Cambie Street, looking south from 41st Avenue, 1952. (photo from City of Vancouver Archives via jewishmuseum.ca/oakridge)

On Nov. 23, the Jewish Museum and Archives of British Columbia had both its annual general meeting and launched its newest online exhibit, Oakridge.

JMABC board president Perry Seidelman called the AGM to order and noted a major absence.

“Forty-five years ago,” he said, “Cyril Leonoff became our founding president and was at our side throughout all of those years. However, sadly, this ongoing support ended this year with Cyril’s passing. There is so much that can be said about Cyril but tonight I will only say that he has been and will continue to be missed. It goes without saying that we would probably not be here tonight if it was not for Cyril Leonoff.”

Seidelman then went on to list some of the year’s accomplishments, including ongoing speaking engagements and historical tours, as well as the recording of 35 new oral history interviews and the digitization of “various family fonds, the Mountain View Cemetery Restoration Committee fonds and the Temple Sholom fonds.”

He noted that the digitization of “the oldest books from Congregation Emanu-El (1861 through 1901 approximately)” was complete and they will be online soon, that several online exhibits had been mounted during the year, and that the museum’s “largest collection by far, the Canadian Jewish Congress, Pacific Region, fonds, has begun to be processed, with immense research potential.”

The museum handled hundreds of research requests, he said, and “received donations ranging from fiction manuscripts to synagogue records to WWII records.”

Seidelman noted that longstanding JMABC member (and a past president) Bill Gruenthal was recognized by “Jewish Seniors Alliance for years of extraordinary volunteer work” and that archivist Alysa Routtenberg had “recently completed her first year as archivist as Jennifer Yuhasz’s successor. It has proven to be a nearly seamless transition with a continuing and increasing inflow of documents and interviews and regular transmission of the vast history of which we are guardians.”

He thanked JMABC administrator Marcy Babins, JMABC coordinator of programs and development Michael Schwartz, Shirley Barnett for her leadership in the restoration of the Jewish section of Mountain View Cemetery, Cynthia Ramsay for editing the JMABC’s annual journal, The Scribe, and donors and funders, including the Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver. He bid farewell to three members of the board – Barnett, Chris Friedrichs and Barbara Pelman – and welcomed four new members: David Bogoch, Alan Farber, Alex Farber and Carol Herbert.

After the AGM was the Oakridge launch.

“With this exhibit,” said Schwartz, “we set out to document an important period in our community history; a moment when a population boom coincided with financial stability and postwar optimism to cause our community to grow both in size and stability in a way rarely seen before or since. This era set a new foundation for our community that we have built upon and relied upon ever since.

“This exhibit places this period in context with events happening both before and since. It asks why and how many Jewish families and institutions chose to establish themselves in Oakridge.”

Compiled over two years, the Oakridge research team was Erika Balcombe, Junie Chow, Elana Freedman and Josh Friedman, with Schwartz. A large portion of the exhibit comprises oral history interview excerpts from community members Harry Caine, Vivian Claman, Irene and Mort Dodek, Gail Dodek Wenner, Wendy Fouks, Debby Freiman, Sarah Jarvis, Ed Lewin, Sandy Rogen, Ken Sanders, and Seidelman.

“Irene deserves double thanks,” said Schwartz, “as we have included an excerpt of an interview that she carried out with Bea Goldberg and Marjorie Groberman in 1996. Naturally, I thank Bea and would certainly thank Marjorie were she still with us.”

Schwartz also gave thanks to JMABC colleagues Babins and Routtenberg, as well as Yuhasz, “each of whom devoted much time and energy to this project,” and the board of directors.

At the turn of the last century, explained Schwartz, “there were essentially two interconnected Jewish communities: the affluent Reform Jews in the West End and the Orthodox, working-class Jews in the East End, what today we call Strathcona…. Over time, the Jews of the East End grew more financially stable and began to relocate to the new neighborhood of Fairview in the 1920s and ’30s.”

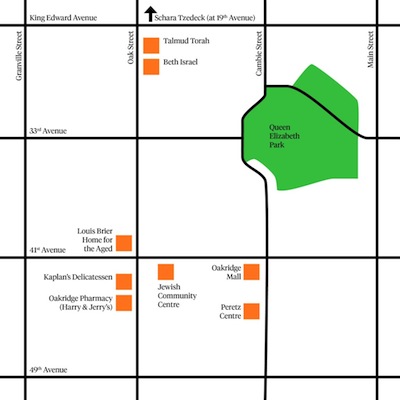

He noted, “If the Great Depression hadn’t hit, it seems likely that Oak and 12th Avenue would have been the heart of the Vancouver Jewish community. Instead, campaigns to build Beth Israel, Talmud Torah and a new Schara Tzedeck were put on hold until after the war. All three projects were completed in 1948. By that time, the city had continued to expand southward, so these three facilities were built closer to King Edward Avenue.

