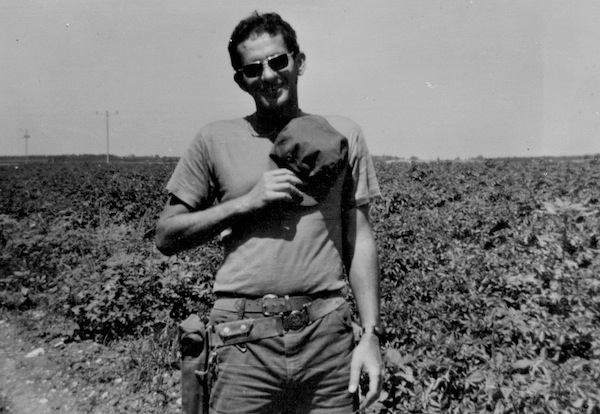

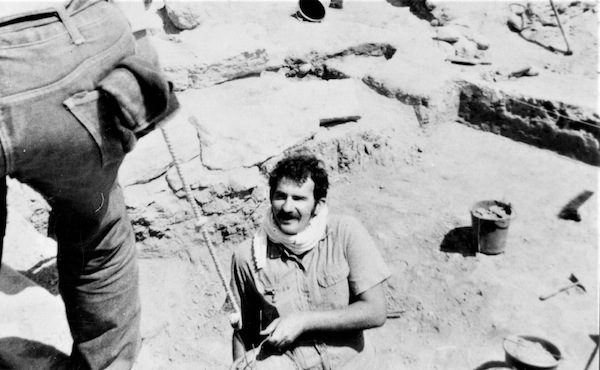

The author took refuge from the perils of the streets by joining a kibbutz as a volunteer. (photo from Victor Neuman)

In this eight-part series, the author recounts his life in Israel around the time of the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The events and people described are real but, for reasons of privacy, the names are fictitious.

Before the War: Part 1

“The bomb shelters can no longer be used as discotheques.”

It was Oct. 6, 1973. Gidon, our kibbutz commander, was announcing that we were under attack and giving us our preparation instructions, including the immediate clearing out of bomb shelters for use in the event of air attack.

Syria had overrun the Golan defences and Egypt was pouring into the Sinai. I was in disbelief over the whole thing. Last year, I was writing my master’s thesis, analyzing Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Now I could be writing something more like Warfare: A Tourist’s Guide. How had my life gone so abruptly from pondering literature to pondering existence?

There’s an expression Israelis use: “I could sell you.” In other words, you are ripe for the plucking and I could easily take advantage.

When I arrived in Israel on my first trip, in 1968, I was totally pluckable. No knowledge of Hebrew. No knowledge of the country. No tour group guide to protect me. All I had was my curiosity about this country that had recently achieved a stunning victory in the Six Day War. I think that event had caught the attention of many like myself, and there was a huge influx of tourists and volunteers to visit this remarkable place.

I was bought and sold in the streets of Tel Aviv. Simply buying a prickly pear fruit was fraught with fraud.

“One-and-a-half lira please,” the street vendor told me. I paid him and started walking away. Then an Israeli stepped up to the stand.

“One-and-a-half lira please.”

This time, the buyer was having none of it. “Yes, one-and-a-half lira, but you’ll take 75 grush.” Leaving no opportunity for a response, he paid what he wanted and took the fruit. I had just paid double for the same thing.

At another time, I tried to be smarter. I needed to change my German marks into Israeli money. I was aware there was a black market for foreign currency and the street usually offered better rates than the bank. It didn’t take long to find a dealer. They can smell a tourist a mile away. One came up to me asking if I had foreign currency to change. I asked him what rate he was offering for German marks. He gave me a number that sounded pretty good and we agreed on a transaction. I handed over the Deutschmarks – he could have bolted but he was an older guy and I figured I could outrun him if I had to.

He took my money and began counting out Israeli currency. I thought there was something odd about the way he wrapped the money around one finger as he flipped the bills and counted them out to me. Later, when he was long gone, I recounted what he gave me and found I was several bills short. He had flipped the bills so that he had ended up counting the same ones twice and giving me less than we had agreed upon. In the end, I was “sold” again and had even less than I would have gotten at the bank.

You never really lose at these things because they always come with lessons. In most cases, you win some and you learn some. The only time you really lose is when misfortune befalls you and you’re sleeping through class.

