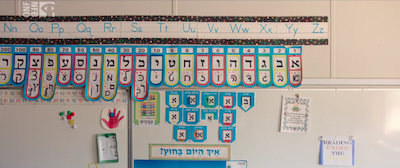

Stills from the NFB’s Highway to Heaven: A Mosaic in One Mile. Richmond Jewish Day School is one of the institutions featured in the short film, which screens at this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival.

The National Film Board short Highway to Heaven: A Mosaic in One Mile, written and directed by Sandra Ignagni, is visually striking. For the most part, it lets the images do the talking, communicating more about cultural diversity than words could.

Part of this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival, Highway to Heaven introduces viewers to the multiple faith groups and institutions along a mile-long section of No. 5 Road in Richmond, which includes Richmond Jewish Day School. In the 17-minute documentary, this strip of road – which has been called “Highway to Heaven” – appears both full of colour and action, as well as remote and removed, not just geographically but with chain link fencing and other security measures.

“We share a world grappling with ethnic and racial tensions, religious xenophobia and violence,” writes Ignagni in her director’s notes. “Such realities are not limited to the world’s conflict zones – they are a part of everyday life, even in the most advanced democracies such as Canada. It was in this context that I was drawn to the peculiar landscape of No. 5 Road … where multiple cultural and religious groups share a short stretch of suburban road. I was curious about how groups pitted against each other in so many corners of the world appeared to be living relatively peacefully with one another, and in very close proximity, in an ordinary Canadian suburb.”

In showing the beauty of the area – both in landscape and in cultural acceptance – Ignagni also captures some of the tensions that exist. The camera jumps from a lush orchard to a mansion mid-construction to a for-sale sign in front of what seems to be part of a forest. In one scene, which looks like it was filmed at RJDS, police in full gear – bulletproof vest and holstered weapons – address RJDS and Az-Zahraa Islamic Academy students, introducing themselves so that the kids should feel comfortable going to the police if they have a problem. The police then referee the kids in a game of ball hockey – boys against the boys, girls against the girls – throwing in questions about boundaries and other issues for the kids to consider.

In showing the beauty of the area – both in landscape and in cultural acceptance – Ignagni also captures some of the tensions that exist. The camera jumps from a lush orchard to a mansion mid-construction to a for-sale sign in front of what seems to be part of a forest. In one scene, which looks like it was filmed at RJDS, police in full gear – bulletproof vest and holstered weapons – address RJDS and Az-Zahraa Islamic Academy students, introducing themselves so that the kids should feel comfortable going to the police if they have a problem. The police then referee the kids in a game of ball hockey – boys against the boys, girls against the girls – throwing in questions about boundaries and other issues for the kids to consider.

Referring to the police presence on the road, Ignagni writes that it could “be variously interpreted as bridge-building, protection or surveillance. I learned that, for more than one decade, the Richmond Jewish Day School did not have an exterior sign for fear of antisemitic attacks against its schoolchildren. And, in recent years, the secular residential community that surrounds No. 5 Road launched a major campaign opposing the proposed expansion of a Pure Land Buddhist temple, using the pejorative moniker ‘Buddha Disneyland’ to describe the proposed building in local media and public debates. The mere fact that zoning by-laws have ordered these communities – the majority of which play a critical role in new immigrant and refugee resettlement – to the fringe of suburban land is also ripe for reflection.”

The minimal use of narration or interviews in the film was a deliberate choice. To do otherwise, Ignagni notes, “would be an exercise in public relations, reducing complex issues to soundbites and polemics. Instead, I wanted to make a film that would at once capture the remarkable – because it is truly remarkable – diversity on No. 5 Road, as it actually exists, while gesturing to some of the unresolved issues that underlie Canadian multiculturalism. The film is, therefore, constructed as a ‘mosaic’ – defined by writer and activist Terry Williams as ‘a conversation between what is broken.’”

While she doesn’t rely on words to tell this story, sound plays an integral role in the film: calls to prayer, monks chanting, different languages being spoken (and not translated), kids playing, school bells ringing.

While she doesn’t rely on words to tell this story, sound plays an integral role in the film: calls to prayer, monks chanting, different languages being spoken (and not translated), kids playing, school bells ringing.

“My film invites audiences to sit with what is unknown, different, raw or only partially visible,” says Ignagni. “To me, a mosaic captures perfectly the subtle tensions one finds on No. 5 Road, where custom and ritual, language and cultural diversity are practised under surveillance cameras and behind locked doors and gates. In making this film, I am asking audiences to look with open eyes and hearts – with a spirit of curiosity – at themselves and their neighbours, and simply reflect on multiculturalism as an unfinished project in need of attention in Canada and around the world.”

In addition to RJDS and Az-Zahraa, the list of participating neighbours includes the Evangelical Formosan Church of Greater Vancouver, India Cultural Centre of Canada/Gurdwara Nanak Niwas, Kingswood Pub, Lingyen Mountain Temple, Mylora Executive Golf Course, Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Richmond detachment), Thrangu Tibetan Buddhist Monastery, Trinity Pacific Church, and Vedic Centre.

At VIFF, Ignagni will participate in one of a series of panel discussions presented by Storyhive on Totally Indie Day, Sept. 28, at Vancity Theatre. She will be on the hour-long panel called Not Short on Talent: The Rise of the Short Form Documentary, which starts at 3:45 p.m. For the full film festival lineup, including, eventually, the not-yet-listed screening time of Highway to Heaven – which was an Official Selection at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival – visit viff.org.