visited them, I did not understand how challenging it is to physically preserve a written legacy – archival materials face a battery of foes, such as fungus, insects and rodents.

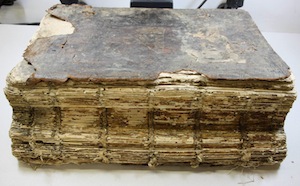

So, here is an admission: I naively believed the term bookworm just meant someone who loves to read books. While this does describe a certain kind of person, bookworms are actually an enemy of old books. Moreover, bookworms aren’t even worms – they’re the larvae of several species of beetles. And they have their preferences; that is, they generally leave newer books alone. If unchecked, they start their voracious dining on the spines of older books, moving on to feast on the pages. The sad result leaves books riddled with small holes and badly frayed covers and edges.

The repair work carried out in Elper’s department is, in a number of ways, similar to work done in hospitals. As in a medical facility, staff members must be highly trained in a number of fields. In the case of the library, we are talking about knowledge of fibres and textiles, entomology, chemistry, etc. To avoid contagion, sanitation is constantly checked: the library, for instance, closes during Passover and Sukkot in order to carry out fumigation of the entire facility. Tests are routinely carried out for fungal and insect damage. Temperature and humidity are monitored. Special care is taken to avoid stacking books too tightly, as this could endanger their physical stability when removed from their shelves. Attention is also paid to lighting (and not just sunlight), as improper or excessive lighting likewise harms books.

As for surgical procedures, library staff members carefully choose the materials for the restoration process, so that the book will accept, rather than reject, the repairs. The staff has to match the materials composing the old texts, be they parchment, animal skin or paper. However, no staff person is engaged as a scribe, as the department does not deal with restoring the text, no matter how faded or distorted it may be.

Along the way, the staff learns a lot about the old books. They learn about the community from which a text originated. They learn about the building of a book and what might have been involved in producing it. They explore questions that deal with the book’s content, as well as its cover. Was the book covered immediately or later in its life? Was the cover added where the book was written or was it put on in another country? And, if it was added in another country, what does this tell us about cooperation between historic Jewish communities?

Sometimes, to complete the restoration process and return the book for use, the staff employs specially developed machines, such as the Leafcaster, a machine that was developed by the department’s first director, Esther Alkalai. The Leafcaster helps strengthen a page by adding pulp to it.

Once the restoration is complete, the materials are available for study or for exhibition. To a degree, this action puts the texts at risk for contamination or physical damage. Thus, when the National Library loans rare items for temporary display, the restoration and conservation lab goes into full swing with a complicated process of ensuring the articles travel safely. The condition of the items is meticulously inventoried before they leave the library and when they are returned. In addition, a staff person from the lab accompanies the items in order to review the state of the pieces with the receiving institution and to help make sure that the loaned materials are being shown in a way that will not cause harm. When the exhibit closes, a staff person returns to the hosting facility to safely bring the valuable books and manuscripts back to the library. The library also makes special security and customs arrangements. An agreement is signed stating that the loaned articles will all be returned to Israel.

The restoration process is expensive, and the waiting list for repairing these treasures is in the thousands. While there are donors willing to underwrite the cost of digitizing archival material, few people are willing to contribute to the cost of the restoration.

Elper would love to have people adopt archival material, so that it could undergo restoration at the National Library of Israel. Such a program, she said, has been instituted at the British Library and other institutions. Reportedly, at the British Library, the funds raised through its Adopt a Book program have supported the conservation of thousands of items – books, manuscripts, maps, photographs, stamps and works of art on paper. The possibilities are numerous; one of Elper’s suggestions is to approach different ethnic communities or individuals to adopt or sponsor the repairs needed on an article from their community of origin.

Asked what was the library’s most difficult project to date, Elper said all projects have their challenges. While difficult was not her choice of word, she admitted that preparing for the arrival of a large external (out-of-the-library) archival collection required painstaking attention to removing any known contaminants and, stage-by-stage, safely transporting these acquisitions to the National Library’s archives.

Among the most satisfying projects for the team, Elper said when asked, was the preparation for the recent exhibit at New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, called Romance and Reason: Islamic Transformations of the Classical Past. The library lent the institute exquisitely scripted and illustrated manuscripts dealing with the story of Alexander the Great.

The repair of items (donated and purchased) creates a living testimony of history. It is the hope of the National Library of Israel that these rare and cherished books will receive even more attention when the library moves to its new facility in 2020.

As a closing note: if you have old books you love, keep them away from direct light and, to protect them from dust and other grime, store them in archival-quality, acid-free envelopes. Don’t do as yours truly had been doing, keeping them in various Ziploc bags. In closed plastic bags, the books have limited ability to breathe.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.