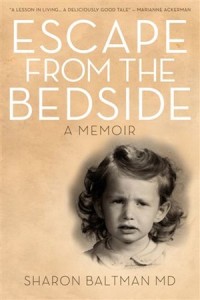

Toronto physician Sharon Baltman treats her patients by listening. Author of the self-published memoir Escape from the Bedside, Baltman, 66, takes readers on the journey of her decision to go to medical school until she ultimately gave up being a general practitioner so she could have more time for her patients.

Currently maintaining a two-day-a-week psychotherapy practice, Baltman, who is divorced with one daughter, said that she escaped “from the ivory tower of the hospital into private psychotherapy practice in order to listen closely to my patients, and hear their stories.”

She said that when she first announced her plans to enter pre-med at University of Toronto, she was told she’d never be a doctor, “because of her long painted fingernails, her big breasts, and the ‘three Ms: marriage, motherhood and medicine.’” She persevered, however, and went into emergency medicine, then family practice.

“I left emergency medicine because I didn’t have enough time for my patients,” she said. “I barely met [them] and rarely saw them a second time.”

She switched to a general practice, she said, “so I would have longer-term connections, but ran out of time trying to deal with both the physical and emotional needs [of the patients].

“In order to hear more about people’s lives, and what made them tick, I finally chose full-time psychotherapy work, so I could have time to listen to their tales in a quiet, un-rushed venue. I chose not to be a psychiatrist, because I did not want to go through another residency.”

While she started with classic Freudian analytic work, she said, she later moved to cognitive behavioral therapy, “to teach patients to deal with the here and now in a concrete way – to reframe their thoughts more positively, and to find the grey zone between the black and white extremes of life.”

It’s only in the last 10 years, Baltman said, that medical schools have trained doctors in narrative medicine, a method whereby physicians do not merely treat medical problems, but take into account the specific psychological and personal history of the patient.

It’s only in the last 10 years, Baltman said, that medical schools have trained doctors in narrative medicine, a method whereby physicians do not merely treat medical problems, but take into account the specific psychological and personal history of the patient.

“It is a way of listening closely to patients’ stories about their illness. Instead of asking, ‘Where is your pain?’ narrative medicine has physicians asking patients to tell them what they need to know about them. By telling us a story, we get a lot more information about [our patients] and their illness.”

For example, she said, if someone comes in complaining of chest pains, “a doctor typically asks where, for how long, and if they’ve had it before. With narrative medicine, the doctor keeps interrogating until they get the whole story. Maybe it’s stress-related, maybe it happens after a certain activity. They try to dig into the story.”

Patient care is much better, said Baltman, if physicians know everything that is going on. “On the [other hand], patients feel heard. An important piece of narrative medicine is that everyone is humanized.”

She said that there are doctors who have been practising narrative medicine for years, “but now it is an important part of medical school curriculum. When students learn about eye disease, they may also read a story about someone losing their vision, so students get an idea of what the patient is going through. They learn about a patient’s experience by reading about them.”

Baltman said that, in retrospect, her career was headed in the direction of her current practice from the beginning. “My career took me here because I wanted to listen. Now, I have the opportunity to talk to my patients.”

– For more national Jewish news, visit cjnews.com.