(photo by Mark Binder)

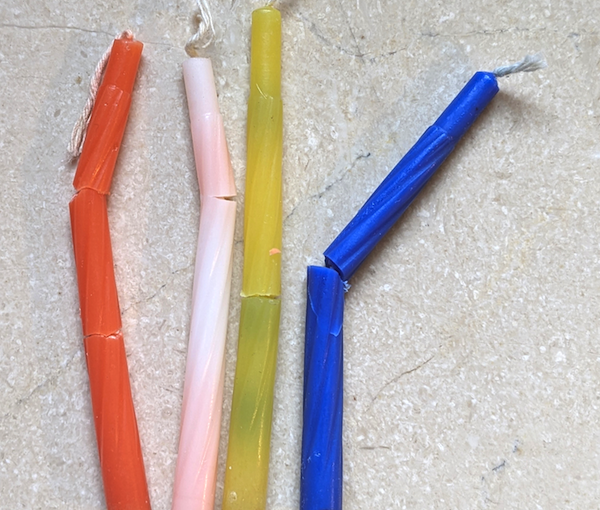

Rachel Cohen stared at the full box of candles. Since her parents had separated, getting ready for Hanukkah wasn’t the same. Four candles were broken. Of course.

She chewed on her lower lip.

In the old days, her family had gathered around the kitchen table, and argued about who would light the shammos and who would light the first candle.*

“You did it last year,” her twin brother Yakov always insisted.

“No,” Rachel would counter. “I lit the shammos, which is better.”

“No, it’s not. The first candle is best.”

“Children, hush,” their mother, Sarah, would say as she flipped a potato latke. “You’ll disturb your father.”

Their father, Isaac, would be looking at his little book, pretending to mumble prayers, while holding back a smile.

The compromise was always the same. Rachel would light the shammos, which was better, and Yakov would light the first candle, which made him happy, too.

This year, her parents lived in different houses, and Hanukkah wouldn’t be the same. Rachel didn’t know what to do. She felt small, helpless and embarrassed.

In the village of Chelm, 12-year-old Rachel Cohen was known as the smartest young girl, someone whose wisdom was both sought after and respected.

“If you don’t know what to do,” everyone said, “ask Rachel Cohen, and whatever she says, do that!”

Rachel knew that she wasn’t really that brilliant. But whenever someone asked her a question, she either had the answer, or knew how or where to find it.

“The secret of being wise,” Rabbi Kibbitz had once taught her, “is to listen quietly for as long as you can without saying anything. Ask a few questions, and then nod your head and wait until the answer arises. Most of the time, they’ll think of it themselves, and then give you all the credit.”

Rachel nodded her head and asked herself, “But what does a so-called wise person do, when they don’t know the answer?”

She looked around the kitchen, which was also silent.

Then it came to her, and she smiled.

* * *

The bell over the door to Mrs. Chaipul’s restaurant rang and, without looking up, the elderly woman behind the counter told Rachel, “Your mother’s gone to the market in Smyrna to get potatoes for the latkes.”

“Can we talk?” Rachel asked quietly.

Mrs. Chaipul glanced at the young girl, nodded her head and shouted, “All right, the restaurant is closed until lunch for a health and safety inspection!”

Most of the men finished drinking their tea or coffee, put on their coats and headed to the door.

Reb Cantor the merchant didn’t budge. “I thought you already paid the health and safety inspector.”

“This is for your health and safety,” Mrs. Chaipul told the merchant. “Because I won’t guarantee it if you stay.”

Reb Cantor smiled, stood and kissed Rachel on the top of her head as he left the restaurant.

Mrs. Chaipul locked the door behind him and led Rachel to the table in back, where she’d already placed two cups of hot herbal tea.

The young girl and the old woman sat across from each other, lifted their cups at the same time, and blew.