I took refuge from the perils of the streets by joining a kibbutz near Haifa as a volunteer. Kibbutzim are basically communal societies where all wealth, housing and equipment are owned by the collective. Material perks like TVs or stereos are doled out on a seniority basis. No one – even those running the place – has any real power over others or more wealth than others. The top jobs are considered something to be avoided. You have all the responsibility and headaches of administering the mess without any particular rewards. In my experience, a kibbutznik generally takes the top job when it is their turn in the rotation and they simply can’t get out of it. Socialism in its purest form and no commissar overlords.

Kibbutz life was good. Nobody tried to rob me and, in return for picking grapefruit and oranges, I got accommodation, food, Hebrew lessons and free tours of the countryside. Sometimes, on my days off, I went further afield.

One of those forays was particularly memorable. My girlfriend, Suzanne, was a kibbutz volunteer from Paris and together we decided to attend Independence Day celebrations in Jerusalem. We booked a hotel room in the Arab quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City and thought about our plans for the evening. The debated options were hanging out in the room or going to the cinema to take in a movie that was a modern American take on Romeo and Juliet. Romance won the day and we left for the movie. The movie was mediocre. Things back at the hotel were less so.

When we got back, we were met by police and the hotel manager. The manager apologized for the inconvenience but we were being moved to another room and could we please collect our luggage from the original room. The sight of our old room was amazing. It was all sparkly. The windows were gone and every horizontal surface was covered with dust. Someone had set off a bomb in the alleyway outside our room.

You might think that a bomb blast would send great shards of glass flying across the room. A blast close by doesn’t. Instead, it pulverizes the glass into a fine dust and that’s what is blown across the room. Objectively speaking, the room looked beautiful – like a fantasy bed chamber decorated in fine diamonds. In reality, we were shaken, as we carefully swept the glass from our bags and began hauling them to our new room on the opposite side of the hotel. It was nice. It had windows.

And the movie? We upgraded its rating from mediocre to fantastic.

Suzanne and I had different travel plans and, after Jerusalem, she traveled to be with friends on a kibbutz north of Hadera. I was concerned that I didn’t have enough money to fly home if the need arose. I was also learning very little Hebrew from the kibbutz we had been on and it was getting annoying needing Suzanne to translate for me wherever we went. When we parted, I headed south to find work in Arad, hoping I could make some serious money and learn Hebrew by some kind of immersion method.

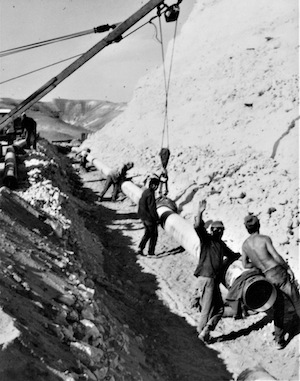

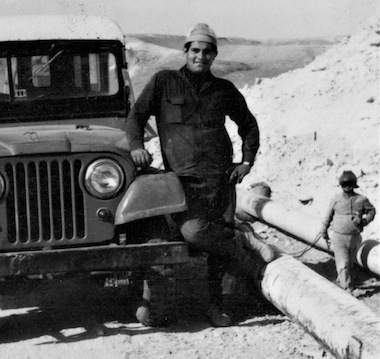

The immersion was profound. I was plunked down in an environment where nobody spoke English. The Arad employment office put me on a crew building a pipeline that would take Dead Sea chemicals to a refinery in Tishlovet. The crew consisted of central European Jews, Israeli Arabs, some local Bedouins and an assortment of thieves, bastards and criminals who were probably one step ahead of an Israeli SWAT team. One of them stole my camera (a beautiful Zeiss Ikon that my father had gifted me) and an assortment of items from all of the crew. We were put up in a motel and, the day the thief quit, he still had the key to the motel room. He made the most of it.

On the job, I was low man in the pecking order. I had to fetch tools when yelled at and woe to me if I didn’t understand what was being asked for. With this bunch, everybody knew only enough English to swear, and little more. I was sworn at in English, Arabic, Romanian, Hungarian, Polish and Hebrew. It was somewhat typical of what I heard in other parts of the country. Israelis have a knack for adopting the choicest insults from all the languages they encounter. Understandable when you come down to it. Spoken Hebrew was basically invented by linguistic scholars around the time the state was created. They had the difficult task of updating ancient Hebrew to cover things like helicopters and toaster ovens. They didn’t spend a lot of time thinking up swear words. Israelis had to improvise and they did a fine job of it.

The upshot was that, in two months on the pipeline, I learned more Hebrew than in a year of kibbutz Hebrew school. I was getting pretty fluent and I had a good ear for the accent. I began to find that, when I spoke, I was often being mistaken for a Sabra. And, as a bonus, I could swear like a sailor.

