Gilad Seliktar, left, and Rolf Kamp in Amsterdam. They are drawing the last hiding place of Nico and Rolf Kamp in Achterveld, which was liberated in April 1945 by Canadian troops. (photo from UVic)

A University of Victoria professor is orchestrating an international project that links Holocaust survivors with professional illustrators to create a series of graphic novels, thereby bringing the stories of the Shoah to new generations.

Charlotte Schallié, a Holocaust historian and the current chair of UVic’s department of Germanic and Slavic studies, is leading the initiative, which connects four survivors living in the Netherlands, Israel and Canada with accomplished graphic novelists from three continents.

The project, called Narrative Art and Visual Storytelling in Holocaust and Human Rights Education, is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Its aim is to teach about racism, antisemitism, human rights and social justice while shedding more light on one of the darkest times in human history.

UVic is partnering with several organizations in the project, including the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg, the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam and the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre.

Many historians of the genre have argued that the rise of graphic novels as a serious medium of expression is largely due to the commercial success of Art Spiegelman’s Maus in 1986. Maus, the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize, depicts recollections of Spiegelman’s father, a Shoah survivor, with Jews portrayed as mice, Germans as cats and Poles as pigs.

Schallié told the Independent that the idea for the project came from observing the interest her 13-year-old son has in graphic novels and the appeal Maus has had among her students, who have continually selected it as one of the most poignant and memorable materials in her classes.

“Though a graphic novel, Maus could hardly be accused of treating the events of the Holocaust frivolously,” she said from her office on the campus of the University of Victoria.

As most survivors are now octogenarians and nonagenarians, the passage of time creates an ever more compelling need to tell their stories as soon as possible.

“Given the advanced age of survivors, the project takes on an immediate urgency,” said Schallié. “And what makes their participation especially meaningful is that each of them continues to be a social justice activist well into their 80s and 90s. They are role models for the integration of learning about the Shoah and broader questions of human rights protection.”

The visual nature of a graphic novel allows it to bring in elements or depict scenes that are not possible with an exclusively written work, according to Schallié. A person may describe an event in writing but leave out aspects of a scene that might add more to the sense of what it was like to be there at the time.

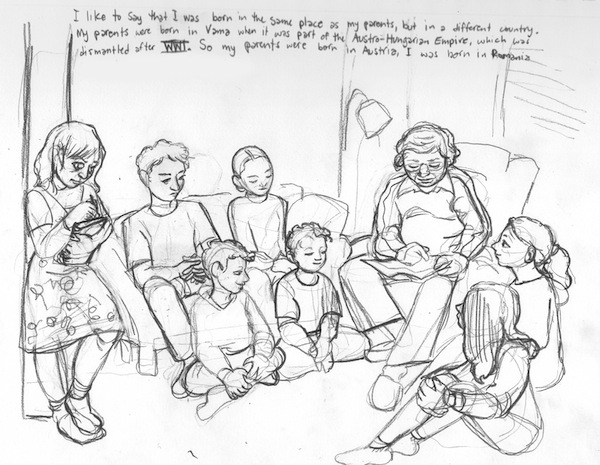

One of the survivors participating in the project, David Schaffer, 89, lives in Vancouver. He is paired with American-Israeli comic artist Miriam Libicki, who is also based in the city. The two met in person in early January so that Libicki could learn the story of how he survived the Holocaust as a child in Romania.

In 1941, Schaffer was forcibly sent with his family to Transnistria, on the border of present-day Moldova and Ukraine, by cattle car. There, they suffered starvation and were subjected to intolerable and inhumane living conditions.

“The most important thing is to share the story with the general population so they realize what happened and to avoid it happening again. It’s very simple. History has a habit of repeating itself,” said Schaffer.

Libicki, who was the Vancouver Public Library’s Writer in Residence in 2017, is the creator of jobnik!, a series of graphic comics about a summer she spent in the Israeli military. An Emily Carr University of Art + Design graduate, she also published a collection of essays on what is means to be Jewish, Toward a Hot Jew. (See jewishindependent.ca/drawing-on-identity-judaism.)

“The more stories, the better. The wiser we can be as people, the more informed we can be as citizens and the more empathy we can have for each other,” Libicki said. “Graphic novels are not just a document in the archives; they’re something people will be drawn to reading.”

The other illustrators are Barbara Yelin, a graphic artist living in Germany, and Gilad Seliktar, who is based in Israel. Yelin is the recipient of a number of prizes for her work, including the Max & Moritz Prize for best German-language comic artist in 2016. Seliktar has illustrated dozens of books – from publications for children to adult graphic novels – and his drawings frequently appear in leading Israeli newspapers and magazines.

Brothers Nico and Rolf Kamp in Amsterdam and Emmie Arbel in Kiryat Tiv’on, Israel, are the other three survivors who are providing their accounts of the Holocaust.

The books will be available digitally in 2022. A hard copy version of each book is planned, as well. When finished, the graphic novels will be accompanied by teachers guides and instructional material designed for schools in Canada, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States.

UVic hopes to match a larger number of survivors with professional illustrators in the future. To learn more, contact Schallié at schallie@uvic.ca. You can also visit the project’s website at holocaustgraphicnovels.org.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.