* * *

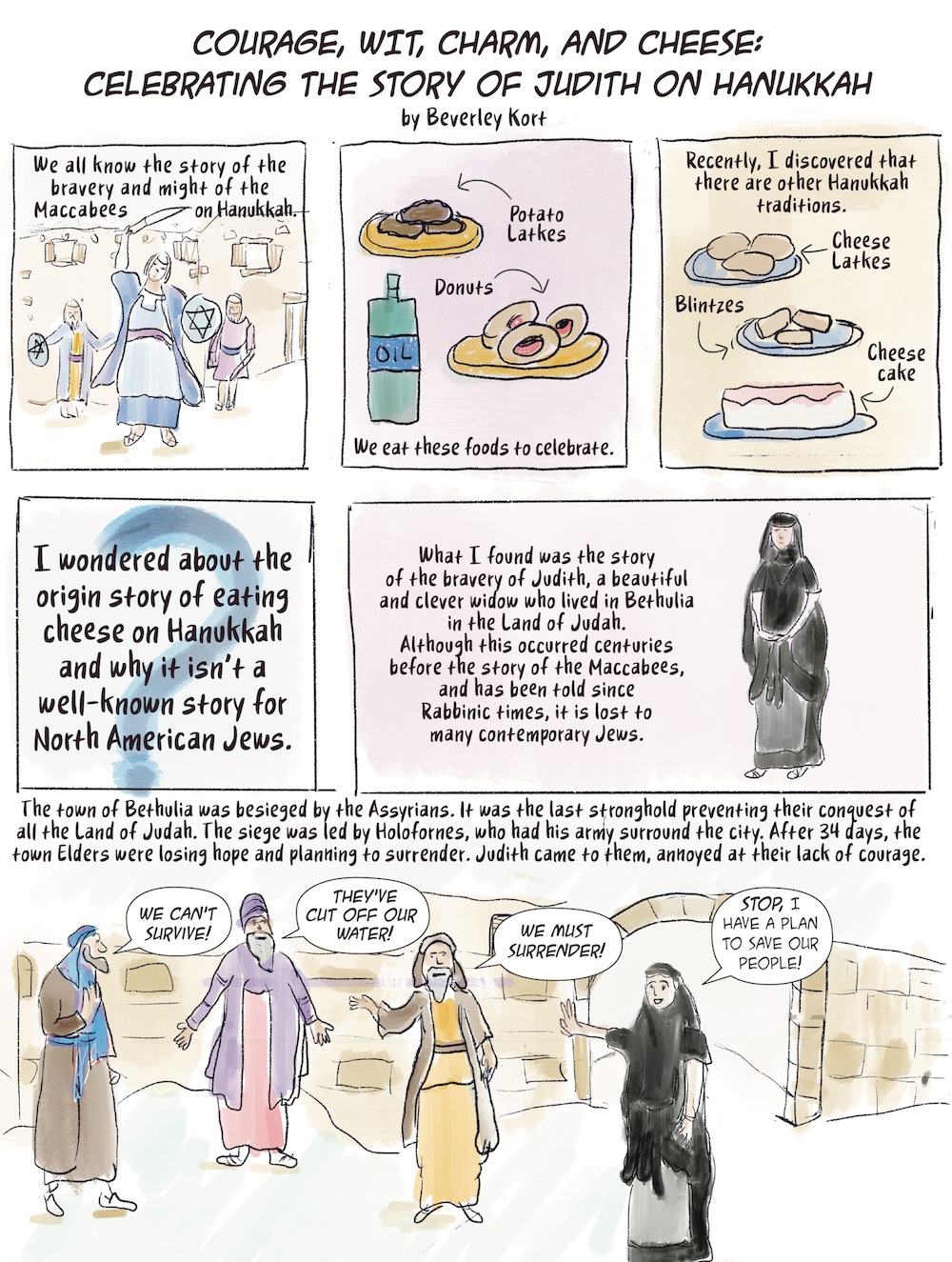

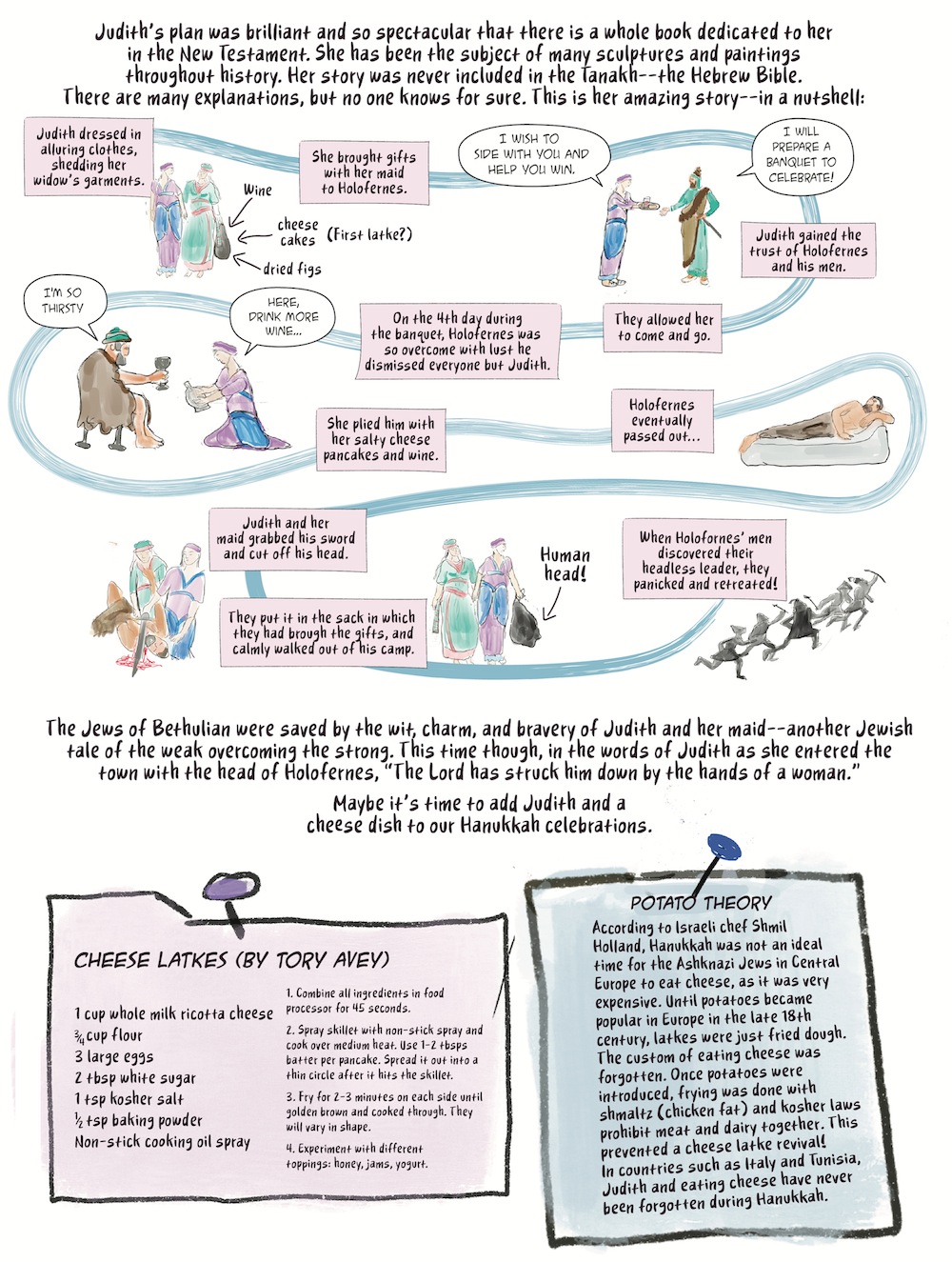

Mrs. Chaipul listened as Rachel explained, “On the first night of Hanukkah, our family starts with eight candles ablaze, and then we light one fewer each night. This, my father says, echoes the Maccabees’ fear that the oil in the eternal light might burn out at any moment.

“But, on the last night, where there would only be one candle and the shammos, we changed the tradition and light all eight again. For us, the last night is a true celebration of joy. My mother says it’s just nice to have all the extra lights.

“This Hanukkah, Yakov and I are supposed to take turns, one night with Mama and the next with Papa. I want things to be the same, but no matter how hard I try to rearrange it, the number of candles always comes out uneven. Plus, four of our candles are already broken, which seems like a sign!”

Rachel waited for Mrs. Chaipul to tell her how to solve the problem. But Mrs. Chaipul didn’t say anything. She was married to Rabbi Kibbitz, and kept her own name, which is another story. She’d often chided her husband that it was better to keep your mouth shut than to put your foot into it.

Rachel sighed. She sipped her tea.

Then she smiled, and nodded. She suddenly knew what to do. “Thank you, Mrs. Chaipul. I need to hurry and buy more candles.”

Mrs. Chaipul gave Rachel a hug. “I didn’t do anything. But I wish you well.”

Rachel ran from the restaurant, and Mrs. Chaipul reopened the front door for the lunch crowd.

* * *

That year, Rachel Cohen changed their tradition again.

“Whether we are with mother or father,” she told her brother, “instead of lighting eight or seven or one, each night we will take turns lighting all eight Hanukkah candles.”

Yakov was upset. “So many candles seems wasteful. And that isn’t the way Hanukkah is supposed to be celebrated!”

“Everything changes,” Rachel said, “and it’s up to us to make it new again. This way, the time we spend together will be even brighter.”

“All right.” Yakov shrugged. “But I light the first candle.”

“You did it last time.” Rachel smiled. “But that’s fine. Lighting the shammos is better….”

Izzy Abrahmson is the author of Winter Blessings and The Village Twins. He’s also a pen name for storyteller Mark Binder. Find the books on Amazon and Audible, with signed copies and links to the audio version of this story at izzyabe.com and markbinderbooks.com.

***

*A note on candlelighting

A shammos is the candle that is used as a match to light the other candles. While most people follow the tradition of Rabbi Hillel, lighting one candle the first night of Hanukkah and then adding candles each night, the followers of Rabbi Shammai start with eight and work their way down. Rachel Cohen is not yet a rabbi, but who knows what the future will bring.

– IA