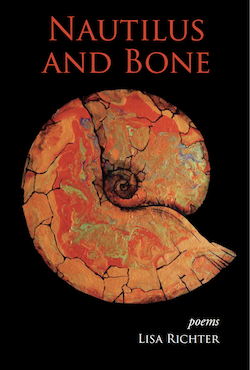

Lisa Richter, author of Nautilus and Bone, joins the Jewish Book Festival Feb. 7 (photo from Lisa Richter)

Nautilus and Bone: An Auto/biography in Poems by Toronto poet Lisa Richter – who takes part in the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival on Feb. 7 – will send readers down many proverbial rabbit holes. They will want to know more about the writings and life of Yiddish poet and journalist Anna Margolin – not only to better understand Margolin, but to appreciate more fully Richter’s poetic biography of Margolin and her conversations with Margolin’s works.

Margolin is the pen name of Rosa Lebensboym, who was born in Brisk (now Brest, Belarus) in 1887. She immigrated to New York City in 1906, “spent time in London, Paris, Warsaw, Odessa and Palestine before eventually settling permanently in New York in 1913, where she died, in 1952.”

Says Richter: “I was enticed by this Russian-Jewish-American woman writing a hundred years ago about myth-making, roots, identity, alienation, gender fluidity, Eros and desire (at times unmistakably queer, arguably pansexual). Her poetry felt bold and subversive, even by modern standards: H.D. meets Patti Smith.”

Richter does not speak Yiddish, so has relied on Shirley Kumove’s Drunk from the Bitter Truth: The Poems of Anna Margolin, a translation of Margolin’s volume of poems, Lider (Poems), with a “thorough and comprehensive introduction to Margolin’s life and work.” Richter also accessed Margolin’s files at YIVO and read Reuben Iceland’s (Ayzland’s) memoir, From Our Springtime: Literary Memoirs and Portraits of Yiddish New York, as well as other source material.

Richter discusses her many reasons for feeling connected to Margolin, including that, as Lebensboym adopted the name Margolin upon arrival in New York, Richter’s maternal great-grandfather, born Samuel Margolin, “changed his surname to the more Russian-sounding Lapitsky to avoid antisemitism when he immigrated to Montreal as a young man in 1903.”

Richter writes, “I like to imagine him meeting Miss Rosa Lebensboym. In my imagination, he passes his old birth name to her, much in the way one would pass along a string of heirloom pearls to one’s daughter (though they would have been roughly the same age, both born in the 1880s).” Richter notes that the name Margolin and its variations come from the Hebrew margoliyot, meaning pearls.

The emotional and spiritual connections come through in Nautilus and Bone. Richter does not claim to explore every facet of Margolin’s life and work. She explains, “The persona I have enacted in these poems hovers on the periphery of my imagination, filtered through my own dreams, preoccupations, (dis)pleasures, experience. I try my best to give a lyric voice to the most essential, enduring aspects of the poet’s life and work as I see her, and to engage in conversation with those parts of myself that are most closely, most symbiotically intertwined with her story.”

And she does so in a wide variety of poetic forms, all of which she wields with great skill. Among the recognition the book has garnered are the Canadian Jewish Literary Award for Poetry and the National Jewish Book Award for Poetry (United States) – “the first time a Canadian poet has ever received this honour,” Richter shared with the Independent.

In Nautilus and Bone, most readers will encounter forms of poetry they’ve never encountered before. “A City at the Sea’s Mouth” is a homolinguistic translation (in this case, English to English). “Primeval Murderess Night Talks Back to Anna Margolin” is a Golden Shovel poem – the “end-words of each line make up the first two lines of Anna Margolin’s poem ‘Primeval Murderess Night,’” notes Richter, crediting the creation of the form to Terrance Hayes. And, as the name suggests, “Anna Margolin Cento” is a cento, in which a poem is composed of lines from other poets’ poems.

“A poem’s form and content are inextricably linked, in the same way that a particular dish can only be made or served in certain kinds of containers,” Richter told the Independent in an email interview. “The same raw dough can be shaped into dinner rolls, pretzels or challah bread – the way you present and shape the material will affect the way it’s consumed and experienced.

“In some cases,” she said, “the form came to me later (the prose poem form of ‘So Uncommonly Smart for a Girl,’ for example) after a traditional, lineated form didn’t seem to be working. In other cases, the form came first, and the poems later. For instance, the long sequence of sonnets at the end of the book became the vehicle for telling the love story of Anna Margolin and her final life-partner, the poet Reuben Ayzland, as the sonnet has a long and distinguished history of wrestling with matters of the heart.

“The process of homolinguistic translation, or ‘re-translating’ a poem from the same language, is a means of engaging/wrestling/ conversing with a source text, and keeping it alive by breathing new life into it, using fresh grammar, syntax and language. I see it as an act of homage and tribute.”

Some of the poems were written as early as 2017, said Richter, shortly after her first book – Closer to Where We Began – was published, but “the bulk of the poems were written over the course of a year-and-a-half, from 2019 to spring 2020,” she said. “The original manuscript was much more autobiographical, but once I started researching and writing the Margolin poems, it became clear that the book was to become ‘an auto/biography in poems,’ as the book is subtitled, and was much more about Anna Margolin than it was about me. I have to credit my editor at Frontenac House, Micheline Maylor, for her vision and encouragement for this project. Both she and George Elliott Clarke, my mentor at the Sage Hill Spring Poetry Colloquium, were extremely supportive.”

Some of the poems were written as early as 2017, said Richter, shortly after her first book – Closer to Where We Began – was published, but “the bulk of the poems were written over the course of a year-and-a-half, from 2019 to spring 2020,” she said. “The original manuscript was much more autobiographical, but once I started researching and writing the Margolin poems, it became clear that the book was to become ‘an auto/biography in poems,’ as the book is subtitled, and was much more about Anna Margolin than it was about me. I have to credit my editor at Frontenac House, Micheline Maylor, for her vision and encouragement for this project. Both she and George Elliott Clarke, my mentor at the Sage Hill Spring Poetry Colloquium, were extremely supportive.”

While Richter’s conversations with Lebensboym/Margolin left her with more questions than answers, Richter said, “I think that’s a good state of mind for a poet to live in. As Rilke famously put it in Letters to a Young Poet, ‘Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now.’ I don’t think I’ll ever be entirely ‘done’ with Anna/Rosa, but it’s not entirely up to me. For all I know, she’ll be with me for some time…. I would love to learn to read Yiddish someday so I could read and appreciate her work in its original form.”

As for what she hopes readers take away from the conversations, Richter said, “Mystery, uncertainty, history, complexity, ambiguity, ancestral lineage, eros/sensuality, mythmaking. But if a reader just finds one poem in the book that speaks to them, I’m happy.”

Richter will be joined Feb. 7, 6 p.m., by local translator Rachel Mines (Jonah Rosenfeld: The Rivals and Other Stories; see jewishindependent.ca/stories-that-explore-the-mind) in a discussion with moderator Faith Jones. Visit jccgv.com/jewish-book-festival.