* * *

Living in Arad, I now had a decent amount of money rolling in from my work. I decided to take an offer from a guy I’ll call Bad Lennie. Bad Lennie was a South African Jew who had immigrated to Israel with his brother, Good Lennie. Good Lennie lived in one part of Arad with his girlfriend; Bad Lennie had his own apartment. When the two of them were in the same room, I noticed Good Lennie seemed somewhat embarrassed around his brother and often cringed when his brother rambled on about his life in South Africa. In time, I found out that he had good reason to be embarrassed.

Bad Lennie was between jobs and needed money, so he offered me a chance to share his flat if I split the rent with him. I couldn’t pass up the chance to leave behind the den of thieves that were my pipeline crew, so I moved in with Bad Lennie.

Bad Lennie had some disturbing fantasies. He had undergone some military training in his home country. He had a lot of stories to tell me about his time in the military. According to him, he was a top-notch officer in command of hundreds of blacks. His favourite story was of the day one of his men questioned his authority in front of the others. Bad Lennie calmly walked up to the offending black soldier and put a bullet in his head. After that he never had trouble with the others. He told me many stories with pretty much the same theme. The den of thieves was starting to look better to me.

Bad Lennie had a revolver. I found out about it one day when he had this huge grin on his face and told me to feel under his arm. I wanted to pass but he grabbed my hand and stuck it in his armpit.

“What do you think? It’s a gun!” What did I really think? He was wearing a holstered gun under a turtleneck sweater! Not a bad James Bond look except that his turtleneck quick draw was going to need some work. I knew he was an idiot but now I was beginning to wonder how dangerous a one.

Bad Lennie pestered me to get him a job on the pipeline so I did. He lasted three days. On the third day, he came up to me and said, “Watch this.” Then he proceeded to go up to our Arab foreman and swear a blue streak at him in English. He turned back to me with that same stupid grin on his face. “It’s OK. The bugger hasn’t a clue what I’m saying.”

I had been on the pipeline long enough to know different. Everybody in this bunch was fluent in Swearese. Bad Lennie was fired. He still seemed confused about why but he was a goner nevertheless. And his problem became my problem. Bad Lennie was getting half the rent money from me but it was not enough and he started borrowing my money. I saw no chance of getting repaid because Bad Lennie now had no job. He spent most of his time hitting on his brother for money and going to the cinema in Beersheva to watch the latest Western. After coughing up a fair amount of cash, I cut him off. Then he offered to sell me some of his coffee table books on Israel. Truth be told, they were beautiful books but I was still living out of a backpack and couldn’t see myself schlepping all that weight.

I said, “No thanks.” He looked pissed but I didn’t care.

One day, I returned from work and walked through the door of our flat. There was Bad Lennie standing kitty-corner across the room with his gun pointed straight at my head. I just froze. I felt a powerful urge to say something but nothing came to mind. Then he pulled the trigger and there was this loud “snap.”

“It’s empty,” and he was grinning again. “I’m just kidding around. I wasn’t really going to shoot you.”

I decided then and there that I had made enough money and my Hebrew would suffice. Bad Lennie’s gun was empty but I was sure he kept bullets somewhere. It was time to get out of Dodge. On the day I decided to leave, I left the job site early and headed for the apartment. I knew Lennie wasn’t around because they were playing a new Western at the cinema. I grabbed all my things and stuffed them in my bag. There was a little room left, so I grabbed Bad Lennie’s books and stuffed them in my bag as well.

Lastly, I wrote him a note: “Hi Lennie, I’m leaving town to go to a kibbutz in the north. Take care and best of luck. P.S. I’ve changed my mind about your books. I’ll buy them after all. Just deduct what they are worth from the money you owe me and we’ll call it even. Cheers.” Then I headed for the nearest road out of Arad and started hitchhiking north. It was a bit nerve-wracking. I wasn’t sure who would show up first – my ride or Bad Lennie. I was in luck. My ride came first and I was on my way to join Suzanne.

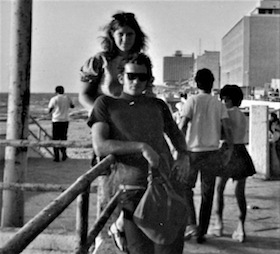

As I mentioned, Suzanne and I had met at our previous kibbutz, near Haifa. She was Jewish and, like me, had come to Israel to check it out and become a volunteer. She was a huge fan of Leonard Cohen and, as a consequence, had a real thing for dark, brooding, handsome Canadians. All I had going for me was the Canadian thing and, happily, she settled for that. For me, the trigger was her incredibly sexy French accent. It was like listening to music.

