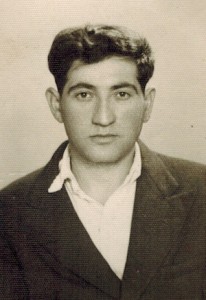

Filmmaker Haya Newman’s father Ozer Fuks grew up in Wolbrom, Poland. He escaped the town in 1939. (photo from wolbrom.pl)

The town of Wolbrom, Poland, had a population of around 10,000 in 1939; about half of the residents were Jewish. Because it was very close to the German border, it was occupied on the day the Second World War began with the invasion of Poland on Sept. 1, 1939.

Haya Newman, a Vancouver teacher of Yiddish and now a filmmaker, has spent the past several years investigating what happened to the Jews of Wolbrom. On April 14, the evening before the community gathered to mark Yom Hashoah, Newman premièred her documentary Wolbrom: My Father’s Hometown in Poland before a packed audience at Temple Sholom.

Newman’s father, Ozer Fuks, came from the town, and trouble began well before the invasion of the Nazis. When Ozer was 4 years old, his father was murdered in front of his leather goods shop. In 1939, Fuks was in the Polish army and he managed to escape the Nazis through the Soviet Union.

The project of assembling information on her father’s hometown began from almost nothing, given that her late father kept his past during the Holocaust secret.

In her attempts to gather information, Newman visited the few remaining members of her father’s family in Israel. When that branch of the family opted to leave Europe for Mandate Palestine, Newman said, the remaining family told them they were crazy, heading to a barren desert. They are the only members of her father’s family that survived.

Newman’s documentary, which was filmed by her husband, Tim Newman, follows her first to Israel and then to Wolbrom, in search of the missing pieces.

The outline of the story of Wolbrom’s Jewish residents is similar to that of Jews in thousands of other Polish villages, towns and cities.

The Jewish residents were rounded up by the Nazis and their collaborators. Some were shot on the spot while the rest were forced on a six-day march that circled back to the same town. The able-bodied who survived were forced into slave labor.

In 1941, about 8,000 Jews from the surrounding area were forced into the ghetto in Wolbrom. Eventually, some were transported to concentration camps. But most of them met a grisly fate closer to home.

A memorial was erected in 1988, apparently by residents of Wolbrom themselves, remembering the 4,500 Jews killed and buried in mass graves outside the town.

“This must be carved in Polish memory as it is carved in stone,” the memorial reads in Polish.

Walking to the site, Newman ran into locals who shared some of the stories that had come down from the older villagers.

Three holes were dug in a clearing, they said, and planks were placed across them. The Jews were ordered to undress and as they individually walked across the planks, they were shot and fell into the ravines. When the dirt was pushed over the bodies, one local recounted, the earth cracked from the movement of those still alive.

A story survives of a boy who did not. A youngster managed to escape through the forest as the murdering was going on. Police chased after him, calling out to local boys who were tending cows to catch him, which they did. An officer stood on the boy’s hands and shot him point blank.

Wolbom’s synagogue was turned into a pile of rubble during the war. The Jewish school is now an agricultural supply store – with Nazi graffiti covering the doors. While Newman said she was largely greeted with warmth during her visit, which took place in 2005, she sensed some defensiveness among Poles.

“The fact of the matter is that 90 percent of Polish Jews were killed and a lot had to do with the Polish population,” she said, adding that hundreds of Jews who had been in hiding and survived were killed after the war by Poles. There are 327 documented cases of killings, either individual murders or in pogroms in the immediate aftermath of the war, but estimates are that as many as 2,000 Polish Jews who survived the Holocaust were murdered after liberation.

The reactions from some of the locals caught on video are intriguing.

“There is nothing to look for,” said one man, “You can’t turn back time.”

Another told her, “Take it easy, it’s all in the past.”

Newman visited the home where her grandmother had lived and the woman who resided there at the time was somewhat nonchalant about the property’s provenance.

“When we bought the house, it was empty,” she said.

Other residents spoke of the horror and upset felt by non-Jewish people at the fate of their Jewish neighbors. One woman said her mother picked up Yiddish playing with the Jewish kids in town before the war. Others provided helpful information to direct Newman to the relevant sites of the former Jewish community.

Overall, the people of Wolbrom were open and very willing to speak with her, she said. “It seemed like they were waiting for me there.”

It has been 10 years since the trip that formed the backbone of the film and Newman noted that it is not only the survivors who are passing away, but the eyewitnesses who can add to the fullness of what happened during that period.

“Within five, 10 years, they are not going to be there anymore,” she said.

Rabbi Dan Moskovitz spoke after the screening and referenced the just-ended Pesach holiday to emphasize the need to tell the stories of the more recent past. Just as the Hagaddah marks the narrative of the Exodus, he said, today’s generation should be recording the narratives of this era.

“We need to tell our stories so our children can tell them the way we tell the Hagaddah,” he said. “Go home, write down and tell your story.”

Newman’s next projects include a documentary about Yiddish on the West Coast, a film about her mother’s hometown in Poland and another about Vancouver singer Claire Klein Osipov.

Pat Johnson is a Vancouver writer and principal in PRsuasiveMedia.com.