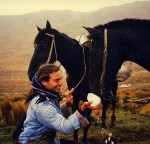

Avie Estrin in Colombia. (photo from Avie Estrin)

On Dec. 4, Avie Estrin’s solo show Blessed People opened at the Sidney and Gertrude Zack Gallery. Many of Estrin’s photos are taken in far-away places. There are Tibetan lamas gardening and a Yemenite bride in her fantastic headgear. An old man in a turban looks as if his perceptive eyes can see straight into your heart. A group of yeshivah students dance in the street. A young girl peeks out from behind a large heavy door. The door is ajar, and only fragments of the girl’s face are visible, but there is joy in her curious eyes. She has escaped her handlers, if only for awhile, and relishes her fleeting moments of freedom. Each picture tells a story.

In an interview with the Independent, Estrin talked about his life with photography, its challenges and rewards.

JI: What prompted you to mount an exhibit of travel photos? Do you shoot photos locally?

AE: Interesting question. I never understood this exhibit as a travel theme per se. While there are images from everywhere, a good number are taken right here, in Vancouver and the Lower Mainland. On the other hand, if “travel” is what others see, I’m OK with that. I can’t dictate what the show is about, since in the end it’s about what you see, not what I think I saw. I would only say that for me, it’s about real people, it’s about real life. It’s about all of us.

JI: Tell me about this show.

AE: The photos span from the early ’90s to as recently as six months ago. Photos were taken with an array of different cameras, from an old-fashioned SLR to early digitals, but nothing more modern than 2004. While I was always very particular about quality, my equipment is modest and minimal.

Photos range from hiking the Himalayas to horse trekking the Andes and Amazon basin, to more domestic venues right here in Vancouver. I could go on about harrowing experiences forging flooded rivers on horseback in Ecuador or negotiating at gunpoint with Colombian guerilla in the outback. While it makes for great storytelling, the real point is that, by and large, my experiences were joy-filled encounters with gracious peoples from across cultures, people who embraced me, brought me into their homes and shared with me the little they had. I hope the exhibit illuminates this sentiment in some small way.

JI: What do you look for in a frame?

AE: Whatever the subject, I am looking for what is essential to it. I don’t for a moment deceive myself that whatever I am experiencing in a given moment can be accurately represented or reproduced in a static concrete format … with any degree of authenticity. But if I can capture just a fragment of whatever the catalyst in that ephemeral moment, that indefinable but quintessential essence of a thing, then maybe I have done it some justice.

JI: Is there a connection between photography and your profession?

AE: It’s been said before, “all things are connected.” When we attempt to compartmentalize our lives, we are merely hanging veils between our bedrooms. The common thread is not so much what we do but how we do it.

JI: You write poetry, too. Are your poems and your photos linked?

AE: To answer this question I would simply recommend going to the exhibit, seeing the work, reading the poems, and then you decide.

JI: Do you ever use Photoshop?

AE: Photoshop? What’s that? Seriously, without getting too technical or mundane, there is no such thing as “untouched” digital photography. The moment you take a jpeg image with your point and shoot, your camera’s firmware is instantly doing a circus act to compress that eight mega-pixel shot you took down to a one or three megabyte image. Aside from losing at least 60 percent of the original image data, you are also letting your camera indiscriminately dictate what 60 percent to throw away. Even in raw format, there is no getting away from post-processing. For better or worse, the days of “untouched” photography are gone forever.

JI: Do you give copies of your photos to your subjects and, if so, do you offer them free of charge?

AE: Various images in Blessed People were taken in the pre-digital era, so showing people immediate results was in many cases not an option. I had a strict practice of sending people hard copies of their images, but often practicalities. such as remoteness, non-existent postal services, etc., didn’t allow for this either. As to charging people for the privilege of capturing their image … isn’t there something in halachah against that? There should be.

JI: What are the biggest challenges and rewards of your work?

AE: I have no idea what a real travel photographer does. For me though, doing is reward in and of itself. Doing without intentionality isn’t “doing” at all. It’s merely a happening. And intentionality implies challenge; otherwise, it would be a redundant endeavor. I love challenge. I love to do.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at olgagodim@gmail.com.