She also spoke her mind entirely with nothing held back. Tears or laughter came at the drop of a hat and you were never in doubt about what she thought or how she felt. It was a raw honesty of emotion that took some getting used to but, once you did, it was exciting in a scary kind of way. The ride was bumpy but never ever dull. And nothing frustrated her more than people suppressing their feelings. Once, when I was being particularly uncommunicative, she booted me in the rear to try to get me past it. I don’t recall if it worked but, after that, if I felt withdrawn, I made sure I was sitting down.

Suzanne worked in the children’s house and I had a steady job in the banana fields with a guy named Lev as my boss. Banana life was good but there came a time when I worried that I was spinning my wheels. I wasn’t sure I wanted kibbutz life forever and I thought I had the beginning of a career back in Canada. I had a BA in English literature, after all. It had to mean something. I felt I needed to return to Canada and see what I could make of my life there. I was in a dark, who-am-I kind of mood. When I told Suzanne I was going home, she was angry.

“I won’t be the one left behind,” she told me.

Before I knew it, she was on a plane bound for Paris and I was sitting in the middle of a very empty room. Worse than empty. The life had gone out of it. To my surprise, I actually wept. I never realized until then how much I would miss her. Typical of me. Why not save steps? Burn the bloody bridge while you’re still standing on it.

I couldn’t bear that empty room and so, in the time I had left before going home, I joined an archeological dig in the Negev near Beersheva. The work was hot, dirty and finicky. We had to move a lot of dirt to get down to the Iron Age town we were looking for and, at that point, the work had to be much more careful. Every find was scraped, brushed clean, surveyed for location, photographed and, finally, removed to our storage room at the base of the hill.

I was particularly proud of finding an intact Iron Age kiln, circa 700-600 BCE – basically, a three-foot-wide, clay-walled cylinder standing on its end. I carefully brushed and excavated the kiln to its base, always careful to leave the dirt in the centre as support for the walls. After three days of clearing the outside of the kiln and the floor around it, I was told it was time to take it down and go deeper. It had been photographed, measured and catalogued and now it had to be removed. Strangely, my fellow volunteers had all dropped their tools to come and watch me take a pickaxe to the kiln. Not sure what was going on, I swung the pickaxe and buried it in the centre of the kiln. There was a horrible sound of glass breaking.

“Crap!” I thought. “I’ve just destroyed some 2,600-year-old glass artifact that was situated in the middle of my kiln.” Everybody who had gathered round gasped loudly in horror. Feeling disgraced, I dejectedly began pulling out bits of glass. But there was something peculiar. The glass had a colour that was unlike any ancient glass I had ever seen. In fact, it looked a lot like.… “Alright,” I said, “Who buried the frigging beer bottle in my kiln?”

Aside from the pranks, we did a lot of good work and, by the end of the season, I was standing on the streets of ancient Beersheva where Abraham once walked.

When the dig ended for the summer, it was time to go home. My first trip to Israel was over. I returned to Canada in 1970, got an MA in English literature by May 1972 and, damn me, I still didn’t want to teach. I was no further ahead in knowing what I wanted to do. Also, I missed the kibbutz. I decided to go back to Israel later that year. My thinking was that I’d spend some quiet time there deciding about my future. I didn’t realize that I’d have to do my contemplating in the middle of a war.

(Coming up: “When Afula road went quiet”; “Tending the banana fields in war”; “Weapon training begins”; “Near tragedy on guard”; “Fighters return to kibbutz”; “The fire-like impacts of war” and “On return to Canada, life changes”)

Victor Neuman was born in the former Soviet Union, where his family sought refuge after fleeing Poland during the Second World War. The family immigrated to Canada in 1948 and Neuman grew up in the Greater Vancouver area. He attended the University of British Columbia and obtained a BA and MA with majors in English literature and creative writing. Between 1968 and 1974, he made two trips to Israel, one of which landed him on a kibbutz at the time of the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Upon his return to Canada, he studied survey technology at BCIT and went on to a career of designing highways for the Province of British Columbia. When he retired, he reconnected with his roots in creative writing and began writing scripts for Vancouver Jewish Folk Choir concerts and articles for the Jewish Independent. Neuman and his wife, Tammy, live in southeast Vancouver and enjoy the company of friends, their extensive extended family and their four sons.