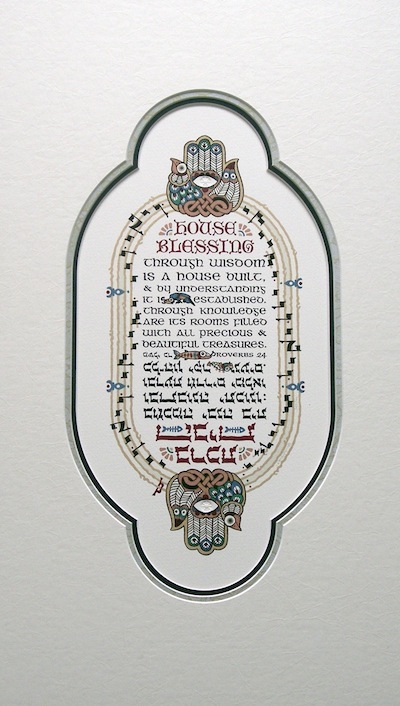

The Vancouver skyline, photographed and painted by Sharon Tenenbaum.

Sharon Tenenbaum is celebrating her 10-year anniversary – since becoming an artist photographer – with a solo exhibition at Zack Gallery. The exhibit includes photographs from a number of different series, an eclectic selection reflecting the progressive stages of her artistic journey.

“It’s the hardest challenge for any artist to constantly reinvent herself, both business-wise and creative-wise,” Tenenbaum said in an interview with the Independent. “Everything has a shelf life, so we have to come up with something new every few years.”

In the decade since she began, Tenenbaum has reinvented herself several times, although she never abandons her previous endeavors. Her first love was architectural photography, and it is still an important part of her artistic output.

“Maybe because I was an engineer before I became an artist, I like architectural photography,” she said. “You can take your time with buildings and bridges, come to them again and again, see them from many angles and in different weather. With people, it is transitory: a moment, and it is gone.”

Tenenbaum’s architectural photography has won awards. The most recent one came last year, when her Musical Reflections Hoofddorp Bridge Series won first place in the 2015 International Photography Award, in the category of architecture, bridges. All three photographs in the series are on display at the Zack.

“These three bridges, with musical names Harp, Lute and Lyre, are located in the small town of Hoofddorp, Holland, on the outskirts of Amsterdam,” Tenenbaum explained. “They were designed by the Spanish engineer and architect Santiago Calatrava. I love his works and I photographed them before.”

Although her architectural photography started as black and white, a few years later, she began painting the photographs. Her painting phase started with trees.

“I started with one image of a tree, a photo from Portugal,” she said. “Then, there was a maple tree outside my window; it was gorgeous in the fall. I wanted to convey its beauty with my image, too.”

These works are the result of a two-step process. First, Tenenbaum prints her photos on canvas and then she paints the canvas with acrylics. People coming to Zack Gallery will see several of these painted photos in the show.

After her tree paintings proved successful, Tenenbaum moved to paint a different kind of photographic imagery – the Vancouver skyline.

“I was inspired to do this after I saw a painter in Jerusalem about two years ago, Adriana Naveh. Her abstract urban landscapes were amazing. I was blown away by her work,” said Tenenbaum. “But not every architectural image submits well to painting. Sometimes, I try to paint something but it doesn’t work out. It’s hard to explain what works and what doesn’t. I think if the image is too architecturally clean, it needs the black-and-white palette.”

The examples of Tenenbaum’s painted skylines in the Zack show combine the technical proficiency of the photographer with deep emotional undertones echoing through the color schemes. The skyline might be of the same place – Vancouver – but each image is different, reflecting different facets of the artist’s inner self.

The Vancouver skyline fascinates Tenenbaum. Recently, she started a new project showcasing her favorite subject. She creates photo images of the skyline assembled exclusively from spare bicycle parts. She calls this new project Bike Art.

“I love biking and I always look for new and original ways to depict Vancouver. This project is a melding of my two passions,” she explained. “I use the recycled bicycle parts from the bike shops, the parts the shops would throw away. It’s a very time-consuming process, lots of work, and my place resembles a bike garage now, but it is very rewarding. I only have three images for now and I would like to get a grant to continue this project.”

Tenenbaum’s unique skylines made with bicycle parts are charming, quaint and amazingly authentic. One can see the ocean and Stanley Park, the skyscrapers of downtown and the masts of the marina, all created with recycled screws and bolts. “The viewers could interpret the images anyway they like,” she said.

But certain images are harder to fathom, like the image of an airplane flying above the clouds. The photo is just across from the entrance to the gallery, greeting guests with its mystery. “Many people ask me how I did it,” said Tenenbaum. “I always tell them: take my class and find out.”

Tenenbaum is eager to share her extensive expertise. She teaches students to use a number of photographic techniques to create fine art, to express their souls, and not just document what they see. With two different classes at Langara College plus some private tutorships, her teaching schedule is extremely busy, but she finds time for international workshops as well. “I have one in Chicago next year,” she said.

The show Sharon Tenenbaum – Architectural Fine Art Photography opened on Dec. 15 and continues to Jan. 15. For more information on Tenenbaum and her work, visit sharontenenbaum.com.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected].