Twenty years in the making, Egypt’s Grand Egyptian Museum is in a soft-opening period, with a section of the 81,000-square-metre site open for limited guided tours. (photo from Grand Egyptian Museum)

In biblical times, the Patriarch Jacob led his family to Egypt, the granary of the ancient Near East, to escape famine in Canaan. By the Roman era, the Nile River Valley and Delta – enriched by the Nile’s annual flooding with alluvial mud – had become the breadbasket of Rome. King Herod built an artificial harbour at Caesarea to facilitate the crucial maritime shipment of wheat to the imperial capital. Today, the once fabulously wealthy country is an economic basket case.

President Gen. Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and his military-industrial kleptocracy blame the country’s high birth rate for the inability to feed Egypt’s burgeoning population of 110 million people. Taking a page from Keynesian economic theory, the regime – which toppled Islamist leader Mohamed Morsi in a 2013 coup d’état – has triggered a free fall of hyperinflation and devaluations while building mega-projects to stimulate the country’s broken finances.

The country’s annual rate of inflation soared to 36% in February, the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) said on March 31. The Egyptian pound, called the guinea, traded at 20 to the American dollar as recently as 2020. Now, one needs 52 to buy a greenback in the flourishing parallel market. In the past 24 months, a crippling shortage of foreign currency has caused prices of goods and commodities to more than triple, forcing low- and middle-income Egyptians to further tighten their belts.

The result? Strained services, a bloated bureaucracy, a huge government budget and a staggering deficit.

Compounding the economic misery, Hamas’s Oct. 7 attack on Israel and the resulting Israel-Hamas war in Gaza have driven away tourists from the land of Pharaonic wonders and spectacular coral reefs. Houthi rockets targeting shipping in the Red Sea have shrunk revenue from the Suez Canal, which is down 40% this year versus the same period in 2023. And Russia’s invasion of Ukraine two years ago has driven up wheat prices and made subsidized bread – a staple for most Egyptians – more costly.

Notwithstanding Egypt’s inability to repay its current foreign debt of about $165 billion, el-Sisi’s immediate financial problems were eased in recent weeks thanks to a bailout, more than $23 billion provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the European Union.

At the same time, the United Arab Emirates launched a rescue plan to prop up its ally through the Ras el-Hekma deal announced last month. The vast real estate project envisions a new city on the barren shores of the Mediterranean Sea near the site of the pivotal Second World War battle of El Alamein. It was concluded in exchange for $24 billion in cash liquidity and $11 billion in UAE deposits with the Central Bank of Egypt, which will be converted into Egyptian pounds and used to implement the project, reported Reuters.

Where then has Egypt invested, or perhaps squandered, its largesse?

One expensive pet project has been to expand the quasi-governmental Egyptian Railway Authority’s network of standard-gauge train tracks. The system, the oldest in the Middle East, dating back to the 1854 line between Alexandria and Kafr el-Zayyat on the Rosetta branch of the Nile, now extends across 10,500 kilometres. A further 5,500 kilometres are currently in construction, including high-speed lines from Alexandria west to Mersa Matruh, Cairo south to Aswan, and Luxor east to Safaga via Hurghada.

Equally ambitious are plans to expand the country’s clogged highways. Transportation Minister Kamel al-Wazir, who took over the accident-plagued portfolio from Hisham Arafat following the 2019 Ramses Station train disaster, in which 25 Cairenes were killed and 40 injured, plans to complete 1,000 bridges, tunnels and flyovers this year.

Key to the plan to clear Cairo’s traffic woes is to complete an ambitious, shimmering new capital 50 kilometres east of the megalopolis, whose population is estimated to be more than 22 million people. The so-far-unnamed New Administrative Capital, under construction for nearly a decade, is located just east of the Second Greater Cairo Ring Road. It includes more than 30 skyscrapers, the most striking of which is the 77-floor Iconic Tower – the tallest building in Africa. Equally noteworthy are the 93,000-seat soccer stadium, the Fattah el-Aleem Mosque, accommodating 107,000 worshippers, and the Nativity of Christ Cathedral, which has room for 8,000 Copts.

To date, 14 ministries and government entities have relocated to the New Administrative Capital, but the city remains a largely lifeless white elephant with few residents.

Apart from these vast infrastructure projects, Egypt has been burnishing its cultural heritage. In 2022, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquity launched the Holy Family Trail, stringing together some 25 stops along the celebrated route that Jesus, Mary and Joseph took to escape King Herod’s wrath. Last year, the government restored the medieval Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fostat (Old Cairo), the home of the Cairo Geniza. The long-delayed Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza near the Pyramids is scheduled to officially open this summer – though no date has been announced.

Twenty years in the making, the GEM is currently in a soft-opening period, with a section of the 81,000-square-metre site open for limited guided tours.

Touted as the largest archeological museum complex in the world, the GEM will house more than 100,000 artifacts. It will showcase the treasures discovered in the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922. Other highlights will include a restoration centre, an interactive gallery for children and the Khufu Boat Museum.

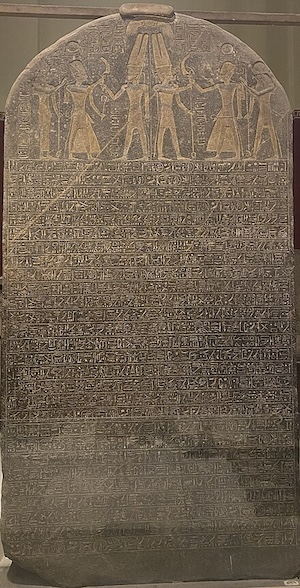

King Tut’s funerary possessions had been on display at downtown Cairo’s Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square, a hopelessly inadequate leftover from Britain’s colonial rule. There, a decade ago, I wandered in sensory overload gawping at the Aladdin’s Cave of Wonders. As if guided by divine providence, or perhaps Ra or Isis, I stumbled upon the Merneptah Stele – a three-metre-high piece of black granite inscribed by the New Kingdom pharaoh, dated around 1208 BCE, which was discovered in Thebes in 1896 by archeologist Flinders Petrie. Line 28 reads: “Israel is laid waste – its seed is no more.”

For me, it symbolizes the cold peace Israel and Egypt have enjoyed since 1979. Though few Israelis would wish to repudiate that historic agreement, many share the sentiment of Eitan Haber, the confidant of former prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, who said: “The Egyptians don’t like us and – why deny it? – we don’t like them.”

Gil Zohar is a writer and tour guide in Jerusalem.