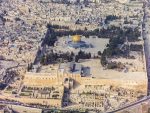

Jerusalem (photo by Andrew Shiva via Wikipedia)

Hospitality is culture itself and not simply one ethic amongst others. (Jacques Derrida, On Cosmopolitanism)

One of the late French-Jewish philosopher Jacques Derrida’s most famous short works is his On Cosmopolitanism, in which he discusses the problem of refugees. Cosmopolitanism is a word first coined in ancient Greece by wandering, homeless philosophers and popularized by the Stoics. It refers to the idea that the whole world (cosmos) is my city, or community (polis). It is the idea of an international or, better, transnational humanity and citizenship. Cosmopolitanism became popular again during the European enlightenment and slowly had a growing influence on international law and modern ethical sensibilities, including the sense that countries have a duty of hospitality, of offering refuge even to peoples of other nationalities.

This same ethical idea occurs in Derrida’s own Jewish tradition, where “love the stranger” is a commandment uttered many more times than “love your neighbour” and where Isaiah the prophet urged Israeli kings to give shelter to refugees of war.

In On Cosmopolitanism, which was based on a speech Derrida gave to the International Parliament of Writers on the subject of refugees, Derrida discusses the nature of hospitality and the contradiction at its heart. Hospitality involves welcoming guests into your home, in sharing resources and shelter, yet, to do so, it must remain “a home.” Should all boundaries of the home dissolve in unconditional welcome then the possibility of hospitality itself will also be obliterated. Derrida’s insight mitigates against a naive or utopian call for the obliteration of borders or the indiscriminate welcome of refugees.

In this thought of Derrida we see a tragic conflict at the heart of modern Zionism. Do we want a hospitable Zionism? Is the house the Jews built in Israel for Jews alone? Yet if the doors are flung wide, what will happen to “our Jewish home”?

There is much anxiety to protect our “home,” of that we can be sure. An extensive security wall, checkpoints, and airport border guards who are masters of interrogation. When we press Israel to become more hospitable – to African asylum seekers, to displaced Palestinians – we hear a chorus of voices arise: if we let them in, if we include them, the demographics will dissolve our home!

And we so badly want a home. Wandering for 2,000 years, we were homeless, exiled, a tolerated or cursed minority. Finally, we returned to our ancient home and, amid controversy with others who had come to live there and also claim it as home, built walls to protect it. We now again had a home, and we have chanted this word to ourselves over and over again, “home, home,” for the last 70 years.

Yet what good is a home that does not extend hospitality? Sure, we airlifted Ethiopians, we opened our arms to Russians, and so on and so forth. Yet they were us, our family. True hospitality, though, as it says in our own foundational text, is given to the stranger. The other.

Unconditional welcome is not the only way to destroy a home. What good is a home that offers no hospitality? Is a home that offers no hospitality even a home at all?

Israel is in the process of deporting the 60,000 African refugees who arrived before the building of a barrier wall with the Sinai to prevent more entering. As Russel Neiss wrote in the Forward, “For years, in actions held to be illegal multiple times by Israel’s Supreme Court, the Israeli government has arrested and placed these refugees in a detention centre in the Negev and forcefully deported them to other African nations in exchange for money or favourable terms for weapons contracts and military training.”

Twenty thousand refugees, most from Sudan and Eritrea, have already been deported or left of their own accord, and the government has ordered the rest to leave, with a small financial gift and plane tickets paid, or be jailed.

According to Derrida, hospitality is both a duty and a defining feature of a real home. The feeling that an inhospitable Israel is not really a home, I fear, is growing and will continue to grow among Israelis and Jews. Maintaining the feeling that Israel is a Jewish home only will require an unremitting focus on perceived and real threats to Jews in Israel and abroad. It will reinforce the unhealthy sense of home as a shelter from others, rather than fostering the healthy sense of home, one that is open to sheltering others.

The result may be that we have a very well guarded home. But, for those of us who perceive the lack of hospitality on offer, it begins to feel like no home at all. The opposite of Derrida’s formula – “in order for there to be hospitality, there must be a home” (a formula that is surely true and needs due respect) – is “in order for their to be a home, there must be hospitality.”

Jews, being a transnational people for so many years, became, in two senses, a “cosmopolitan people.” One was that fact of transnationality; the other stemmed from the involvement of Jews in socialist political movements, which problematized nationalism, as well as our involvement in activism aimed at the liberalization of immigration laws. It was all of this, seemingly, which coalesced to give birth to the use of “cosmopolitan” as an antisemitic code word for “Jew.”

I don’t think “cosmopolitan” is an insult, but rather a very high compliment. When an antisemite calls Jews “cosmopolitan,” I hear it as a calling, not a calling out. Israel will not truly be our Jewish home until it embodies the highest cosmopolitanism of the Jewish spirit, which can be read in the Torah’s call – millennia ago – to love the stranger and refugee.

Matthew Gindin is a freelance journalist, writer and lecturer. He writes regularly for the Forward and All That Is Interesting, and has been published in Religion Dispatches, Situate Magazine, Tikkun and elsewhere. He can be found on Medium and Twitter.