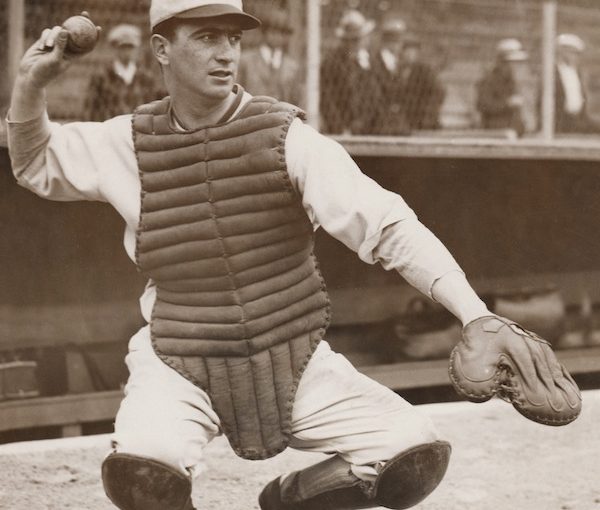

Moe Berg as a catcher during his time in Major League Baseball. (photo from Irwin Berg)

Near the end of John Ford’s essential 1962 western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a newspaper editor coins the credo, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

The fact, as we all know, is that Americans are all-star myth-makers and myth-lovers. Many American Jewish boys caught the bug via the improbable immigrant saga of Moe Berg, a paradoxically brilliant professional athlete who led a secret second life as a spy for the U.S. government. How much of Berg’s story is true, though, and how much was legend passed among kvelling kids in the schoolyard?

Aviva Kempner, who hit a home run with her 1998 documentary about another Jewish ballplayer, The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg, was the obvious, natural and best-equipped filmmaker to take on the mid-20th-century mysteries at the heart of Berg’s minor celebrity.

The Spy Behind Home Plate, which screens at the Vancouver Jewish Film Festival March 8 at the Rothstein Theatre, is a testament to Kempner’s determination and persistence. Chock full of dozens of contemporary and archival interviews, and packed with rare photos and even rarer film footage, The Spy Behind Home Plate is a definitive record of Berg’s achievements.

Although it’s an effective way to impart information, the dogged, dog-eared marriage of talking heads, vintage visuals and period music can’t fully evoke the shadowy stealth and deadly risks of Berg’s wartime activities. Hamstrung by her budget, Kempner wasn’t able to stage reenactments or employ other strategies to illustrate the unfilmed and unrecorded liaisons and conversations that Berg had in Europe in 1944 and 1945. The Spy Behind Home Plate, therefore, is like the steady everyday player who notches the occasional three-hit game but never achieves the transcendent grace and power of a superstar.

Morris (Moe) Berg, international man of mystery, was born in New York in 1902. His father had fled a Ukrainian shtetl for the Lower East Side, where he started a laundry before buying a drugstore in Newark.

The family moved to New Jersey when Moe was a boy, and he grew into an excellent student and a terrific baseball player. After a year at New York University, he transferred to Princeton, where he was a star shortstop (back when the Ivy League was the top, if not the only, sports conference) and graduated Phi Beta Kappa.

While his older brother Sam fulfilled Dad’s wishes and went to medical school, Moe signed a contract to play pro ball. He acceded to his father’s demands up to a point by attending Columbia Law School in the off-seasons, earning his degree and passing the New York bar in 1929.

It was a false bargain: Moe despised the idea of being a lawyer, while Bernard Berg never accepted a baseball career as a legitimate pursuit. In fact, the old man refused to go to the park and see his son play.

From an athletics standpoint, his dad wasn’t missing much. A knee injury early in Moe’s career, compounded by primitive diagnosis and treatment, severely slowed him. Over 15 years as a backup catcher, Berg notched exactly 441 hits in 663 games.

What set Moe apart was his charm, charisma and erudition. He studied Sanskrit at the Sorbonne one off-season, and read multiple newspapers every day. When he went to Japan on a barnstorming tour with Babe Ruth and other Major League stars, he learned Japanese.

Berg carried a camera everywhere on that trip, and made a point of checking out the roof of a tall Tokyo hotel in order to shoot a 360-degree panorama of the city. It’s not altogether clear if he was already working officially (albeit surreptitiously) for the U.S. government, but his film was of significant help when the United States went to war with Japan after Pearl Harbor.

In fact, in early 1942, Berg recorded a radio segment in Japanese that was broadcast in Japan and drew on the goodwill he’d accumulated over two prewar visits.

Berg had been sent on research missions to South America, but that was too far from the real action. It appears he found a home in 1943 in the newly created Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the intelligence branch that evolved into the Central Intelligence Agency after the war.

His primary and crucial assignment was to ascertain how close the Germans were to having a nuclear weapon, and to sway Italian scientists from the Axis to the Allies. To successfully carry off his cover story, Berg was briefed on the science and strategy of the Manhattan Project.

One biographer recounts, “The OSS had given the Manhattan Project its own spy, in effect, its own field agent to pursue questions of interest wherever he could in Europe. And that was Moe Berg.”

Kempner accords a great deal of screen time to this episode in Berg’s clandestine career as a professional spook. It’s a great story, in which the solidly built former catcher is assigned to attend a conference in Switzerland and determine – from the keynote speech by a visiting German scientist, Werner Heisenberg – if the Nazis are within reach of perfecting the bomb.

Berg carries a pistol to the symposium, with orders to use it on Heisenberg if he deems it necessary. It would be churlish of me to recount the outcome of Berg’s suicide mission except to say that the catcher-turned-spy who spoke seven languages lived unhappily ever after the war.

Kempner leaves us wanting to know more about Berg’s later years. By the weirdest of coincidences, Sam Berg headed a group of doctors sent to Nagasaki to study the effects of radiation poisoning. Incredibly, Moe and Sam never knew about each other’s exploits. This lone fact reveals that there’s still more to know about Moe Berg’s story.

The Vancouver Jewish Film Festival runs until March 8. For tickets and the movie schedule, visit vjff.org.

Michael Fox is a writer and film critic living in San Francisco.