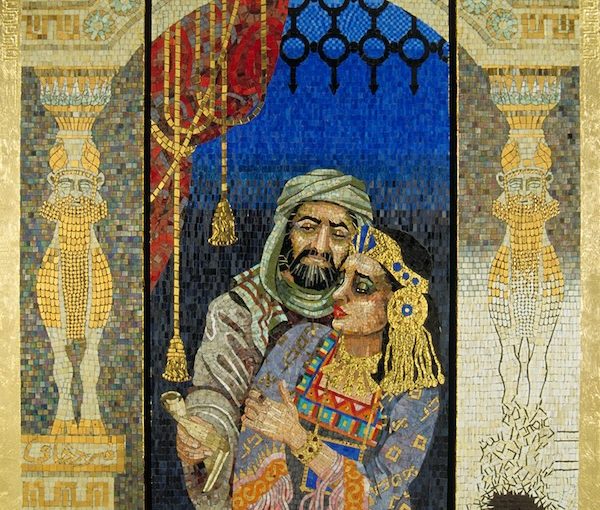

Ilan Rabchinskey’s photograph of Tamarind Street Corn Cups in Sabor Judío: The Jewish Mexican Cookbook inspired me to make them. (photo by Ilan Rabchinskey)

Since reviewing Sabor Judío: The Jewish Mexican Cookbook by Ilan Stavans and Margaret E. Boyle for the Independent’s Hanukkah issue, I’ve tried several more recipes. And I’ve really enjoyed everything. So much so, that I pulled out the cookbook to try some Passover meals, and found some foods I would never have thought to make.

Stavans and Boyle have a section on Passover (Pésaj) in which they discuss some of the Mexican Jewish traditions. For example, some families incorporate Mexican history into the seder discussions, and the bitter herbs on the seder plate can include a variety chiles. They list 12 seder favourites, but, throughout the cookbook, they point out which dishes – like Stuffed Artichoke Hearts – are considered essential components of the Passover meal by some.

Of the seder favourites, I made Snapper Ceviche con Maror, Tamarind Street Corn Cups, Apricot Almond Charoset Truffles and Tahini Brownies. The photos by Ilan Rabchinskey drew me into the corn cups, as I’m not a huge corn fan and might not have made them otherwise. I will do so again, however – they were easy, and they were a very tasty break from the ordinary. The snapper ceviche, too, will be a repeat, and the brownies were some of the best I’ve tasted, not too sweet, and very light, almost fluffy, but moist – I broke up a chocolate bar instead of using chocolate chips, which worked really well, and the sea salt on the top tasted so good. While the truffles were also delicious, they tasted more familiar, and were very date forward – I might try to mix up the date-apricot balance when I make them again.

The Jewish connections were obvious for some of these recipes, not so much for others. The snapper is served with a dollop of horseradish: “The use of maror, or horseradish, in this recipe was an invention during a Passover seder in Mexico City, creating a savoury contrast among the fish, the jalapeño and the horseradish,” write Stavans and Boyle.

The Jewish link to the corn cups is that the tamarind-flavoured hard candies the recipe calls for – Tamalitoz – were created by Jack Bessudo, who is of Mexican Jewish descent, and his husband, Declan Simmons. Since Tamalitoz are not available here, I bought another tamarind-flavoured candy from a local Mexican store and it worked quite well.

The brownies recipe comes from Israeli immigrants to Mexico, who shared with the cookbook writers that “tahini is also infused into their adaptations of mole, the sesame flavour substituting for more common varieties that rely on peanut or almond.”

Chag sameach!

SNAPPER CEVICHE CON MAROR

(serves 6; prep time 25 min plus chilling)

3/4 cup fresh lime

1/4 cup fresh lemon juice

1 small jalapeño chile, seeds removed, finely chopped

1 small red bell pepper, seeds removed, finely chopped (about 1/2 cup)

1 small yellow bell pepper, seeds removed, finely chopped (about 1/2 cup)

1 small garlic clove, minced, grated, or pushed through a press

1/8 tsp ground cumin

1/2 tsp kosher salt

1 pound red snapper fillets, skin removed

2 tbsp finely chopped fresh cilantro

1 tsp extra-virgin olive oil

prepared horseradish, for topping (optional)

1. In a large bowl, stir together the lime juice, lemon juice, jalapeño chile, red and yellow bell peppers, red onion, garlic, cumin and salt.

