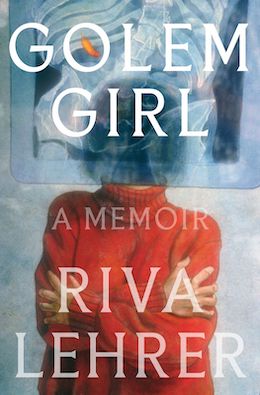

Riva Lehrer, author of Golem Girl, recently spoke on the topic Art Celebrating JDAIM (Jewish Disability Awareness, Acceptance and Inclusion Month). (photo from JBF)

Artist, writer and curator Riva Lehrer spoke at this month’s Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival on the topic Art Celebrating JDAIM (Jewish Disability Awareness, Acceptance and Inclusion Month). Lehrer’s work focuses on issues of “physical identity and the socially challenged body.”

In the Feb. 7 Zoom talk from her home in Chicago, Lehrer discussed her 2020 illustrated memoir, Golem Girl,and her life as an artist born with disabilities into a world determined to “fix” her. Later in life, she found freedom through the flourishing disability arts movement.

Lehrer was born in 1958 with spina bifida. Throughout her early years, the message she received from those around her was that she was broken and would never have a job, a romantic relationship, or an independent life.

The memoir is comprised of two parts. The first deals with growing up in a time when people with disabilities were supposed to be hidden away from the rest of the world. The second looks at reaching adulthood after being raised to think that she was a mistake.

“I grew up thinking I was always wrong and always needed to be fixed, not just from medical professionals, but from everyone in society, who treated me like something to stare at or feel pity for. A lot of the book is taking that apart and addressing why people are stigmatized,” she said.

During Lehrer’s youth in Cincinnati, most children with a condition like hers were institutionalized. There was not a lot of modeling as to how to parent a child with disabilities. Lehrer, however, does credit her mother, who had worked as a medical researcher, for being much less fearful of the situation than an average parent might have been and for refusing the inclination to have her institutionalized.

Lehrer attended a school for children with impairments. “When you are surrounded with others like you, you are just a kid. You stop thinking you are different,” she recalled. The downside, however, was that kids at the time were not encouraged to imagine what they could be as far as a career, and high schools and colleges were not obligated to admit people with disabilities.

“The force of the message that I was a mistake was pretty powerful. By the time I was 12, I knew I was going to live in a body like this forever,” she said.

A resulting feeling of self-loathing persisted until her mid-30s, when novelist and disability rights activist Susan Nussbaum invited her to meet with a group of artists in Cincinnati. Lehrer reluctantly agreed to go and found it a life-changing experience.

“The sight of a lot of disabled people who were not hiding, and who were also funny and bright, gave me a way to understand my life and not just endure it,” she said.

The group showed Lehrer that disability is an opportunity for creativity and resistance. Finding inspiration and empowerment from people in the group, Lehrer asked them if she could paint their portraits. Even though she worked in portraiture, she “was very aware that she never saw images of people with disabilities ever, in museums or classes, only in telethons. It was never anything good.”

Nowadays, she said, her main interest is how people deal with and survive stigmatization. These are at the forefront of the 65 images contained in her book. Among the works she shared at the talk were a charcoal portrait of Nomy Lamm, an amputee musician, political activist and director of Sins Invalid in the Bay Area; a charcoal image of Mat Fraser, a British actor, writer and performance artist who was a regular cast member in American Horror Story: Freak Show television series; and a painting of Liz Carr, a British comedian, broadcaster and international disability rights activist.

Nowadays, she said, her main interest is how people deal with and survive stigmatization. These are at the forefront of the 65 images contained in her book. Among the works she shared at the talk were a charcoal portrait of Nomy Lamm, an amputee musician, political activist and director of Sins Invalid in the Bay Area; a charcoal image of Mat Fraser, a British actor, writer and performance artist who was a regular cast member in American Horror Story: Freak Show television series; and a painting of Liz Carr, a British comedian, broadcaster and international disability rights activist.

“There is such a story behind each of these people,” Lehrer reflected.

As for the title, Golem Girl, Lehrer revealed a lifelong fascination with monsters. “One of the things monsters do is that they break boundaries,” she said. “Dead and moving, animal, person, person and machine, there is always something that violates a boundary. I was thinking how much this is like disability, that people don’t understand the disabled body. They think it is not human in some way. It is treated like it is alien.”

Lehrer is a faculty member of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and an instructor in medical humanities at Northwestern University.

The discussion was moderated by book festival director Dana Camil Hewitt.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.