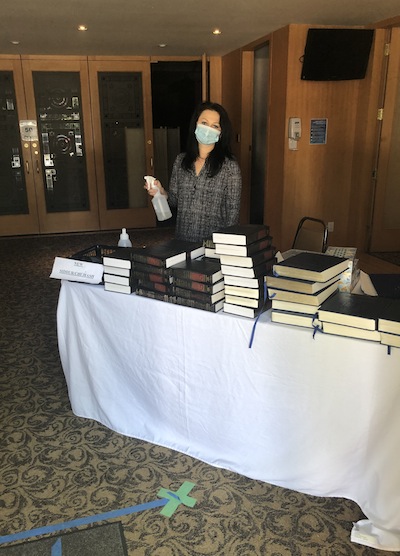

Services in the Schara Tzedeck auditorium, with social-distancing measures in place. (photo by Camille Wener)

In early March, Canadians were just beginning to take COVID-19 seriously. Then, in what seemed like an instant, the province shut down all places where people gather. Religious organizations were forced to close their doors – in some cases for the first time in more than a century – and rethink everything about how they engage with their congregants.

In a survey of rabbis and synagogue leaders across British Columbia after a summer of COVID, what emerges is not so much a story of hardship and difficulty but of resilience, creativity and a paring away of the superfluous to rediscover the most elemental things that we seek from spirituality and community.

The loss of life, the horrible illness and difficult recovery have directly affected thousands of British Columbia families, but we have fared better than many other jurisdictions. Even those not directly affected by the virus itself have had heartbreaking occasions, such as losing loved ones to other causes without family beside them, funerals and shivahs conducted online and, of course, the various burdens and isolation experienced by older people, those who live alone or others who are especially vulnerable.

As we approach High Holidays that are assured to be unlike any we have experienced before, there is an air of anxiety, but more evident is a flexibility and commitment to make the holidays as meaningful as possible. Although close coordination has taken place through RAV, the Rabbinical Association of Vancouver, every congregation is finding its own way and the holidays in most cases will occur along a spectrum of hybrid in-person and online services, most with multiple smaller, shorter programs. Services that routinely occur outdoors, such as Tashlich, will be joined in some cases with shofar-blowing and other services held out of doors. Despite all, reaction among rabbis is that community engagement and flexibility have made these months far better than could have been predicted in March.

“From day one, our motto was, we are not ramping down, we are ramping up,” said Rabbi Jonathan Infeld. His Conservative shul, Beth Israel, had not previously done programs or services online but, within 24 hours of the shutdown, all activities had moved online.

Zoom, an online meeting platform that almost no one had heard of before the pandemic, has proved a lifeline for individuals and communities, including almost all synagogues in the province. The platform’s interactivity allows individuals to participate in services, make virtual aliyot, engage in back-and-forth with teachers and guest speakers, and participate from home in numbers that rabbis say are routinely higher than in-person programs in “normal” times. “The social community of the synagogue’s remained intact,” said Infeld.

Most of Beth Israel’s congregants will experience the High Holidays from home, online. “It’s only the people who are leading the services and/or their families who will be in the building,” he said.

Provincial regulations permit a maximum of 50 people in any gathering, with social distancing enforced. For synagogues, that number varies based on the size of a sanctuary and the reality is that, to ensure two-metre separation, smaller synagogues will be able to accommodate far fewer than 50.

For the Orthodox Congregation Schara Tzedeck, however, online Shabbat and holiday services are not an option.

“We’ve had to think very creatively,” said Camille Wenner, executive director of the synagogue. “This was the first time in 110 years that our doors closed for davening,” she said.

People who had made minyan every week of their life suddenly couldn’t.

“That was really difficult,” said Wenner. “That’s why it was so important for us to mobilize a chesed committee to connect with everyone and make sure that everyone was OK. That’s how the idea of Shabbat in a Box developed and the idea of feeding people and making them feel that that ritual of Shabbat is still very much alive, you don’t have to be here to do it, we can still do it together.” That concept will be extended to Rosh Hashanah in a Box, which will go to more than 300 households.

Schara Tzedeck was the first Orthodox synagogue in Canada to reopen to limited in-person services, on June 1. “It was nerve-racking,” Wenner admitted. The usual single Shabbat service has been increased to two. Hand sanitizers and masks are required. Those who do not bring their own siddur are handed a newly cleaned one. Additional custodial staff are on hand to wipe down the entire sanctuary between services. An online registration program allows congregants to see how many of the 50 seats remain available.

