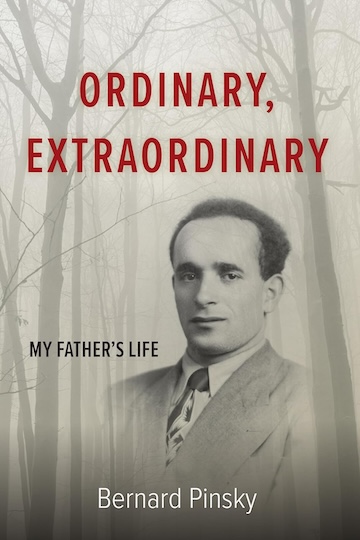

In his ambiguously titled book Ordinary, Extraordinary: My Father’s Life, Vancouver lawyer and community leader Bernard Pinsky shares the biography of Rubin Pinsky. As the pages turn, the reader realizes that ordinariness and extraordinariness really do describe the tale of a life that veers from historically monumental to surprisingly, and gratefully, commonplace.

At 1 p.m., Jan. 28, Pinsky will officially launch the book, in honour of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, at a prologue event to the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival. He will present in conversation with Marsha Lederman.

At 1 p.m., Jan. 28, Pinsky will officially launch the book, in honour of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, at a prologue event to the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival. He will present in conversation with Marsha Lederman.

Pinsky’s book is based on videotaped testimonies that his father, Rubin, gave in 1983 and 1990 to the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre (which is co-presenting the Jan. 28 event), as well as family memories and what is clearly intensive research.

Rubin was born (probably) in 1924, about 100 kilometres north of Pinsk in what is now Belarus but was then Poland. Pinsky sets the stage beautifully, evoking shtetl life, where the smallest of the children slept atop the bakery oven in the tiny home after his father, Baruch, had baked challah and cakes during the day to eke out a meagre living.

After the German occupation, the Nazis quickly identified the men in the Jewish community who had leadership qualities and said they were needed for an important mission in a nearby area. They were marched just out of earshot and mass murdered. In a later selection, Baruch, his wife Henya and 10-year-old Rachel were marched off and never seen again.

Rubin and his sister Chasia were deemed useful for forced labour and spared the executions. Older brother Herzl had earlier been conscripted into the Red Army.

Every survivor narrative includes a series of unimaginable interventions, coincidences and happenstances, often made possible by acts of incredible daring by the survivor. Through a series of audacious escapades – they weighed off what appeared to be likelihood of certain death with the faint hope of survival – Rubin, Chasia and a few others escaped a selection process and fled to the forest. They lived off berries, roots, tree bark and what small game they could capture. In one instance, Rubin slew a timber wolf in a competition for the same rabbit.

The group connected with a diffuse but apparently well-organized network of Jewish and other partisan fighters. Despite the challenges of mere survival, Rubin and Chasia participated in anti-Nazi actions that included cutting telephone lines, destroying railway tracks and undermining the establishment of Nazi garrisons.

Typhus swept through the Jews in the forest. In the winter of 1943/44, Rubin was delirious with fever and expected to die. In one of the terrible choices people were forced to make in such situations, the partisan cadre decided to leave him behind to save the group. Chasia refused to go. The two siblings hid in a ditch and, to the best of her ability, she nursed him back to comparative health.

Each of these unlikely survival stories makes one wonder how many similar stories did not have the relatively happy ending Rubin’s did, how many survivor testimonies or second generation narratives were never written because the fever did not break, or the hero did not take a risk on a faint hope, or any of a million chance escapes or saving miracles did not occur in time.

In July 1944, the forest in which Rubin and Chasia had hid, fought and barely survived was liberated by the Soviet army. Concentration and death camps were repurposed into displaced persons camps after the war and Rubin and Chasia were in Bergen-Belsen. Chasia left and searched for three weeks, eventually finding Herzl and bringing him with her to Bergen-Belsen, where the three surviving members of the family were reunited.

Zionists tried to recruit them to go to Palestine, but Rubin knew that would be a continuation of the conflict, uncertainty and fighting he wanted to put behind him.

“Rubin therefore made up his mind,” writes Pinsky. “He needed a skill or trade in demand in America. He and Herzl made a pact. They would study together, each in a different trade, and go together to the New World. They would help each other and never be separated again.”

The story of how Rubin and Herzl (in the New World, he would be known as Harry) were able to migrate to Canada is another example of chutzpah – an hilarious drama of subterfuge – that has to be read to be believed. Chasia, whose marriage in the DP camp did not last, joined them soon after.

Rubin married Jenny Moser in 1951 and they would have three children: the author, Bernard, his older sister Helen and younger brother Max – all now mainstays of the Vancouver Jewish community. Rubin’s life in Canada was that of a hardscrabble entrepreneur – and not without its seemingly miraculous near-misses and fortunate endings.

As an appendix, Pinsky shares writings from a 2012 family roots trip back to Gzetl, where a dedicated teacher is keeping alive the memory of Gzetl’s Jews.

Pinsky’s memoir is indeed a story both extraordinary and ordinary, of what human resilience can summon in a world turned upside-down – and how the strength developed in unimaginable adversity can carry a survivor through challenges when life becomes, in comparison, ordinary.

Register for the event at jccgv.com/jewish-book-festival/events.