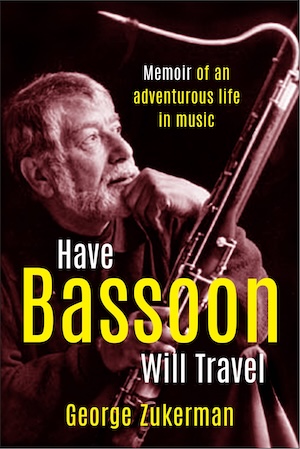

Imre Székely, left, gives his artwork to then-prime minister Jean Chrétien. (photo from szekelygallery.com)

From his hometown of Győr, Hungary, a city halfway between Vienna and Budapest along the Danube River, to his studio in Victoria’s Chinatown, Jewish community member Imre Székely has been creating art for more than five decades, primarily in the linocut/monotype style of printmaking.

Linocut, also known as lino print, is a design carved in relief in linoleum. The art form was popularized in the early part of the 20th century. In monotype, an artist presses ink directly onto a plate. The plate is then pressed against paper to transfer the ink.

Székely discovered his calling early in life, under the tutelage of Imre Krausz and István Tóvári-Tóth, both distinguished artists in Hungary. However, Hungary in the 1970s and 1980s was no place for anyone whose views differed from those of the regime.

“The communist regime at the time did not have a role for a forward-thinking, modern artist. There wasn’t much chance of self-actualization,” Székely told the Independent.

Thus, in 1987, he said goodbye to his family and jumped on a westward-bound bus. His first stop was a refugee camp in Austria, then on to France, the Netherlands and, finally, Canada, in 1988. After stops in Winnipeg and Toronto, he set off west where, in 1991, he settled in Victoria, finding the provincial capital to be an ideal spot for his professional and private life. His wife and children joined him shortly after he arrived in British Columbia.

Székely describes himself as a hyper-surrealist artist, who blends “a variety of colours, patterns and shapes that are the spices of life.”

Throughout his career, he has donated his works and given them to people who couldn’t otherwise afford a work of art. He also has presented his artwork to provincial ministers, foreign dignitaries and prime ministers.

In 1999, for example, he traveled to Rome for a personal audience with Pope John Paul II, to donate his work “Abba Pater” to the Vatican.

In 2001, he showed his gratitude to his adopted homeland by donating his art-deco-styled piece “Canada: Past, Present and Future,” to then-prime minister Jean Chrétien, who accepted it on behalf of the government of Canada.

“This occasion was especially meaningful to me, as it presented a way to express my thanks to Canada for accepting so many refugees to this country with open arms,” said Székely, who has also presented a work to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

“Gifting Justin Trudeau with one of my art pieces was a highlight in my life … this kind of event was impossible in my home country under communist rule,” he told Senior Living Magazine in 2021.

One of the works of which he is most proud, “Hungarian Conquest (Honfoglalás),” was presented to the Hungarian parliament in Budapest. When, in 2010, Pecs, Hungary, was chosen as the European Capital of Culture, Székely provided the city with 31 of his works for a solo exhibition. His hometown Győr’s city hall houses his artwork and he has donated his works locally, to the City of Victoria and to the Hungarian consulate in Vancouver.

At the height of the COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020, retreating to his studio, Székely produced “Satan Sneers,” a work in which, as an artist, he detaches himself from shared circumstances to show pity for the human race as it confronts an undetermined fate.

Székely sent a photo of the work to Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesu, director-general of the World Health Organization, in the hope of donating the work. According to Székely, Dr. Tedros (his preferred moniker) liked the piece very much.

“Unfortunately, I couldn’t personally hand it over to him in Geneva at the time because the two-week quarantine was introduced before my departure,” Székely recalled.

In 2021, the artist created a work entitled “Hope and Genius,” dedicated to Katalin Karikó, the biochemist and researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, who, together with Drew Weissman, took home the 2023 Nobel Prize in medicine for work leading to the discovery of mRNA vaccines to fight COVID-19.

“She deserves lots of thanks and appreciation from us all,” he said. “My work is recognition and homage to her human and scientific greatness.”

At present, Székely is working on several projects, one of which is called “Magical Artificial Intelligence,” a surrealistic piece on what he views as the issue that offers the most positive potential for humanity – and the most danger.

He hopes to donate works to other notable people in the political and business worlds, such as Bill Gates, Kamala Harris and Ernő Rubik, a fellow Hungarian who invented the Rubik’s Cube.

As he approaches his 70th birthday in December, Székely said he feels freer now than at any time in the past, drawing strength from family, friends and art.

“Artistic creation is the outflow of strength, good mood and joy of life. A true artist enjoys his own creative power. Creation is one of the most difficult things in the world, creating from nothing,” he said.

“I am convinced that art and culture will unite the world again. I know that artistic ability can be viewed as a blessing, but it is worthless without creative work and humility.”

For more on Székely, visit szekelygallery.com.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.