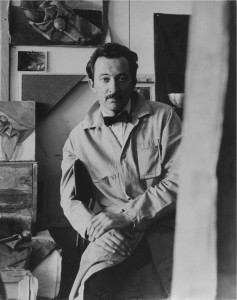

Shevy Levy’s Storm Brewing is at Zack Gallery until Dec. 6. (photo by Olga Livshin)

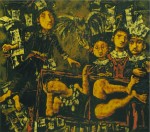

This month, Zack Gallery is dedicated to abstract art. The exhibition Storm Brewing introduces gallery patrons to an unusual artist, Shevy Levy. Nobody looking at her daring, color-splashed paintings, throbbing with élan, could guess that Levy is an amateur artist. In her professional life, she is the owner of a software company, Lambda Solutions.

“I don’t have a formal art education,” Levy said in an interview with the Independent. “I always liked art and design, painted at school, and my mother encouraged my interest in art. She urged me to take classes, to study, but I was drawn to science, too. When the time came to choose between art and science as a career, I chose science and got a math degree. Much more practical,” she laughed. “But art was always in my life. You could say it is in my blood. I heard that math and creativity originate in the same part of the brain.”

Levy has taken classes with many famous artists, first in Israel, where she was born, and then here, in Vancouver, after her family immigrated. “I’m still learning, still enrolling in art courses. It’s a lifelong study,” she said, “an ongoing journey to learn new techniques and skills, develop them. The better your skills, the wider their range, the more they allow you to express yourself.”

Levy’s visual language consists mostly of colorful abstract compositions. Colors flow and clash, tinkle and thrum like an orchestra, twirl like dance strains and float like snowflakes. “I like nature and colors, not so much shapes,” she explained. “When I paint, I don’t plan. I just want to express myself. What color would fit here? What color should be there? It’s all intuitive. I want tons of energy on my canvases and I pour it out through colors.”

Light and darkness interlink in her paintings as they do in our lives, and in her own life, which hasn’t been easy or straightforward. “We came to Canada in 1993,” she recalled. “My husband retired from the Israeli air force and I took a sabbatical from teaching math. Our children were 10 and 15 at the time. We decided to travel for a year and came here. I did my master’s degree at SFU [Simon Fraser University]. We stayed.”

Of course, it wasn’t that simple. The life of an immigrant is never simple. It requires much time and energy to build a new home in a new country, to integrate into a new culture. There was no time for art.

“I painted a lot while in Israel, but when we came here, I stopped for awhile,” she said. “I started painting again about 10 years ago, and now I don’t see myself stopping. I’m busy with my work, I love it, but I love painting, too. I paint in the evenings and on the weekends. It’s my way to meditate, to relax, a distraction from real life.”

Levy also started taking classes again, and every new class offered a new discovery. “I always thought I had an intuition for colors, how they fit together. Then I took a class on colors at Emily Carr, and it explained so much. It was very helpful to know what the colors mean, alone or in different combinations. It is like there is a conversation of colors in my paintings.”

The sense of communication, of wordless discussion through the paintings comes from the artist’s original approach. “I always paint several pieces at the same time. I can’t do just one. I need continuity, from one painting to another. Sometimes I paint on top of older paintings. It might be beautiful, esthetic, but if there is no ‘umph,’ I have to fix it. I need to see a story in each painting, a conflict, a tension, where color clusters interact with empty space.”

For the current show, the story is all about storms – both in art and in life. “The idea for this show was not only to investigate the storms in nature but also to reflect on what storms make us feel,” said Levy. “We are facing storms all the time in our lives. There are darker clouds and lighter moments. But storms are not necessarily black. I wanted to know how a storm would look in pink. Could it be white? It was an exploration of the theme, and every painting has a title that came from music, from songs. I couldn’t live my life without music. I always put on music when I paint. I love classical music, jazz, rock.”

Like notes that build into melodies, the paintings of the exhibit create a concert of colors on the gallery walls. Some pieces are like symphonies, deep and powerful, while others look like doodles coming alive, buzzing with current and bursting with the artist’s emotions.

Levy seems to be drawn towards the darker spectrum of the palette, where happiness is tempered with concern. “Sometimes I force myself into a ‘cheerful mood’ but generally I think life is darker,” she said. “My sister is going through a serious illness now. Maybe the darkness in my paintings comes from it.”

Storm Brewing opened on Nov. 12 and will continue until Dec. 6.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected].