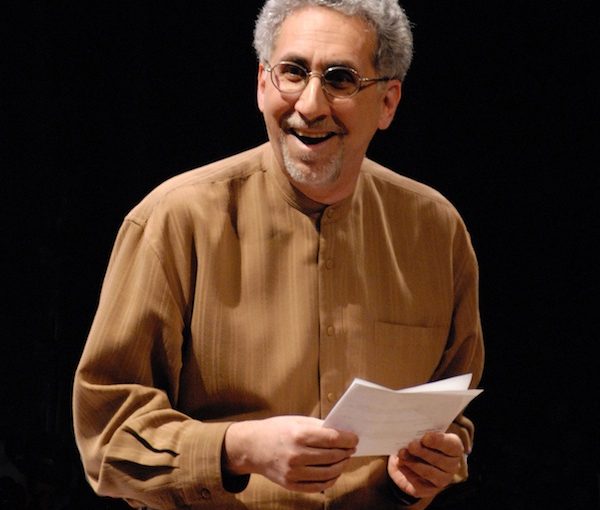

Ayelet Rose Gottlieb released two new collaborative CDs this year. (photo by Sergio Veranes)

Ayelet Rose Gottlieb released two new collaborative CDs this year: Who Has Seen the Wind? by the group Pneuma and I Carry Your Heart: A Tribute to Arnie Lawrence. Both creative endeavours will appeal to those who appreciate top-level musicianship, improvisation and meaning beyond the notes.

As she has done with other recordings, Who Has Seen the Wind?, which was released on Songlines, centres around a theme. In this case, the wind. Gottlieb and James Falzone, François Houle and Michael Winograd – clarinetists and fellow composers – have written music inspired by a range of poetry from various cultures, including Iranian and Japanese. The title of the CD comes from a poem by English poet Christina Rossetti of the same name, and Pneuma means breath, spirit or soul in ancient Greek.

I Carry Your Heart: A Tribute to Arnie Lawrence, which was released on Ride Symbol Records, also has poetry as one of its foundations, but it is, as its name says, a tribute to Arnie Lawrence and, specifically, his record Inside An Hourglass.

“Arnie’s Inside an Hourglass album has always been one of my favourite Arnie Lawrence records,” Gottlieb told the Independent. “In 1969, he went into the studio with his band and with his 8-year-old son Erik and with 5-year-old Dickie Davis Jr. (son of bassist Richard Davis). The band and children played a full record worth of improvised music together. This improvisation was released on the record label owned by the great flautist Herbie Mann.

“When I became a mother, this record started resonating with me in a new way. It reflected something of how I wanted to be a parent – in freedom, in music, in improvisation, with my kids and not in an ‘alternate reality’ that is separate from them.

“At one point,” she said, “I spoke to Arnie’s son, Erik, about the idea of revisiting the concept of that original album. Erik jumped on board and, along with my three little kids and our mutual friend and musical partner, Anat Fort, we went into pianist Chris Gestrin’s home studio in Coquitlam, B.C. My three little kids were 2 years old (twins) and 7 months old at the time of the recording. Baby Maia was with us for the full eight hours and the twins were there for about four hours. We also used some pre-recorded sounds that I edited in advance to create daily-sound tapestries for us to improvise over.

“We brought in some poetry by Arnie and E. E. Cummings and we let the day unfold as it did. The music on this album is all fully improvised – unrehearsed and unplanned. The biggest challenge was then to choose what to toss and what to keep. We loved so much of what came of this once-in-a-lifetime session.

“Our album is not a remake, but rather a revisiting of Arnie’s 1969 concept,” she stressed. “It’s a tribute to him and an extension of what he started back then, when his son was 8 years old. Fifty years later, Erik was creating this homage to his first album, now as the adult in the room, with his father’s mentee and her three children.”

Gottlieb met the elder Lawrence in Israel, where she grew up, when she was 16 years old; he had moved to Jerusalem from New York.

“He was the first to throw me into the deep waters of jazz,” she said. “My dear friend, fellow vocalist Julia Feldman, and I would go hear him play at the restaurant above the Khan Theatre. One day, someone told Arnie that the two teenagers sitting in the corner night after night are singers! At the start of the next set, somewhere around the middle of the first tune, Arnie walked up to me with a mic and commanded – ‘Sing.’ And that, I did.

“From that night on, Julia and I would frequent any restaurant, café or club he played at. In order to be able to hang with the ever-changing, always burning band, I memorized hundreds of tunes off of my father’s LPs and transcribed countless solos. After awhile, Arnie started calling me to perform with him, not as a sit-in guest, but as an equal on the bandstand. I always felt that playing alongside Arnie elevated my own playing to new levels. His trust in me allowed me to trust myself and my own musicality, at the fragile age of 17.”

Around this time, Gottlieb began composing. “I was finding my voice and my place in music,” she said. “When, at 19, I decided to go study at New England Conservatory in Boston, Arnie, who was my greatest advocate, wrote a wonderful recommendation letter, which felt like he was delivering me to my future teachers – Ran Blake, Dominique Eade, George Russell and others.

“Though my time with Arnie was spent primarily playing jazz standards, I feel that he gave me my foundations as a composer, improviser and as an educator. He taught me to work deeply with my ears, and to be present and connected. He gave me his trust, before I really did anything to deserve it. And this trust gave me the wings I still use to fly.”

Gottlieb is an avid poetry reader and collector, and has “shelves full of books and folders full of files with texts that I may or may not use some day, but they ‘feed’ me with inspiration and insight, daily. In recent years,” she said, “I’ve also been working as a poetry and prose translator from Hebrew to English.”

She sees everything, “through ‘glasses’ of music and poetry,” she said. “Music informs all of my experiences and poetry is built into my world of associations and my way of expressing myself in the world. When I compose, perform or improvise, I am the most ‘me,’ without filters. It feels like a calling, and a personal necessity. I’ve never had a time in my life in which I didn’t have music. It has been my companion and an extension of me, ever since I can remember myself. Some of my earliest memories involve music-making.

“It is also my portal into the world of spirit,” she said. “I experience inspiration in a great variety of ways. I often feel that the music I’m writing or improvising is received, rather than created. Of course, there is lots of knowledge, experience and work that goes into it, too. But this instinctual, primal connection is at the core of all of my works. This is why, when I make music, I do not think about anything other than what the music asks of me.

“I start thinking about the audience when it’s time to birth the music into a physical existence – when I’m working on packaging, releasing an album, bookings, getting the word out about it, etc.”

As an example of this transition from inner to outer focus, Gottlieb gave Pneuma, all of the members of which contributed to Who Has Seen the Wind?

“My contribution,” she said, “was a six-part song cycle based on Christina Rossetti’s poem ‘Who Has Seen the Wind?’…. This song cycle is a great example of my connection to music and poetry.

“The idea to work with clarinets was inspired by my paternal grandfather, who was an amateur clarinetist. Right from the start, this project was a way for me to communicate with him, and continue our connection and relationship beyond the limitations of the physical world. How wonderful to have such a thing as music, which bridges the gap between the earthly and the spheres beyond it!

“Christina Rossetti’s poem, which I know so well, kept surfacing in my associations as I was walking the streets of Vancouver with my babies in the stroller, in autumn 2016. From this poem, eventually emerged the form of this composition.”

When it came time to bring the music into physical form, the band members and their producer, Tony Reif, chose photographs for the CD sleeve by B.C.-based photographer Gem Salsberg, which, said Gottlieb, “pair a visual with the music, making it all the more accessible and clarifying our intensions with this set of music, inspired by the wind. We wrote liner notes, to bring our audience even further into the process of the creation and the stories behind the tunes. The album was released with a beautiful 16-page booklet, with all of the poetry printed.”

While the CD was released just this year, Pneuma’s première performance was at the Vancouver Jazz Festival in 2017.

“I love interacting with audiences,” said Gottlieb, “hearing people’s experiences with the music I make, answering questions, sharing muses, etc. The audience and their support fills my batteries as I continue on my path in music. There is always that back and forth between the internal work that is required in order to create the work and the external, open part of it – which is about sharing it generously, with as many people as possible.”

For more information on or to purchase either of these CDs, or other Gottlieb albums, visit ayeletrose.com.