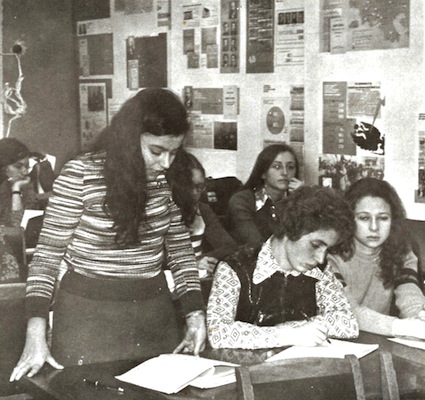

Left to right, Lilia Apelbaum, Olga Livshin and Tanya Kogan, during their reunion in Vancouver. (photo by Tanya Kogan)

For two weeks this August, my apartment was unusually crowded. Friends from Haifa and Los Angeles were staying with me. We talked almost nonstop the entire time they were here. While they have already left for their respective homes, the memory of their presence still lingers in my house, in the photographs and in my fond recollections.

In 1973, the three of us, three Jewish girls, high school graduates from different Moscow schools, lived in the Soviet Union. We met for the first time when we enrolled in the Moscow Institute of Economics and Statistics. For five student years, we were inseparable. We studied in the same groups and partied with the same friends but, after graduation in 1978, we parted ways. This year, 39 years later, the three of us met for the first time since then, at my place in Vancouver.

Many things have changed in our lives, of course, but, despite the grown-up children, deteriorating health and multiple wrinkles, all three of us have stayed basically the same: the same personalities, the same interpersonal dynamics, the same feeling of closeness as friends. And our relationship with our Jewishness also has stayed basically the same.

At the time of our youth, all observance of Jewish traditions in the Soviet Union was suppressed. Not banned, per se, but not encouraged. There was one synagogue in Moscow and, I have to admit, I never visited it. My parents tried to blend in with mainstream society, so they never visited it either. We didn’t celebrate Jewish holidays, and I didn’t even know about most of them. Only my grandfather went to synagogue on most Saturdays and some Jewish holidays. He tried to instil some sense of Jewish identity in our household (as he lived with us) but, unsupported by my parents, he was unsuccessful. I was never interested in anything Jewish when I was young.

The situation was a bit different with my two friends. Tanya Kogan (née Schneiderman) lived in a similar household to mine. Her parents’ one ardent desire was to blend in. Being “the same,” not sticking out, was safer in Communist Russia but, after her high school graduation, Tanya broke away from the “blend-in” mold.

“I wanted to know who I was,” she told me. She immersed herself not only in her academic studies at the institute but also in Jewish customs and traditions, to the extent they existed in Moscow of that time.

“I tried to learn Yiddish from my grandmother, even though she was ashamed to speak it. I went to synagogue for some Jewish holidays and, every year, for Simchat Torah. It’s such a fun holiday. Lots of students from our institute were there. Not many colleges and universities in Russia accepted Jewish students, but ours did, and there were many of us. We danced in the streets together,” she remembered. “I bought matzos every year and fasted on Yom Kippur.”

My other visiting friend, Lilia Apelbaum, was also part of the group of students that danced in the streets outside the Moscow synagogue on Simchat Torah. Her father came from a family where tradition was paramount.

“We bought matzos every year when I was a schoolgirl,” Lilia said. “We would travel on the Moscow Metro with the big packs of matzos wrapped in brown paper, to a seder in some relative’s home, and I would think: ‘I’m special. I’m better than all the people around me. I know something they don’t.’ I felt very proud.”

In 1996, Lilia, her parents and her young son immigrated to Israel. She still lives there, in Haifa.

“My father went to synagogue often when we lived in Moscow, but he stopped going after we immigrated,” said Lilia. “In Moscow, he needed it to prop his Jewish identity but, after we settled in Israel, he said he didn’t need it anymore. He felt Jewish and happy without the support of religion.”

Lilia herself doesn’t follow any Jewish tradition, doesn’t keep kosher and doesn’t attend synagogue, but she is still, as in her childhood, intensely proud to be a Jew and an Israeli. “I love Israel,” she said. “It’s a wonderful country, very humane.”

She told me a story about her neighbour and friend. “She is very sick. Once, we walked outside together, and she fell. Her legs wouldn’t support her and I couldn’t help her – she is a big woman, much bigger than myself. I panicked; didn’t know what to do. Suddenly, a couple cars passing along the street stopped. Totally unknown men climbed out of those cars, lifted her, helped her to a bench, and then drove away. Where else would a car stop just to help a strange woman on the sidewalk? Only in Israel.”

She talked about the urban improvements being undertaken in Haifa, about Israeli healthcare and technology, about her fellow Israelis, and her eyes shined with love for her country.

Tanya also left Russia. In 1996, she and her family immigrated to America and settled in Los Angeles. “I almost never go to a synagogue here,” she said. “But I do keep kosher. Mostly. In my own way. During Passover, we don’t eat bread. I make so many interesting dishes with matzos, my family always anticipates the holiday. They don’t want bread – they remember that torte and this pie for years after and always ask if I would make them again. It’s a game we play. It’s easy and fun to be a Jew in America.”

Like my friends, I left Russia, too, at about the same time. In 1994, I came to Vancouver. Unlike my friends, though, I didn’t get in touch with my Jewish roots right away. It took me some time to become a part of the Vancouver Jewish community. At first, I was busy with my computer programmer job, raising children as a single mother, and generally integrating into the Canadian society. But life has a wicked sense of humour. It pushed me toward my Jewishness in a roundabout way.

In 2002, I got very sick. My illness altered my worldview and induced me to change my priorities. In 2003, I started writing fiction. A few years later, I quit my computer job to dedicate myself fully to my writing career. At that time, I tried to find a writing gig. I took a course on a mentored job search, and one of the assignments was to find a mentor.

I scoured the internet for some Vancouver writing professional to approach, to ask to be my mentor, and came up with the name Katharine Hamer. At that time, she was the editor of the Jewish Independent, a newspaper I had never heard about before. I sent her an email and, to my amazement, she replied. She said she didn’t have time to mentor me, but she offered to add my name to the list of her newspaper contributors. I grabbed the opportunity.

My first article for the Jewish Independent was published 10 years ago, in July 2007. I write about Jewish artists and writers, teachers and musicians. I love my subjects, every one of them, but I have never written about myself before. This is the first time and my 301st article for the paper.

Three friends from Moscow, three Jewish women from around the world, spent a wonderful week together during their reunion in Vancouver. We are planning to meet again soon. We are not going to wait another 39 years.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected].