It’s a wonder any of us are alive. And it’s even more a wonder that we are each the result of generations (not to mention stardust). Not only do genes past and present influence who we are, but the actions of our ancestors, both distant and recent, brought us to where we are today. And we are but a moment in time, a link to future generations.

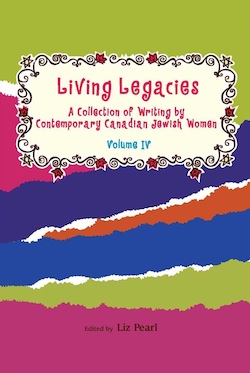

It’s hard not to get sentimental and contemplative reading Living Legacies: A Collection of Writing by Contemporary Canadian Jewish Women (PK Press, 2014). In this instance, Volume 4 that Toronto-based editor Liz Pearl has brought to life; though the previous editions are equally thought-inspiring. Volume 5 is already well in the works.

Among the more than 20 contributors to Volume 4 is Pearl with an essay on her name, Lisbeth Anne Ahuva Pearl Katz, though she has been known as Liz since 1990 and rarely uses her husband’s surname. “I have always liked the name Pearl – a rare and precious gem, and have never considered it just my maiden name,” she writes. “Pearl is a central piece of my name and core identity.” As is her namesake, her maternal great-grandmother Liba Sherashevsky Gitkin, z”l. Born in Lithuania, Liba and her family all died in the Holocaust; her grandmother, Sonia bat Liba, “managed to emigrate in 1935 [to Canada], following a brief courtship and quick marriage” – “the sole surviving member of her family-of-origin.”

Among the more than 20 contributors to Volume 4 is Pearl with an essay on her name, Lisbeth Anne Ahuva Pearl Katz, though she has been known as Liz since 1990 and rarely uses her husband’s surname. “I have always liked the name Pearl – a rare and precious gem, and have never considered it just my maiden name,” she writes. “Pearl is a central piece of my name and core identity.” As is her namesake, her maternal great-grandmother Liba Sherashevsky Gitkin, z”l. Born in Lithuania, Liba and her family all died in the Holocaust; her grandmother, Sonia bat Liba, “managed to emigrate in 1935 [to Canada], following a brief courtship and quick marriage” – “the sole surviving member of her family-of-origin.”

About to volunteer as a chaperone on a March of the Living trip, Pearl reflects on the “strong values of Zionism, Yiddishkeit, tzedakah and Jewish education that were central” to her grandmother’s life, which she gained from her mother and others of that generation, and which she passed on to her children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and counting. “My namesake and maternal lineage are firmly embedded with history, heritage and wisdom, and form the roots of my solid Canadian Jewish identity.”

Other contributors echo these types of thoughts and feelings. Local author Lillian Boraks-Nemetz, a child survivor of the Holocaust, dedicates her essay, called “Sacrifice,” to her “beloved grandmother, Kazimira Solomon Boraks (1878-1949).” Describing a moment in Russia in the summer of 2010, she writes, “I stand on the shore of the city of the Bronze Horseman, searching the horizon, scanning it for clues to a woman who was born here long before the city became Leningrad, who spent her life in exile, and who died in exile, away from her homeland and her family. A woman who saved my life – my babushka, grandmother in Russian.”

Boraks-Nemetz briefly recounts some of her memories of her years in hiding, the physical and emotional effects of what she experienced and witnessed, her grandfather’s death in the ghetto, and her father’s death only weeks before her grandmother’s in 1948. She notes some of the similarities in their lives – hers and her grandmother’s – and she explains the sacrifices her grandmother made to keep her alive. It is a loving and moving tribute.

Each essay in Living Legacies has something to recommend it. Not all are as deeply serious but all are personal, yet universal. Gratitude is one of the words that comes to mind after reading this collection. Looking at life in the context of the generations before and still to come is both humbling and empowering.