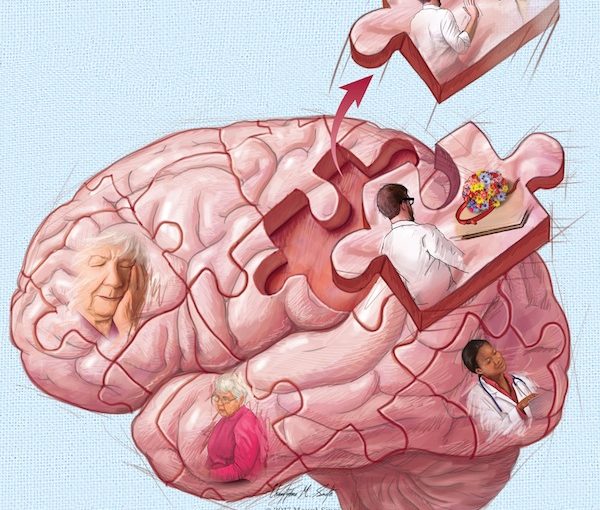

Israel’s Lavi furniture factory recreated Carlebach Synagogue’s original ark from three prewar black-and-white photos. (photo from IMP)

Viewing the restored Carlebach Synagogue in Lubeck, Germany, brings to mind the biblical prophecies of consolation, where the Jewish people are reassured that the day will come when not only will they be restored to their land, but their houses of worship will likewise be restored. Sadly, neither the shul’s rabbi nor any other of the original community members are alive today to revel in the synagogue’s reinstated glory; however, in an interesting twist, several of the rabbi’s grandchildren are the children of founding members of Kibbutz Lavi, whose furniture factory designed and built the synagogue’s ark and other holy articles.

Rabbi David Alexander Winter, rabbi of the Carlebach Synagogue, fled Lubeck in 1938, together with most of his community. Several months later, on Kristallnacht, when many of Germany’s synagogues were torched and burned to the ground, the Lubeck shul was damaged and looted, but not destroyed – the building had been sold to the municipality and the contract, signed by the rabbi, was inside the synagogue, in plain view.

For Winter’s grandchildren, seeing the restoration of their grandfather’s synagogue is especially moving. “It’s a feeling of coming full circle,” said Yehudit Menachem, who visited Lubeck last year, seeking to learn more about her family history. Dr. Ariel Romem, a pediatrician and one of the grandsons, remarked that the restoration is symbolic of the re-blossoming of the Winter family and of the Jewish people as a whole. “They may have ruined the shul, but they never succeeded in breaking us,” he said.

In the seven decades since the Holocaust, the once-stately synagogue, established in 1880, has suffered looting, a firebombing, squatters and general neglect. German architect Thomas Schröder-Berkentien began working on its restoration in 2010, but the project was stuck due to a lack of funding. In 2016, the federal government dedicated a sizable sum, with other funding arriving from the Schleswig-Holstein state, the Lubeck-based Possehl Foundation and UNESCO, which had declared the Old City of Lubeck a World Heritage Site. The total cost of the project amounted to almost $10 million.

Schröder-Berkentien was intent on finding the best craftspeople for the synagogue furniture, and also felt that it was only right that the furniture should come from Israel. He found the Lavi furniture factory online and, after several inquiries and a visit to the carpentry workshop along with his team, was assured that they had the necessary experience and expertise to perform the research and produce items of quality and beauty. Indeed, in its 60 years of operation, Lavi has designed and produced interiors for synagogues in more than 6,000 Jewish communities around the world, including for new and restored synagogues in Germany.

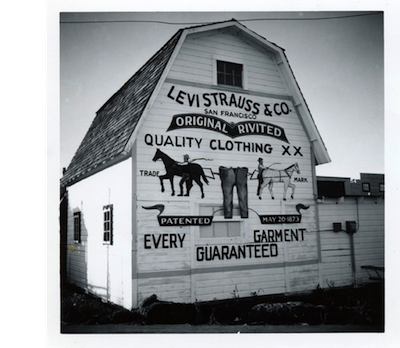

Motti Namdar, the factory’s chief planner, described the challenge, and ultimate satisfaction, of creating replicas of the original items. “We only had three prewar black-and-white photos to go by,” he explained. “The photos showed only one angle and even that was not very clear. It was difficult to make out a lot of the detailing or which metals were used, especially for the ark, which you can see from the photos is very unusual.”

Ultimately, much of Namdar’s work had to be done by deduction and a knowledge of the history of the period. “I traveled to Lubeck to see the synagogue and examine the parts that had not been damaged. Part of the ladies’ gallery was intact. The architect had hired restoration experts who carefully removed the layers of paint from the walls, exposing the original murals. The synagogue as a whole had been built in the Moorish style, and I proceeded in that direction.”

In one of the photos, it’s possible to make out the pointed roof-like structure at the top of the ark, which Namdar designed to include 1,500 “scales,” all coated in pure gold. Under Namdar’s direction, the Lavi factory completed all the articles by the deadline. “The hardest part wasn’t the tight schedule, but, rather, building everything such that it could be taken apart, packed and shipped, and then reassembled so that everything fit perfectly.”

But while it was clear to the craftspeople at Lavi that they wanted to produce replicas that were as authentic as possible, the project’s architect, Schröder-Berkentien, was intent that the structure itself, which was restored to be a national monument, should serve as a testament and, in his words, “like a wound,” as a painful reminder of the events of 1938. This was the reasoning behind his decision not to redo the synagogue’s original ornate façade, which, together with the cupola and other elements, had been destroyed on Kristallnacht. “The plain red brick tells the story of what happened,” he said. “A rebuilt façade would ignore that part of history, failing to show the suffering of the era. This is what makes it such a unique monument among other German synagogues.”

When news of the coronavirus pandemic first broke in January, the factory began working overtime so that everything would be ready for the gala re-inauguration, which was to have been attended by high-ranking German officials, including Chancellor Angela Merkel, members of the restoration committee and local community figures, as well as Winter’s grandchildren from Kibbutz Lavi. However, when it was finally time for the assembly and installation of the furniture, the world was already in COVID-19 lockdown. As soon as it was possible, Lavi sent their own experts from England to complete the work. Now, the synagogue stands in all its resplendent glory, but the ceremony has been postponed indefinitely.

The important thing is that the synagogue is open and operating, serving as a spiritual hub for Lubeck’s 700-strong Jewish community. “This synagogue is not only a place of prayer, but a symbol of the revival of Jewish life in Lubeck, throughout Germany and around the world,” said the current spiritual leader of Lubeck, Rabbi Nathan Grinberg.

– Courtesy International Marketing and Promotion (IMP)