Jocelyn Barrable-Segal (photo by Olga Livshin)

Jocelyn Barrable-Segal was raised by parents with two vastly different professional backgrounds: her mother was an architect and her father was a pilot. Following her own path, Barrable-Segal managed to combine the two in her own career. For 35 years, she has been a flight attendant with Air Canada. Several days each month, she flies around the world. The days she is not in the air, she is an artist, and you can find her at Malaspina Printmakers, a printmakers’ workshop on Granville Island, where she creates unique lithographs.

“Malaspina is an artist-run centre,” Barrable-Segal told the Jewish Independent on a recent visit. “It started in the early ’70s with three or four artists. Now there are about 60 of us.” She went on to explain that Malaspina is equipped for a dozen different systems used in printmaking, but she uses only one process, the ancient technique of stone lithography. “I love to draw,” she said, “and lithography is the only technique that requires drawing.”

Barrable-Segal does that drawing on stone. The technicalities of embedding an image into stone and later transferring it from stone to paper are not for this short article, but it’s important to point out that each image can have many layers, each layer introducing one additional color plus whatever details the artist wants to add or alter. The process is time consuming and labor intensive, but Barrable-Segal said she doesn’t conceive of working in any other art form.

“With lithographs, you can change the image if you change your mind, have layers of drawing and colors,” she said, “while in painting, as soon as you’re done, that’s it.” She also likes to be able to have several copies of the same print, although she never mass-produces them. “I make limited editions, no more than seven copies of one print.”

Her prints are mostly flowers or landscapes but they are never life-like. They hover between abstract and impressionism. “I’m attracted to metaphors,” she said. She uses multiple sources for her pictures, including photographs from her travels, but she transforms the imagery through the creative filter of her imagination, enriches reality with emotional and esthetic folds. Her artistic touch converts memory into art.

That’s why she keeps flying, to bring back more visual mementos, more nutrients for her lithographs, she explained. “I see different countries, and each happy place finds its way into my images. Of course, no photocopies.”

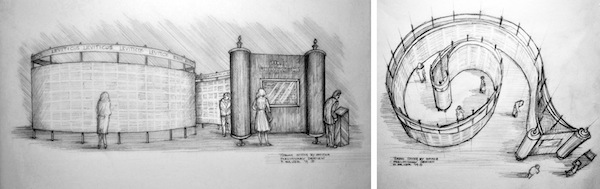

Frequently, she draws flowers and floral compositions. “I buy live flowers at the public market and look at them,” she said. “That’s how it starts.” Flowers are the predominant theme for her work in the In Wait show that recently opened at Burnaby Art Gallery.

“In Wait is a collaborative project of the Full Circle Art Collective,” she said. “There are seven of us in the collective, seven women: Heather Aston, Hannamari Jalovaara, Julie McIntyre, Milos Jones, Wendy Morosoff Smith, Rina Pita and me. We all met at Malaspina, but then some of us drifted apart. We reunited for this show.”

The inspiration for the show came from the story of Penelope, the wife of Odysseus, she said, and it took the artists three years from the idea to the vernissage.

“Penelope was waiting for her husband to return, but her suitors were insistent that he was dead and she should choose one of them. She said she would weave a shroud before she married again. All day long she wove and then, in the night, her ladies-in-wait would unweave what she had done. The shroud was never completed. She waited. We all wait for something in our lives. It’s a universal theme for women.”

For her, another sad theme overlaid the waiting – the theme of grief. Her parents passed away recently, and working on the show helped her deal with her sadness. “For me, grief associated with poppies. I needed to find solace. I drew lots of poppies for the show.”

Women friends and their collaboration and support were another aspect of the show that came from the story of Penelope and her faithful maids. “Each one of us would make a piece and pass it on to the others. The others would add something, change. They would say: what does it need? Perhaps this detail or line or color should be added.”

Sometimes three or four people would contribute to the image before it returned to the original artist. “When you get your image back with someone else’s input, you think: what do I do now? It’s different. How to keep the integrity of the image? How to bring our combined visions together? This way, you’re always creating.”

Art making is ingrained in Barrable-Segal’s life. “I started flying because I didn’t want to be a full-time artist. It’s not realistic, even though I have a master’s degree in fine arts. But I would never abandon art. I do it for myself. I would continue even if I didn’t sell anything. I always have my sketchbook with me. When I play golf with my husband, I’m not interested in the ball. I look at my shadow on the grass and think how it would look in a lithograph.”

In Wait is at Burnaby Art Gallery until Nov. 9. For more on Barrable-Segal, visit jmbs.ca.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected].