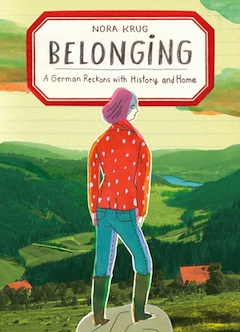

Nora Krug’s Belonging offers a thoughtful and artistic exploration of identity and history. (photo by Nina Subin)

Nora Krug’s Belonging: A German Reckons with History and Home (Scribner, 2018) opens with a page made to look like it’s written in pencil on yellow graph paper. The illustration of a bandage takes up half the page, which is ostensibly “From the notebook of a homesick émigré: Things German.” Entry No. 1 is about Hansaplast, a type of bandage created in 1922 that Krug associates with safety, her mother having used it, for example, to stop Krug’s knee from bleeding after a roller-skating accident at age 6. “It is the most tenacious bandage on the planet,” writes Krug, “and it hurts when you tear it off to look at your scar.”

Belonging is the written and illustrated account of what happens when Krug decides to rip off the Hansaplast and examine the scars left by the history of her family – which had only been related to her in vague terms – and her country of birth, Germany. It is a creative and engaging memoir about Krug’s efforts to define for herself and reclaim for herself the idea of Heimat, tarnished by the Nazis’ use of it in propaganda.

Heimat can refer to an actual or imagined location with which a person feels familiar or comfortable, or the place in which a person is born, the place that played a large part in shaping their character and perspective. Krug’s exploration of identity comprises archival research, interviews with family members and others, and visits to her mother’s and father’s hometowns – Karlsruhe (where Krug grew up) and Külsheim, respectively.

Heimat can refer to an actual or imagined location with which a person feels familiar or comfortable, or the place in which a person is born, the place that played a large part in shaping their character and perspective. Krug’s exploration of identity comprises archival research, interviews with family members and others, and visits to her mother’s and father’s hometowns – Karlsruhe (where Krug grew up) and Külsheim, respectively.

Alternating with the narrative of her discoveries are several notebook entries, on a range of items, from bread to binders to soap, which are both points of pride, as they are quality-made items, and metaphors. For example, Persil is “a time-tested German laundry detergent invented in 1907,” which Krug uses. However, she writes, “Some referred to the postwar testimonials written by neighbours, colleagues and friends in defence of suspected Nazi sympathizers as Persil Certificates. Persil guarantees your shirts to come out as white as snow.”

As well, Krug includes pages “From the scrapbook of a memory archivist,” which present odd and sometimes disturbing arrays of items found at flea markets on her research trips to Germany. These include Hitler Youth trading cards, a letter from the front containing a lock of hair and photographs of soldiers petting or holding various animals, mostly dogs.

But the main intrigue of the book comes from what Krug shares as she persists in her research, asking questions and scouring documents. She wants to find out all she can about her family’s involvement in the Holocaust, in particular that of her maternal grandfather, who died when Krug was 11, and her paternal uncle, who was drafted at 17 and shot and killed at age 18, before her father, a postwar baby, was born; her father was named after the brother he never knew. Despite her efforts, many of Krug’s questions remain unanswered.

At the end of Belonging, it’s not even clear if Krug – who readers find out early on married into a Jewish family – feels any less guilty or any more secure in her self and in her past. But she does manage to start the healing process on some family rifts. And she highlights a couple of steps towards healing that she witnesses in Germany. For example, of Külsheim – which had, in 1988, the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht, abandoned a proposal for a memorial plaque where the synagogue once stood, before it was burned down the night of Nov. 10, 1938 – she writes: “Plans are made to restore Külsheim’s old mikvah, and a memorial stone is erected where the synagogue used to be, ‘as a manifestation of sadness and shame,’ Külsheim’s new mayor says on the day it is installed.”

The book ends as it began, with a notebook entry. No. 8 is Uhu, “invented by a German pharmacist as the first synthetic (bone-glue-free) resin adhesive in the world, in 1932.” Despite its world-record strength, which is why Krug imports it to repair everything from the soles of her shoes to broken dishware, Uhu “cannot cover up the crack.”