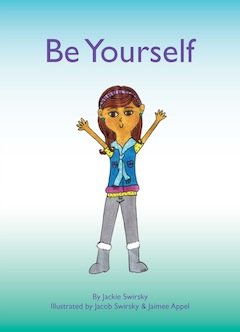

The Swirsky family. Jackie Swirsky has written a children’s book, Be Yourself, which features illustrations by her eldest child, Jacob, and her sister-in-law. (photo from Jackie Swirsky)

Maybe it’s because I’m an academic, but I tend to gravitate to categories, which is why the most current discourse on gender has made me feel challenged. I am, by now, very comfortable with the increasingly understood categories of transgender and cisgender (meaning that one’s body conforms to one’s gender identity). But what about cases of individuals who identify as neither transgender nor cisgender, but operate, instead, somewhere in the middle?

Jackie Swirsky, a speech-language pathologist based in Winnipeg, is the mother of two sons, one of whom (Jacob, age 8) Swirsky describes as “gender creative.”

Swirsky is my second cousin, but we only became acquainted after she published her children’s book, Be Yourself, which features a gender creative child and focuses on acceptance. We recently spoke by phone, where I admired her eloquence and compassion and, above all, her comfort with accepting the in-between.

When Jacob was 4, he said to his parents he felt it “wasn’t fair” that he was “a boy.” That’s when we opened up a dialogue, Swirsky said. Currently, he still identifies as a boy, “but his gender expression is very feminine,” she said.

There may have been a time when, faced with a son who prefers to dress in what are conventionally thought of as “girls” clothes, a parent may have tried to force the child to change. One can imagine the emotional pain that would have enveloped those households in those generations. Instead, Swirsky puts it plainly: Jacob “is perfect the way he is.” She sees it as her job not to change her child, but rather to “educate the world” in order to “make it a happier, safer place.”

Enter her book, Be Yourself, with illustrations by Jacob and Swirsky’s sister-in-law Jaimee Appel. It can be purchased at beyourselfbook.ca.

Enter her book, Be Yourself, with illustrations by Jacob and Swirsky’s sister-in-law Jaimee Appel. It can be purchased at beyourselfbook.ca.

Swirsky took her message to Camp Massad at Winnipeg Beach before camp started, as Jacob would be a camper there over the summer. Leading a workshop for counselors on how to rethink gender norms, Swirsky’s goal was to help the staff “identify their own gender stereotypes,” while encouraging them to open a dialogue with the campers – rather than scold – if they happen to encounter issues of gender stereotyping or instances of gender mocking.

And, while some camps might think of themselves as progressive on the issue of gender, given the easy availability of costumes and the playful gender-crossing that may ensue, Swirsky is clear: for Jacob, this isn’t “dress up,” it’s who he is.

Camp Massad program director Sari Waldman shared with me that, in trying to make camp as “inclusive and accessible as possible,” they are rethinking some of what they realize are overly gender-binary practices. “Simple things,” Waldman said, like do we really need to divide the chadar ochel (dining hall) along gender lines?”

They are now more sensitive to gender stereotypes when writing cabin songs. Not every boy plays sports and longs to sneak into girls’ cabins, they now realize. Waldman added that they have installed gender-neutral washrooms in various spots around camp, and would include a gender-neutral stall in the refurbished bathrooms. This year, for the first time, boys’ and girls’ cabins would no longer be on opposite sides of the field.

Other camps have taken gender-awareness on board, too. As was reported in the Washington Post, Habonim Dror camps across North America, including Camp Miriam on Gabriola Island, have created a new, gender-neutral Hebrew word for camper (chanichol) for those who identify as neither male (chanich) or female (chanicha). And they have renamed each of their age-group names with a pan-gender neologism suffix (imot) rather than the male im or the female ot. It’s a mouthful (and not traditionally grammatical), but the move has created new awareness around gender identity and the categories into which we put each other.

No doubt, attending Jewish camp won’t be without its challenges for someone like Jacob. It’s hard to get around separate sleeping and showering arrangements, even if privacy is granted for changing. And, when it comes to ritual garb, Jacob doesn’t feel comfortable wearing a kippah, for example. Swirsky hoped that the staff would either let him choose whether or not to wear one, or else ask everyone – boys and girls – to cover their head.

As for school, Swirsky finds that the teachers at her son’s school are excellent in supporting Jacob where he is. She also has much praise for the Winnipeg One School Division, which recently issued a new “safe and caring policy on transgender and gender-diverse students.”

Occasionally, though, there are setbacks. One day, a substitute teacher asked the kids to divide up according to gender. Relaying the day’s events to Swirsky that evening, Jacob revealed that he didn’t know which side to stand on. “I just sort of wandered,” he said.

While Swirsky finds that some people she encounters lavish praise on her for her apparent open-mindedness, she insisted that this is basic to who she is as a parent.

“I love and accept my child for who they are; not who I expect them to be,” she said.

And, when talking with Jacob, Swirsky always makes sure to ask open-ended questions. “If you’re really listening to your kid,” Swirsky said, “you’re going to help support them to be on a path that makes them happy.”

It’s a wonderful message about love and acceptance, parenting our kids where they are, and helping society evolve to embrace diversity – even if that diversity is much more finely grained than we may have realized.

Mira Sucharov is an associate professor of political science at Carleton University. She is a columnist for Canadian Jewish News and contributes to Haaretz and the Jewish Daily Forward, among other publications.