Lilian Broca with the diptych “Judith Meeting Holofernes,” part of the Heroine of a Thousand Pieces: The Judith Mosaics of Lilian Broca exhibit that opens at Il Museo on Nov. 12. (photo from Lilian Broca)

Artist Lilian Broca calls her most recent subject – the apocryphal Judith, who slew the general Holofernes and saved her village – “a woman’s woman,” because “she was able to do what she wanted to do.” Granted, times have changed, and that’s not such an unusual phenomenon, but equality is still an issue for many, there are still oppressors, the world is still in need of repair, tikkun olam. Broca’s work reminds us of the power we each have, woman or man, to save, heal or improve at least a part of the world in which we live. And it does so in the most beautiful way.

Heroine of a Thousand Pieces: The Judith Mosaics of Lilian Broca opens at the Italian Cultural Centre’s Il Museo on Nov. 12, 7 p.m., with a reception. It is the artist’s second major mosaic series. Her first – seven years in the making – told the story of Queen Esther, the heroine of Purim.

“Throughout my career,” writes Broca in the Judith exhibit catalogue, “I have deliberately used powerful women figures from mythology as symbolic figures and role models whose experiences, I contend, shed light on today’s concerns, thereby becoming relevant to our contemporary society. In my last three series of artworks, I have profiled three exceptionally wise and fearless legendary figures: Lilith, Esther and now Judith.”

Over the years, she has worked with a variety of media, but the Queen Esther series called for a new medium: “In the Book of Esther, it is written that King Xerxes’ palace was magnificently adorned with a floor encrusted with rubies and porphyry in pleasing designs – in other words, mosaics.”

As with the Esther series, the nine panels depicting seven scenes from the story of Judith are created in Italian smalto glass. The panels range from 72 to 78 inches tall and 48 inches wide.

As a widow with no children or family, Judith was able “to act on her own without getting permission from the alpha male of her family,” Broca told the Independent. That allowed her to do what she did, “because women, as you know, in biblical times belonged to a male, either a husband, father, brother, son. She had none of those, and she was wealthy because her husband had left her quite wealthy. So, she was a woman’s woman, she was able to do what she wanted to do.”

In short, Judith wanted to save her village of Bethulia from the Assyrian army, which was under the command of General Holofernes, who answered to the ruler Nebuchadnezzar. A beautiful woman, she seduces her way into Holofernes’ camp and, eventually, into his tent, where she manages to get him so drunk that he passes out. She then cuts off his head with a sword, smuggling it out of the camp with the help of her servant. She presents it to the people of her village, while Holofernes’ army flees in disarray.

“We meet her at the point where she calls the town officials, and tells them that she’s going to be victorious,” and that she’s going to be successful with the help of God, explained Broca of the exhibit’s first panel. Judith doesn’t, however, tell them what she’s going to do.

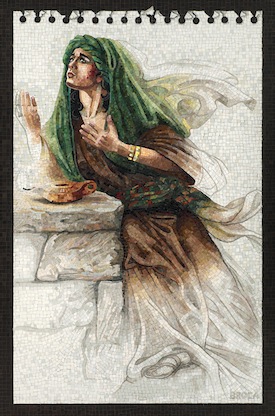

In the second panel, Judith is praying, asking God to help her deceive Holofernes and his men. Not knowing how women prayed at the time, Broca contacted Dr. Adolfo Roitman, curator of the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum (where the Dead Sea Scrolls are housed), but, despite his and other biblical specialists’ efforts, they weren’t able to answer that question. “So, I was left with my artistic licence,” said Broca. “I figured that light is always associated with the divine, and so I had a lot of photos of oil lamps dating from that century … and I decided to have her praying in front of that lit oil lamp, with that light, and her hands … she is begging God, she is arguing with God, she is having a dialogue, so I put her hands in a kind of gesticulating [position], up in the air.”

The third scene – one of the exhibit’s two diptychs – depicts Holofernes first meeting Judith in all her finery and beauty. “Judith, just like Esther, was articulate, spoke very well, and perhaps also God helped her,” said Broca. “She told the general a cockamamie story about God coming to her in her dreams and saying to her, you have to go down [to see him] because he will be the winner of the war, he’s a great leader, and I’m going to punish the people of Bethulia … because they broke the dietary laws. Well, that was true: they were starving, they had no water. The general knew that the Israelites had a very powerful God” who would protect them if they were faithful to Him and kept His laws. Judith continued, said Broca, “saying that God will tell her in three days’ time when is a good time to attack. During those three days, she will stay with him in the camp but, every night, she will go with her maid … to pray, and then come back to the camp. And then, on the third night, God will tell her. In the meantime, the general wanted to seduce her, that’s all he had on his brain.”

