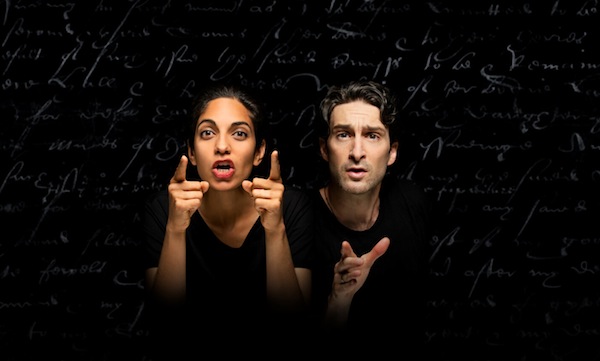

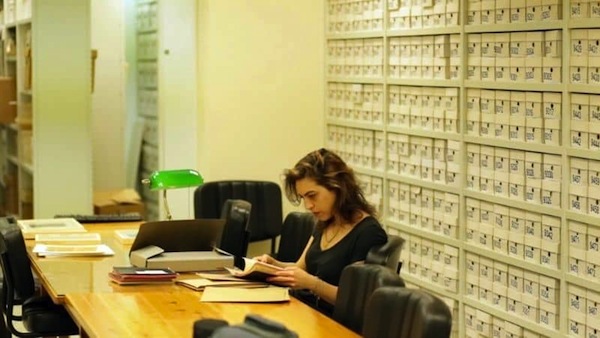

Maxine Lee Ewaschuk, in a still from the documentary Periphery, which premièred last month at the Prosserman Jewish Community Centre in North York, and is available to view online.

On Oct. 28, the Prosserman Jewish Community Centre in North York hosted a hybrid launch for Periphery, a newly produced documentary film and photo exhibit that explores the lives of multiracial and multiethnic Jews within the Greater Toronto Area.

The 27-minute film features interviews with several individuals who might be considered as existing on the fringes of a homogenous, stereotypical notion of the Jewish world – a world that, in reality, is multifaceted and ever-evolving.

“What Periphery does for us is bring together a diverse view of our community,” said Andrew Levy, one of the event’s organizers.

From the outset, the film asks, “What makes a Jew? What do you have to know to be a Jew?” Implicit in those questions is another question, how can the Jewish community extend its tent to include those who might feel left out of the broader mishpachah, family? Notably, those whose parents are not both Jewish.

“There becomes a question of, can I say I am Jewish? When can I say I am Jewish? Is it ever OK for me to say I am Jewish before I complete my conversion, even if I am functioning very Jewishly in my day-to-day life. Sometimes, I say I am a Jew-in-progress,” shared dancer Maxine Lee Ewaschuk.

“Maybe I don’t know everything about what it is to be Jewish, but I am fiercely, proudly Jewish. It’s my experience and my experience is valid,” said actor Nobu Adilman, whose heritage is Jewish and Japanese.

“I knew my Indian grandparents super well, but I never knew where my Jewish grandparents came from,” said author Devyani Saltzman, who recounted a trip to Russia with her father to look into the roots of the paternal side of her family.

Saltzman also remembered an observation she had as a child of looking at other classmates who came from solely Hindu or Jewish families and thinking, non-judgmentally, “that must be really nice to know one’s place and space so clearly.”

In the cases of both Adilman and Saltzman, their parents married out of a love that transcended religious, cultural and geographic barriers.

“My father put a lot of his energy into my mother’s culture. He didn’t talk a lot about his upbringing. He was proudly Jewish, but he didn’t want to impose it on us,” Adilman said.

Adilman, too, related a kinship he has with other Jewish people who have gone through the same sorts of questioning that he has.

Ariella Daniels, Daniel Sourani and Sarah Aklilu each spoke of connections to places far removed from the GTA.

Daniels, who descends from Bene Israel Jews of India, explained that, for her, being a Jew represents several layers of identity – cultural, religious and national – and that the perspective she has of the world comes through being Jewish.

Sourani, who identifies as a gay, Iraqi Jew, focused on the importance of family – and the gatherings around Shabbat, holidays and lifecycle events – to his Jewish experience.

Aklilu, meanwhile, sees herself as Jewish, Ethiopian and Canadian. She told of the many times her Jewish identity has been called into question and, as a result, she has questioned who she is. Ultimately, she asserted, “I know I am Jewish and I feel that I don’t need to explain to people that I am.”

Tema Smith, a Jewish community professional and daughter of a Black father and Jewish mother, outlined the odd experiences she has had because people often assume she has two European Jewish parents.

“People say things that they would never say if a Black person were in the room. I feel completely unseen in those moments,” Smith said. “I feel trapped in these weird moments of having to swallow what just happened.”

For Asha, a Black and Jewish woman, her connection to Judaism is one that she described as developing and expanding. “I think, if you look Black, like I do, then you go through life as a Black person,” she said. “I don’t know if you have to choose internally, but it is chosen for you in the wider world. So, people don’t look at me and think I am Jewish. I don’t think that’s ever going to happen. If it did, it would be weird.”

While the experiences in Jewish spaces of those interviewed were frequently frustrating and alienating, it was also pointed out in the documentary that there are positive aspects to having a multiracial background. There is richness and happiness in belonging to different cultures and this, in itself, can be invigorating.

The screening was followed by a conversation with director Sara Yacobi-Harris, cinematographer Marcus Armstrong and film participants. Periphery was produced by No Silence on Race, an organization that seeks to establish racial equity and inclusivity within Jewish spaces in Canada, in partnership with the Ontario Jewish Archives. To view the film, visit virtualjcc.com/watch/periphery.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.