2 . Using a sharp knife or kitchen shears, cut the fish fillets into 1/2-inch pieces and add to the citrus mixture, stirring to combine. Cover the bowl and refrigerate for 30 minutes.

3. Just before serving, stir in the cilantro and oil. Serve immediately, dolloped with horseradish, if desired.

TAMARIND STREET CORN CUPS

(serves 4; prep time 40 min)

for the corn

3 tbsp unsalted butter

1/2 large white onion, finely chopped

2 medium garlic cloves, peeled and finely chopped

1/2 serrano chile, seeds removed, if desired, and finely chopped

1 1/4 tsp kosher salt, plus more as needed

2 fresh epazote leaves (whole) or 1 tsp dried oregano

5 cups fresh corn kernels (from about 10 cobs of corn, or use frozen corn kernels)

2 1/2 cups water

1/4 cup mayonnaise

for serving

crumbled Cotija cheese

crushed chile piquin or red pepper flakes

crushed Tamalitoz candies, tamarind flavour

fresh lime juice

1. Melt the butter in a large frying pan set over medium heat. Add the onion and garlic and cook, stirring occasionally, until soft and translucent, about 5 minutes.

2. Add the serrano chile, salt and epazote leaves (or oregano), followed by the corn kernels and the water. (The water should barely cover the mixture.) Raise the heat to high and bring to a boil, then lower the heat to medium and cook, stirring occasionally, until the corn is tender and the liquid has almost completely evaporated, 30-35 minutes. Taste and add more salt, if needed.

3. Remove from the heat and discard the epazote. Add the mayonnaise and stir to combine.

4. Divide the corn mixture into four tall cups. Top with the Cotija cheese, chile piquin and crushed tamarind candies, to taste. Drizzle each cup with a little lime juice just before serving.

TAHINI BROWNIES

(serves 6; prep time 15 min, baking time 22 min)

3 tbsp almond flour

1/4 cup cocoa powder

1/2 tsp kosher salt

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

1/2 cup well-stirred tahini

4 ounces baking chocolate, roughly chopped

2 large eggs

1/2 cup granulated sugar

1 tsp vanilla extract

1/2 cup chocolate chips

flaky sea salt, for sprinkling

1. Heat the oven to 350˚F and lightly grease an 8-by-8-inch dish. In a small bowl, whisk together the almond flour, cocoa powder and kosher salt and set aside.

2. Combine the oil, tahini and chopped baking chocolate in a small saucepan set over medium-low heat and cook, stirring often, until the chocolate is melted and the mixture is smooth. Remove from the heat and let cool slightly.

3. Meanwhile, in a large bowl, vigorously whisk together the eggs and sugar until frothy, 3-5 minutes. Whisk in the vanilla, followed by the cooled chocolate mixture.

4. Add the dry ingredients to the chocolate mixture and stir to combine, then fold in the chocolate chips.

5. Transfer the batter to the prepared pan, smoothing the top, then sprinkle lightly with flaky sea salt. Bake until a tester inserted in the centre comes out clean, 18-22 minutes. Remove from the oven and place the pan on a wire rack to cool. Serve warm or at room temperature.

APRICOT ALMOND CHAROSET TRUFFLES

(makes about 3 dozen; prep time 15 min plus chilling)

2 cups pitted and chopped medjool dates

1 cup chopped dried apricots

1 cup golden raisins

1 cup roasted salted almonds

1 tbsp honey

3 tbsp sweet red wine (or grape juice)

1. Working in batches, add the dates, apricots, raisins, almonds and honey to a food processor and pulse until a textured paste forms. Transfer the mixture to a bowl and stir in the wine, 1 tablespoon at a time.

2. Scoop out tablespoons of the mixture and, using lightly moistened hands, roll them into balls. Place the truffles on a baking sheet or large plate lined with parchment paper as you go.

3. Refrigerate the truffles (uncovered is fine) for 2 hours, then transfer to a container with a lid and continue to refrigerate until needed. Serve chilled or at room temperature.