“This southward shift was further encouraged by another important event,” he continued. “In 1950, the CPR, the Canadian Pacific Railway, released a parcel of land stretching from 41st Avenue and Granville Street to 57th Avenue and Main Street. The city identified the middle third of this land for residential development and worked with Woodward’s and other developers to construct Oakridge Mall as an anchor for the new neighborhood.

“This neighborhood didn’t attract exclusively Jews, but it arrived at a perfect moment for our community.”

There was a lot of material from which the researchers had to choose. “The work was to pare it down to a manageable size, a representative cross-section of the community,” said Schwartz. “As you can imagine, everyone we spoke to had a very different experience. For instance, Vivian Claman and Ed Lewin shared with us the experience of survivor families.”

In the exhibit, said Schwartz, Lewin comments, “The survivors and their children were almost like a sub-community of the Jewish community. We kind of did everything together, we were like an extended family.”

“In general, the Baby Boomers we spoke to had happy memories of their childhoods,” said Schwartz, giving the example of Claman.

“We played in the street – we would be gone all day,” she says in the exhibit. “We played kick the can! I mean, those were the days that you would go outside and you would just play till it was dark or till your parents yelled and said come in for dinner. There was a lot of hanging out.”

That’s not to say everything was perfect. Schwartz noted Mort Dodek’s comments in the exhibit.

“One other thing that you have to understand is that there was a lot of antisemitism at that time,” says Dodek. “There were people who were uncomfortable living in Shaughnessy, a lot of Jewish people were not comfortable there. The Shaughnessy Golf Course was there, and it was restricted, no Jews were allowed to join that club.”

And Irene Dodek notes, “When we first moved to Vancouver in 1947, my parents went out with a real estate man to look at a house at 25th between Oak and Granville, and the real estate agent told my father, ‘This is a good neighborhood because no Jews or Chinese are allowed.’”

Schwartz also pointed out that there were divisions within the Jewish community, citing Seidelman and Mort Dodek’s comments from the exhibit.

“The rabbi of Schara Tzedeck would not go to Beth Israel, would not be seen to enter, whereas today they have the Rabbinical Association, all the rabbis get on really well together and they seem to respect each other’s different levels of observance, whereas in those days they didn’t,” says Seidelman.

“If you want to talk about splits in the community,” says Dodek, “there was a terrific split between the people who were involved with the Peretz shul and people who were involved with, say, Talmud Torah…. It was not religious and believed that the main language to speak for a Jewish person was Yiddish. And, of course, the people at the Talmud Torah, the language to speak, of course, with the establishment of the state of Israel, was Hebrew.”

“Another theme that emerged through our interviews,” said Schwartz, “was the way gender roles were changing and have changed since the 1960s. Men always worked outside the home, but women rarely did. This was beginning to change, but very slowly. Without full-time jobs, women had the time to dedicate to volunteer organizations like Hadassah and National Council of Jewish Women. Both organizations accomplished a great deal in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, but have struggled in the years since, as fewer young women have the time to devote to this type of work.”

For anyone wanting to know more about the role of women in the community, Schwartz recommended the museum’s 2013 exhibit More Than Just Mrs., which can be found online.

“Oakridge, like each of our exhibits, serves three functions,” said Schwartz, listing those functions: a chance to grow the museum’s archives, to increase awareness of the JMABC and of Jewish life in the province, and to reflect on how the community has changed over time.

For the Oakridge exhibit, he noted, the majority of the oral history interviews “were undertaken by volunteer and student interns, giving them valuable experience in the art and science of oral history interviews. Thanks to projects like this, including other exhibits and our annual journal, The Scribe, our oral history collection has grown substantially in recent years, bringing our current total to 762 interviews.

“Just this month,” he added, “we held two interviewer training sessions as the first phase of our Southern African Diaspora Oral History Project…. Through this project, we intend to interview hundreds of community members who arrived here from South Africa and the neighboring countries in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s.”

With respect to increasing awareness, Schwartz said, “Many of you will remember the launch of our modern architecture exhibit New Ways of Living back in January of this year. This event had an attendance of over 150 people, many of whom were not Jewish and found out about the event through our partners, Inform Interiors and the UBC School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Similarly, our 2015 exhibit, Fred Schiffer: Lives in Photos, attracted more than 800 people over its two-week run, again with much thanks to our partners, Make Gallery and Capture Photography Festival…. Each new exhibit has a specific thematic focus which draws in a new audience.”

As for reflection on the Oakridge years, Schwartz pointed to the expansion of the Jewish community. “Families,” he said, “have settled into neighborhoods throughout the city and the region in general.”

Referring to the Oakridge area, he concluded, “[I]f fewer and fewer Jews live in this neighborhood, does it make sense for the Oak Street corridor to remain the hub of much Jewish activity? This remains to be seen.”

See the exhibit at jewishmuseum.ca/oakridge.