For the holidays, services will be expanded to meet demand, she said. Rabbis and cantors who work in day schools and elsewhere in the community have volunteered to lead smaller services, which will occur in various places throughout the building and may even take place under a tent in the parking lot, if need be.

“The services will be condensed to about two hours instead of the regular five,” she said. “Right now, we’re looking at six or seven services back to back starting at 6:30 in the morning.”

The Peretz Centre for Secular Jewish Culture normally doesn’t run programming through the summer. But, this year, the Sholem Aleichem Speakers Series has continued every Friday on Zoom and Exploring Jewish Writers, on Saturday mornings, also has continued through the summer, said Donna Becker, the centre’s executive director. “Both of them are better attended on Zoom than they were in person,” she said.

Peretz Centre holiday services will feature Stephen Aberle singing Kol Nidre, but the usual musical program, which sees the Vancouver Jewish Folk Choir interspersed with the audience, is obviously out of the question.

This year’s High Holidays will be the first since the inception of the progressive congregation Ahavat Olam in 2004 that will not be held at the Peretz Centre. Said board member Alan Bayless: “We would prefer not to use computers for Shabbat or High Holiday services, but we believe that virtual services are necessary for our community this year given the danger of the coronavirus.”

Rabbi Yitzchak Wineberg of Chabad Lubavitch BC, said the 10 Chabad centres in the province are all adopting protocols appropriate for their congregants’ needs. He worries that, with daily infection reports often heading in the wrong direction, the province may re-impose stricter regulations by the time the holidays roll around. Either way, he suspects many or most people will be marking the holidays at home. “It’s the reality,” he said. “It’s a question of what works and what is acceptable and what isn’t.”

On the positive side, online learning has skyrocketed.

“The amount of study that’s going on by Zoom is absolutely unprecedented,” Wineberg said. “That’s the silver lining. I have a feeling that it will continue once this pandemic is over, God willing as soon as possible, I think people are going to continue learning that way. You have the convenience of sitting in your home and participating almost as if you are there – that’s the new reality.”

The Reform synagogue Temple Sholom had a running leap at livestreaming services, so some of the infrastructure was well in place before the pandemic. The difference now is the effort they are going to not just to allow people at home to observe, but to participate in the services. Classes, webinars and other programs have been expanded online. The Men’s Club and the Sisterhood have moved their programs onto Zoom. The accessibility means Temple Sholom programs are reaching new audiences, often far outside Vancouver.

The summer weather has allowed the synagogue to hold some events in parks and in the courtyard behind the shul. Still, Rabbi Carey Brown has no illusions that these High Holidays will be like any other. For one thing, only clergy will be in the sanctuary.

“It will be really different,” said Brown, who is the synagogue’s associate rabbi. “We are working really hard to put together High Holiday services and experiences that will help people feel the sense of the season, both the newness of the new year and the reflectiveness of the season.”

The Okanagan Jewish Community, which does not have a permanent rabbi, has depended on volunteers to deliver programs and services. The Kelowna-area centre has seen significant growth, and is running an 11-person conversion class and various adult education programs on Zoom. As great as all that is, Steven Finkelman, the centre’s president, thinks this might be a tough year financially for the group, a concern expressed by several interviewees. Revenue generated at the High Holidays and through in-person galas or other fundraising events in normal years is likely to suffer this year.

While online programming has proven hugely popular, there can be no denying that this experience has resulted in some missed opportunities. Rabbi Philip Gibbs of West Vancouver’s Conservative shul Har-El, has pangs of regret when he thinks back to the grand plans the synagogue had in January for a year of innovation and new initiatives.

“I was very excited about both the scale and the types and the variety of programming – more cooking events or culturally focused programs that really were going to give our community the chance to gather and engage in a really fun, exciting and meaningful way,” he said. “Unfortunately, we’ve lost that opportunity.”

The challenges and opportunities of the High Holidays will be met with one or more services on different days, he said. While he and his congregation are making the best of the situation, Gibbs laments the loss of in-person collective connection.

