Cabbage matzah never tasted so … good? (photo from pixabay.com)

Have you ever eaten cabbage matzah? Probably not. But, in Chelm, the village of fools, they still talk about it….

Many winters ago, to battle an outburst of influenza, the villagers of Chelm used all their chickens and most of their vegetables to feed their sick neighbours in Smyrna a healing chicken soup. The Smyrnans got better, but, in Chelm, all that was left was cabbage.

Because of this food shortage, the Chelmener ate cabbage for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Mrs. Chaipul in her restaurant served cabbage porridge, cabbage stew, cabbage stuffed with cabbage, cabbage brisket (don’t ask) and cabbage cake for dessert.

No one was happy. The children whined, teenagers complained, fathers groused and mothers growled and snapped. Only Doodle the orphan, who had an unfathomable love of cabbage, enjoyed the food. But, he quickly learned to keep his appreciation to himself.

Reb Cantor the merchant had hoped for a delivery, but supplies were not expected to arrive until after Passover.

One morning, there was a timid knock on the door to Rabbi Kibbitz’s study.

“Go away!” The learned man was cranky from excessive consumption of cabbage.

Rabbi Abrahms nudged Reb Stein the baker into the room. “We’ve come up with a solution.”

“Rye bread?” Rabbi Kibbitz’s eyes gleamed hungrily. “Challah? Babke? Strudel?”

“Stop it! No!” Reb Stein cried. “You’re making me hungry. I have invented cabbage matzah.”

The wise rabbi stared at his friend the baker. “That sounds horrible.”

“It is,” Reb Stein admitted.

“But it’s kosher for Passover!” explained Rabbi Abrahms, the mashgiach responsible for everything kosher.

“No one is going to want it.” The poor baker was near tears.

“Bake it anyway,” sighed Rabbi Kibbitz. “I’ll pay for it out of the discretionary fund.”

Reb Stein nodded glumly and returned to his bakery.

The weather was fine that year, so the villagers planned the community seder to be outdoors in the round village square.

“The menu is a marvel,” Mrs. Chaipul sarcastically explained to Rabbi Kibbitz. “Cabbage ball soup, chopped cabbage liver, poached cabbage, braised cabbage, cabbage charoses and, of course, Reb Stein’s cabbage matzah for the afikomen.”

Rabbi Kibbitz suppressed a wave of nausea. “At least we’ll be outside, so we won’t smell it.”

Aside from young Doodle, no one was looking forward to Passover.

On erev Pesach, everyone trudged to the round village square to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt. With a sigh and a blessing, the service began.

The wine flowed. Reb Cantor the merchant had opened a locked cellar and rolled five barrels of “I don’t know what vintage it is, but it’s not cabbage” to the round square.

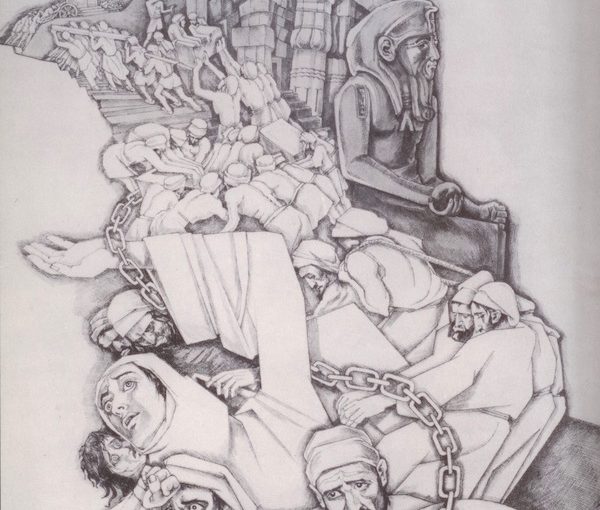

“This is truly the bread of affliction,” Rabbi Kibbitz said as the thick brassica afikomen snapped with a resonating crack!

Reb Stein looked doleful.

At last, after the Hamotzi, everyone tasted the so-called matzah.

It was revolting. Not only was the greenish cabbage matzah bitter and sour and cabbage-flavoured, it was dry and stuck to the roof of your mouth and your teeth like grout on tile.

Everyone quickly mumbled another blessing, and gulped down another cup of wine.

Through his tears, Reb Stein the baker, who was a craftsman at heart, began to laugh. His laughter spread around the table. It grew loud. It grew raucous.

Young Doodle took the opportunity to jump up onto a table and bang his glass with a spoon.

Quickly the laughter died down. Such behaviour in the middle of a seder had never been seen! Fortunately, Doodle had taken off his shoes and wore clean socks because Mrs. Kimmelman never would have forgiven him for getting dirty footprints on her best tablecloth.

Doodle began, “I know that you all hate cabbage!”

There were cheers and boos and applause.

“But,” he continued, “I look around and see my whole community gathered together and I can’t help but think how grateful I am. We have our health. We have our homes. We have one another to support us.”

It is rare for the villagers of Chelm (or indeed any gathering of Jews at mealtime) to fall quiet, but a hush spread.

“We are blessed that we live in peace and freedom, and are not enslaved.”

Now there was nodding and shouts of, “Amen!”

“Raise a glass with me,” Doodle said.

All glasses were held high.

“For this cabbage that we eat tonight,” Doodle said, “represents the hope that, one day, all women, all men, all people will be freed from oppression and slavery.”

“And freed from more cabbage!” heckled Adam and Abraham Schlemiel together.

“May we all live in peace!” shouted Rabbi Kibbitz, who had gotten completely caught up in the moment.

Then, with a rousing “Mazel tov!” the villagers of Chelm toasted, drank and ate with gusto.

The next morning, Rabbi Kibbitz realized something as he talked with Mrs. Chaipul.

“Actually, that was one of the best seders ever. And the food.…” The wise old man looked around the restaurant to make sure no one else was listening. “The food was delicious.”

The wise old woman smiled, thought about it, nodded and asked, “So, shall I order some cabbage matzah for next year?”

“No,” laughed the rabbi. “Never again!”

Mark Binder is the author of The Misadventures of Rabbi Kibbitz and Mrs. Chaipul, Matzah Misugas, and many other “Life in Chelm” stories. Visit his website at markbinderbooks.com.

* * *

Reb Stein’s Kroyt Matzah

- Grind one large dried cabbage very fine.

- Stir in just enough water, so it forms a gruel-like slurry.

- No salt. No yeast!

- Spread it thickly with a trowel on a baking sheet.

- Bake in a really hot oven until crisp but not black.

- Serve with cabbage butter, chopped cabbage livers (don’t ask) and cabbage jam.

- Enjoy with friends and family.