In this way, the sentry was used to seeing Judith coming and going, said Broca, which is why she was ultimately able to steal the severed head, hidden in a sack, out of the camp. The fourth scene of the exhibit is a diptych of Judith plying Holofernes with wine, the fifth panel shows Judith about to bring down the sword onto his neck, while the sixth has Judith and her maid running to Bethulia, sack and sword in hand. The final panel shows Judith raising the head for her people to see.

Broca started this work about four years ago. Roitman was in Vancouver giving a talk on the Dead Sea Scrolls and visited her studio. “When he saw Esther, he said, oh, now you have to do Judith.” He told her that Judith was likely written as a response to Esther, that Judith is the flipside of Esther. “And it is absolutely true,” said Broca. “When I read the story, I knew right then and there that my greatest dream in life is to have both Esther and Judith exhibited in one very large museum.”

Because they are completely different personalities, Broca used different methods in creating the two mosaic series. “Esther was executed in a Byzantine style, and that was because

Esther was a quiet, loyal little girl who manipulated men to do a dirty job, basically…. Judith, on the other hand, was a warrior from the get go.” Judith acted independently and “in a manly manner,” while Esther “acted within the accepted nature of women’s role in life,” said Broca. This is why the artist couldn’t create

Judith using “that very quiet, icon-like Byzantine style…. I had to use a more Baroque style to show her personality.” Judith’s depictions needed to have more action and movement, as well as more emotional facial expression.

Broca said that what attracted her to the stories of Judith and Esther, true or not, was that “these heroines illuminate the fundamental truth … and that is that one single individual, not just a group, male or female, can – and will – make a difference in a threatened community. Today, we have Malala [Yousafzai] – she is an example of such a heroine. And both Esther and Judith save their communities from being exterminated, or taken into slavery, as was the case with Judith, I believe.”

Both Esther and Judith are examples of women’s empowerment, and can serve as role models, said Broca. As well, the medium of mosaics bears its own message, not only connecting an ancient art with contemporary times, the past with the present, but also in that “our world is becoming more and more fragmented, and it’s essential that all these fractured elements should be put together in order to heal, to make the world whole once again.”

In the Esther series, the unifying motif that ran through the panels was a wrought-iron lattice that appeared in each one. Broca said she agonized for weeks over what would be the unifying motif in the Judith series. “Finally, I came up with this idea of a torn sketchbook page. The reason for that is because I thought, well, what am I doing? I’m revivifying or reenacting an ancient story, and I’m starting from scratch, and it’s from my personal vision.” Since she started with sketches that became the mosaics, she thought, “Why don’t I show the whole process?” The sketchbook also becomes a “21st-century prop,” something that brings the work, and the ancient story it tells, into the present. Included in the exhibit are Broca’s sketches and painted sketches (which are called cartoons). “In total,” she said, “there will be 14 pieces under glass accompanying the mosaics.”

The catalogue accompanying the Judith exhibit is comprehensive. It is a full-color, 94-page publication with essays by Broca and Roitman, as well as by Dr. Sheila Campbell, archeologist, art historian, curator and professor emerita of the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies; Dr. Angela Clarke, museum curator at the Italian Cultural Centre in Vancouver; and Rabbi Dr. Yosef Wosk, adjunct professor and Shadbolt Fellow in the humanities department at Simon Fraser University. The book’s foreword is written by Rosa Graci, curator at Joseph D. Carrier Art Gallery in Toronto, where the Judith series will be displayed from May 5-July 4, 2016.

The exhibit will be in Vancouver at Il Museo, 3075 Slocan St., until March 31, 2016. For hours and other information, visit italianculturalcentre.ca/events/museum. For more on Broca, visit lilianbroca.com. As well, three relevant stories are “Contemporary ancient art,” Nov. 18, 2011; “Piecing together a heroine,” March 21, 2008; and “Mosaics honor heroine,” April 30, 2004.