Similarly, Rabbi Hannah Dresner of Or Shalom, which is affiliated with the Jewish Renewal movement, grieves the loss of some in-person connections. However, she feels that Zoom can provide an intimacy that a large group gathering might not. As well, not only are out-of-towners joining Or Shalom’s offerings, but the rabbi and others are surfing programs throughout the Jewish world and beyond.

“I just think it’s a time when the world is our oyster,” said Dresner. “Spiritually you can look for whatever kinds of workshops you want, so people are experimenting a lot more.”

Or Shalom will hold successive Tashlich services at False Creek, each accommodating congregants in limited numbers. For the well-being of ducks and other birds, Or Shalom members drop leaves rather than bread in the water.

“I love the creative challenge, but I can’t say it doesn’t keep me up at night,” Dresner said, laughing. “I hear a lot of rabbis say, I didn’t sign up for this. There’s nothing that we’re doing that I signed up for.”

This extraordinary time has forced and invited rabbis and others to reconsider everything. The changes have made her reflect on “what’s at the heart of the service, what do we really need, what’s extraneous, what makes it tedious? Because it cannot be tedious. It’s got to be tight, shorter and beautiful.”

Rabbi Levi Varnai of the Bayit in Richmond concurs that the crisis forced a reckoning. “If a synagogue is not doing services – and we don’t do services online – what do we do? It got us thinking to the real core of what a synagogue is really supposed to be about,” he said.

As an Orthodox shul, the Bayit cannot stream services on Shabbat or the holidays, but they have expanded classes throughout the week and held socially distanced events at Garry Point Park. Pre-Shabbat events help people prepare for the Sabbath and regular phone calls and visits by the rabbi and volunteers to speak with people from a distance and drop off packages keep a sense of community alive.

Now that limited in-person gatherings are permitted, the shul’s size permits 25 congregants. But even that is not quite as it was. “It’s coming in, praying and going, which is great because it’s more than we had before that,” he said, but there’s no food and no kibbitzing.

The holidays will see multiple services and people can arrange to be there specifically for Yizkor but perhaps not come for the entire day.

The chaos of shifting suddenly from the way things have always been done has not left Varnai a lot of time to reflect. But, when pressed, he acknowledged how surreal it is.

“It’s a huge change to the regular Jewish life that I’m accustomed to since I was a young boy, since my bar mitzvah, praying three times a day with a quorum of others,” he said. It’s a stunning transformation, but entirely within Jewish tradition. “We always put safety and well-being and health first.”

He puts the whole thing in perspective. “Our people came out of the centuries and had to go through a lot worse,” he said. “Not going to synagogue is not fun but, thank God, other generations were challenged with much greater hardships and we’re relatively blessed.”

Beth Hamidrash, the only Sephardi synagogue in Canada west of Toronto, counts among its congregants Dr. Jocelyn Srigley, a microbiologist who is a director with the infection prevention and control branch of the Provincial Health Services Authority. Rabbi Shlomo Gabay and shul president Eyal Daniel credit Srigley with helping guide them through this difficult time and say it was on her advice that their synagogue was the first in the city to close.

Despite the challenges, however, engagement is better than ever, said the rabbi. Daniel added that synagogue membership has actually jumped 20% since the pandemic began, something he credits to an increased desire for meaning, and also a direct outreach he began when he became president in June to encourage occasional attendees to commit to membership.

The strange situation has also helped strengthen relations between Beth Hamidrash and the two Sephardi congregations in Seattle. They virtually co-hosted an Israeli historian speaking on Medieval Spain, for example.

Probably no rabbi has had an experience quite like Rabbi Susan Tendler. The new spiritual leader at Richmond’s Conservative shul Beth Tikvah arrived in the midst of the lockdown with her family from her previous posting in Chattanooga, Tenn. The family then had to quarantine for 14 days, with community members dropping off prepared meals and greeting the family from a distance. Despite that unusual arrival, or perhaps because of it, she has reflected on big things.

“While I would never wish the pandemic on this world or on any person, really, this is an opportunity for renewal,” she said. “We do all have to reconsider what we’re doing and what our goals are and find new paths for reaching them.”

While hoping that services might return to normal in the not-too-distant future, she acknowledged that the very term sanctuary implies that every congregant must feel secure. “At a minimum,” she said, “it has to feel safe.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been amended to reflect that Or Shalom is affiliated with the Jewish Renewal movement, not the Reconstructionist movement, as stated in the original online and print versions.