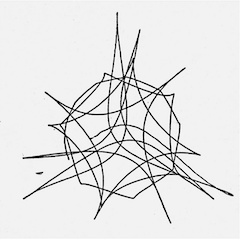

An archival photograph of Andrzej Jan Wroblewski explaining the mechanics of one of his kinetic sculptures, a predecessor of Opus 6. (photo from cicavancouver.com)

During the six decades of his professional life, industrial designer Andrzej Jan Wroblewski contributed to almost every area of artistic expression and human consumption. A list of his works includes cutlery for an airline, an excavator, tapestries, computer software, children’s books, kinetic sculptures, an iron, and a portable shower in a suitcase. His retrospective show, Andrzej Jan Wroblewski: Invisible Forces of Nature in Art and Design, opened Jan. 26 at the Centre of International Contemporary Art (CICA) in Vancouver.

Wroblewski graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, Poland, in 1958. A year before, as a student, he participated in his first major sculpture competition – for the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial. The committee received 426 entries from many countries. Wroblewski and his friend, architecture student Andrzej Latos, designed a way for a visitor to walk through the camp’s horrors, to understand them on a visceral level. Their design used the existing landscape, while the authors acted as composers of the visitors’ experience.

“Our submission was one of only seven selected for the short list,” Wroblewski said in an interview with the Independent. “Before I submitted, I didn’t even tell my sculpture professor. I thought he might have submitted his own concept and I didn’t want him to think I was competing with him, especially if I didn’t win. I was right. He did submit his own proposal and he was one of the seven shortlisted as well.”

After that, there was no more hiding. “But my professor was a wonderful man,” Wroblewski recalled. “He told me that my presentation was so good, I should use it as my diploma project. He also offered me the position of his assistant after my graduation.”

Wroblewski started teaching sculpture, but he doubted the artistic medium would be his future. “After my project didn’t win the Auschwitz competition, someone tried to comfort me,” he said. “They said I could use the idea for some other project, and it made me angry. Re-using that idea felt wrong. The whole concept was created for a special place and purpose; it didn’t belong elsewhere. And that led me to thinking that maybe sculpture wasn’t what I wanted to do. Artists rarely decide what happens to their creations; bureaucrats decide. But if I switched to industrial design, I would have many more chances to give my creations to people: industrial designers create with their users in mind.”

He switched to industrial design and became one of the pioneers in the field in Poland. He submitted proposals for several international competitions and worked on many objects on contract with production companies. An excavator, a scooter, and a set of thin steel cutlery for a Polish airline all originated from that period of his life. He became the first dean of the faculty of industrial design of his alma mater.

“Industrial design changes our behaviour,” he said. “If I design a cup and it goes into production, it could change how people drink. Good industrial design is supposed to make our lives easier.”

Wroblewski was one of the first industrial designers in Poland to use a computer, and even developed special software to help other industrial designers. By 1987, he was a rector of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Cracks in the Iron Curtain were already emerging, and the academy started cooperating with one of the best schools of industrial design in the United States. In 1988, Wroblewski received an invitation to teach at the University of Illinois.

“I taught there for 13 years, before I retired,” he said. “After retirement, in 2000, my wife and I moved to Vancouver. Our daughter was already here, working at UBC. I taught at Emily Carr, but for one semester only. I still had too many ideas, too many projects in my head, and I wanted time. Retirement gave me that time.”

Some of his ideas are on display at the CICA gallery. All of these installations employ various forces of nature, which lent the show its name. “In the past,” Wroblewski said, “the division in the arts was much more rigid. You either did sculpture or you painted or you drew. Now, the dividing lines are dissolving. The artist uses what he needs to express himself. One installation might involve several artistic forms in various combinations.”

One of the pieces is an interactive kinetic sculpture called Opus 6. It explores kinetic energy and gravity. There is a moving part with a tablet and a stationary part with a suspended pen. If you put a piece of paper on the tablet and give it a nudge, it begins swinging, and the pen produces a unique abstract drawing on the paper underneath.

For Wroblewski, Opus 6 was a reconstruction. His original installation was called Opus 5 and it was bought by a museum in Poland. “I decided it was much cheaper to build it from scratch here, in Vancouver, than to transport the original from Poland and back,” he said.

Another installation explores gravity and viscosity and concentrates on water. “I studied music before the art academy [and] I used my own music for the water installation,” the designer shared. “I also built a special maze of Plexiglass to be able to see how a drop of water flows, and then I recorded it all in a light projector and created a video. This installation is a tribute to water, one of the most powerful forces of nature.”

In a separate corner, made dim by the enclosed walls, Wroblewski situated a series of light sculptures. His chandeliers hang from the ceiling or stand on the floor, their radiance interweaving. The shapes and sizes are all different, but the material used is the same: paper-thin strips of light-coloured wooden veneer.

Wroblewski’s desire to explore new materials and new approaches for his work always drove him towards experimentation, towards the unknown. “When I came to the States, I was fascinated by computers,” he said. “I used a program called Paintbrush to create some abstract compositions, but, at that time, there were no printers big enough to give me the large size I wanted. I decided that a tapestry would be the best medium to enlarge those digital paintings. I built a special loom and made a tapestry for each of those paintings. Every pixel in the digital paintings corresponds exactly to one knot in the tapestry. It took me about six months to complete each of the large tapestries. It is how I operate. When I have an idea, I find a way to achieve it.”

Demonstrated side by side with the printouts of his digital paintings on standard-sized paper, his couple-metre-wide tapestries look impressive.

One of his most recent projects is a series of 10 children’s picture books. Each book is about a specific animal, with the amusing pictures by Wroblewski and the text by his daughter, University of British Columbia professor Anna Kindler. “We did it when my great-granddaughter was born, three years ago,” he said.

His latest sculpture dates from about the same period, 2019. “I saw a tree grown through a fence, as if the wires sprouted from inside the tree. It was near UBC. I cut it down and installed it in a wooden frame. It demonstrates how nature could absorb civilization.”

In 2018, for his lifetime contributions to the field of industrial design in Poland, Wroblewski was awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland. He was also named one of the three most influential Polish designers of the 20th century.

The retrospective runs until March 3. For more information, visit cicavancouver.com.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected].