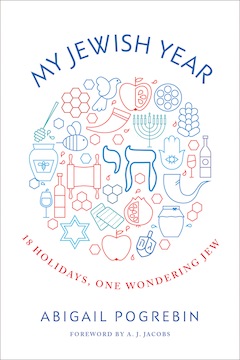

Abigail Pogrebin, author of My Jewish Year: 18 Holidays, One Wondering Jew. (photo from Abigail Pogrebin)

A few years ago, author Abigail Pogrebin spent an immersive year studying the Jewish calendar and attempting to observe it. She chronicled her experience in a column in the Forward and, subsequently, in the book My Jewish Year: 18 Holidays, One Wondering Jew (Fig Tree Books, 2017). On Nov. 19, she was in Winnipeg for the city’s Tarbut Festival.

“I did not approach this as a gimmick,” she told the Independent. “It was really a sincere stab at an understanding I never had, which is the origins for all of these chaggim [holidays] … and also, not just the origins, but the underpinnings, because these are obviously … human-created milestones that have endured for thousands of years. I wanted to understand both how and why they were conceived – what they’re supposed to mean for us today, not just to our ancestors. I definitely had a hunch that, for something to have endured for as long as it has, it has to resonate wherever you are in your life – at least for a large swath of people who live by this calendar.”

Pogrebin recognizes that there is a segment of the population that adheres to it simply because they inherited it, without questioning. Yet, for many people, Jewish observance, particularly of holidays, is a deliberate choice.

Pogrebin grew up in New York City. Her mother, writer and activist Letty Cottin Pogrebin, was instrumental in promoting women’s rights in the 1970s, and her writing includes analyses of what it means to be Jewish and female.

“I was not someone who celebrated nothing before this,” said Abigail Pogrebin. “I had sort of the five or six tent poles of Jewish holidays in my life…. I grew up with Shabbat…. It wasn’t enforced, but it was observed when we were together as a family. I went to synagogue on the High Holidays. We had always lit the menorah for eight nights, and I went to two seders back-to-back. Then, also, the feminine seder, which was a tradition that was started in mid-1970s by a group of women, including my mother.

“So, those were the basics that I’d grown up with. But, obviously, I was missing the majority of the signposts of the Jewish year. It bothered me that I didn’t know [them]. I also wanted to experience them in a way that might lead me to more meaning in my life.”

As examples of what she learned on her journey, Pogrebin said she had never understood before that the process of atonement and introspection needs to start far in advance of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

As examples of what she learned on her journey, Pogrebin said she had never understood before that the process of atonement and introspection needs to start far in advance of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

“During the month of Elul, we’re supposed to do what is called, in Hebrew, cheshbon hanefesh (accounting of the soul). And, when I asked various rabbis how I might go about that, because there’s not a clear blueprint for observance, quite a few suggested taking the middot (characteristics) and breaking them down, exploring one a day. So, I chose to do that for 40 days leading up to Yom Kippur.

“I did this with a friend, a study partner, essentially. So, my friend, Catherine, and I took these 40 middot that a rabbi had posted online. One day, you’d do anger, another you’d do courage, another envy, another humility.”

As the women went through the days, they aimed to look at themselves as deeply and honestly as they were able and to write their reflections on each characteristic at the end of each day.

“By the time I got to synagogue on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, I felt like I was in a very different zone for reflection,” said Pogrebin. “On Yom Kippur, I went to a mikvah [ritual bath] for the first time, and that was extremely meaningful.”

Pogrebin spent Sukkot in Los Angeles, interviewing four rabbis in two days, with each one discussing a different aspect of Sukkot that she never had understood before.

“One emphasized the fragility, the impermanence of our structure, and our shelters in our lives,” she explained. “How resonant that is today, with natural disasters and poverty, and all kinds of things that should shake our foundations, both literally and metaphorically.

“Another talked about the fertility, the imagery that is in Sukkot – the shaking of the lulav and etrog, which was much racier than I ever understood. Another talked about agriculture, and the land and connecting – reconnecting with the earth in ways we don’t do in other times of the year.

“Another rabbi talked about wandering, the importance of being lost and being comfortable with being lost; embracing the idea of the most important lessons and reckonings when we don’t know where we are going.”

Pogrebin also mentioned Yom Hashoah, which commemorates victims of the Holocaust. According to her, not many people know when it takes place. “I think it’s just not in the fabric of how many of us were raised, but it seems to me to be a crucial holiday, even though it could never be adequate to mark such a vast and devastating history and persecution,” she said.

“I went to B’nai Jeshurun, which is a Conservative synagogue on the Upper West Side that, in partnership with the JCC in Manhattan, does something called the naming of the names, where they have this book from Yad Vashem … devastating lists of families who perished. Starting at 10 p.m. and going all night into the next day, people tak[e] turns reading those names,” said Pogrebin.

About how the yearlong experience has changed her and her family, Pogrebin said, “In a way, it’s changed completely and, in a way, it hasn’t changed radically. I’d say it’s changed completely in the sense that I don’t look at time, relationships, obligations, the same way anymore. I think, if the holidays do anything, they are constantly reminding us to ask ourselves who we are in the world and whether we are doing what we could be doing to alleviate someone else’s suffering or pain.”

Pogrebin is always looking for ways to bring the lessons of her journey into her day-to-day life, to make them come alive in a way they didn’t for her when she was a child.

About the book, she said, “If one wants to understand the arc of the year, you will. It’s not that there are not people who might disagree with this or that, but it was researched and tested with people who live this and teach this at a very high level. So, it’s not just Abby saying it to be true. It’s me putting on my journalist hat and making sure when I explain something that it’s definitely rooted in scholarship. I hope … it’s an enjoyable and entertaining book.

“The people who read it are coming along with me and my experience with the holiday for the first time. They are also getting, I think, a fairly thorough template of what a Jewish year involves and demands. I think that, whether you’re Jewish or an interfaith family that wants to explain or introduce … some of these holidays in your own home and you’ve never done them before, it’s absolutely a door into learning how.

“There is something magical,” she said, “about not just living by someone else’s clock, but by an ancient roadmap…. I think there’s something very powerful about embracing … whether it’s Judaism or any religion, what it imposes on you, in terms of [laying out] what you should be thinking about besides your own needs and wishes – to me, that’s an important takeaway that I think other people should explore.”

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.