This month – and in this issue – we celebrate Israel. Few regular readers would disagree with the assertion that the state of Israel represents a modern miracle. For whatever criticisms are fairly and unfairly leveled at Israel and its governments, this tiny country, populated mostly by refugees and their children, has accomplished and built one of the greatest societies in the world in what is, by historical standards, a blink of an eye.

There are so many quantitative examples of Israeli achievements: per capita numbers of Nobel prizes and other recognitions of achievements, world-leading academic publishing, number of businesses launched and successes reached, diverse and life-altering scientific breakthroughs and exceptional contributions across almost every discipline of human endeavor.

Then there are the incalculable measurements that are what strike so many of us when we visit Israel – or when we are visited by Israelis. In just the coming weeks alone, we are offered numerous samples of the cultural richness of the country.

The community-wide Yom Ha’atzmaut celebration on April 22 features Micha Biton, whose music is an example of the beauty that can emerge even in places and times of challenge, he being a part of the music scene in Sderot. A week-plus later, we will be treated to Ester Rada, an actress and singer who just emerged on the international scene.

These are just two of the most immediate examples of Israeli culture offered to local audiences year-round, including an embarrassment of riches during festivals like Chutzpah!, the Jewish book and film festivals, and during regular programming at the J. Israeli artists and photographers are regularly featured, as are speakers on diverse topics, brought here by local affiliates of Israeli universities and institutions.

To say that we – even 10,000 kilometres away – are enriched by the abundance of culture and knowledge that defines Israel is to underestimate the blessing it is to us. But this is not a one-way relationship. There is a greatness, too, in the way our community has mobilized for seven decades to help Israelis flourish. These bilateral connections are deep and important. From the moment the state of Israel was proclaimed 67 years ago, Vancouverites have been integrally involved with Israel in countless ways.

Before intercontinental travel became commonplace, stories appeared in the pages of this newspaper about locals traveling to Israel – as tourists, as volunteers, as dreamers seeking to see in their lifetimes the reality of a revived Jewish nation. More common still was the plethora of organizations emerging to assist in the nurturing of Israel through acts of tzedaka and volunteerism here at home. Women’s groups, youth movements, Zionist agencies of all stripes, “friends” of universities and hospitals, and so many other great institutions popped up, mobilized by the passion local community members felt for the rebirth of the Jewish nation.

Though these connections have changed, they have not diminished. Thanks to improved technologies and transportation, our community sends athletes to meet and compete with their Israeli cousins – and welcome Israelis here in return. We continue to support so many projects and institutions in Israel that “Vancouver” and local family names proudly adorn countless buildings, facilities, medical machinery, ambulances and other resources in Israel.

In a world that sometimes seems mad to us (as well as mad at us), there are few in our community who take for granted the blessing that Israel is to us and to the world.

As we celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut this year, marking Israel’s 67th anniversary, let’s make a commitment to ourselves, a new year’s resolution of sorts for Israel’s new year.

Let’s be even more conscious of our relationship with Israel. Let’s go out of our way to buy Israeli products and support Israeli initiatives. Find an Israeli cause you haven’t yet supported – there are plenty of advocates right here in town for universities, charities and other great projects – and make it one of your causes. Take more of the opportunities offered to us throughout the year as Israeli speakers, performers and artists visit. Head to the Isaac Waldman Jewish Public Library and learn about an aspect of Israel that’s new to you. Watch more Israeli film. Take Hebrew lessons. The options are endless without even leaving the comfort of your hometown.

If you can, of course, travel to Israel. An “on-the-ground” education is invaluable. One of the best ways to express your curiosity, and support Israel is to spend time there, meeting Israelis, investigating for yourself aspects of Jewish history and culture, experiencing new tastes, sounds, smells and sights. And, while you’re there, open your heart and mind to the realities of this great country; pledge to learn more about the land, its people, its creatures, its ecology, the good, as well as the more challenging aspects that could use some work. Pack up the family, join a community mission or grab a backpack and head over on your own – the mishpacha is waiting for you.

Happy birthday Israel and moadim l’simcha.

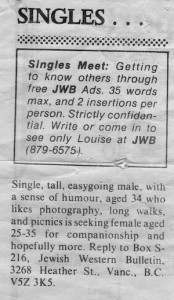

Ron Freedman, who passed away in December 2014, worked for the Jewish Western Bulletin / Jewish Independent for 46 years. As we mourned his loss with his family at a ceremony celebrating his life, his son David shared the story of how his father and his brother Steve, who has worked at the paper for more than 30 years, used the power of community media to change his life.

Ron Freedman, who passed away in December 2014, worked for the Jewish Western Bulletin / Jewish Independent for 46 years. As we mourned his loss with his family at a ceremony celebrating his life, his son David shared the story of how his father and his brother Steve, who has worked at the paper for more than 30 years, used the power of community media to change his life.