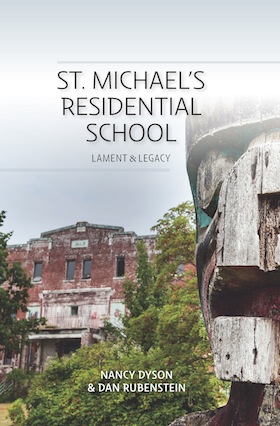

St. Michael’s Residential School in 2013, Alert Bay, B.C. (Courtesy Hans Tammemagi, from the book St. Michael’s Residential School: Lament & Legacy)

In 1970, Nancy Dyson and her husband, Dan Rubenstein, worked for a short time at the Alert Bay Student Residence, previously and most commonly known as St. Michael’s Indian Residential School. Dyson shares their experiences, with a brief section by Rubenstein, in the book St. Michael’s Residential School: Lament & Legacy (Ronsdale Press, 2021).

“This book is a must-read for all Canadians,” writes Chief Dr. Robert Joseph, ambassador for Reconciliation Canada and a survivor of St. Michael’s, in the foreword. “It is honest, fair and compelling. It is a story that screams out for human decency, justice and equality. It also calls for reconciliation and a new way forward! Two recently wed idealists arrive at Alert Bay on Canada’s Pacific central coast to work at St. Michael’s Residential School. They hire on as childcare workers. Little do Dan and Nancy in their youthful enthusiasm know they will be shaken to the core before too long.”

Yet, despite being shaken, the couple did not realize the extent of the abuse and harm being inflicted on their charges, nor that such abuse was being carried out across the country – and had been since the first schools opened in the 1800s to when the last one closed in 1996.

“In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Reports were released. Like many Canadians, we were shocked by the findings,” writes Dyson in the introduction. “Over a hundred-year span, thousands of Indigenous children had experienced what we had witnessed at St. Michael’s. Especially shocking were the stories of sexual abuse that had occurred along with the emotional and physical abuse we had witnessed. When we read the survivors’ statements and realized the lasting, tragic legacy of the schools, we felt compelled to share our story.”

The couple does so with the intent to bear witness to the survivors’ experience. “In adding our voices to the voices of survivors,” writes Dyson, “we hope that the history of residential schools will not be forgotten or denied.”

Dyson and Rubenstein were married in March 1970 in Rubenstein’s family home, near the campus of Vassar College, in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., from which Dyson graduated in May that year. A brief series of events landed them in Vancouver, where they decided to stay awhile, because Canada “seemed more benign and compassionate than the United States, which was then severely polarized by the Vietnam War.”

While staying with friends, they learned about openings for childcare workers at the residential school in Alert Bay. Along with one of those friends, they applied for the jobs and succeeded in getting interviews. The school administrator explained to them that St. Michael’s, which had been run by the Anglican Church, was taken over by the federal government in 1969 – this was a national change in policy, because of a Labour Relations Board of Canada ruling a few years earlier that school staff had to be paid as much as government employees doing similar jobs. The churches couldn’t afford the increased costs, so the government took over. Though, as Dyson notes – in dialogue given to the administrator – the churches still had “a strong influence.”

At the time that Dyson and Rubenstein joined St. Michael’s staff, the school wasn’t a school anymore, but a residence, with most of the kids attending public school in Alert Bay and the handful that made it to Grade 9 taking the ferry to Port McNeill for their education. Including Dyson and Rubenstein, there were seven childcare workers for 100-plus kids. Dyson was put in charge of 18 teenage girls and Rubenstein the 25 youngest boys, most of whom were 6 or 7 years old.

From the beginning, even before their interview, as they walk up the concrete steps of the residence, and notice the rusty radiators and drab hallways, they have misgivings. Their friend declined the job offer, but they accepted, thinking “it has to be better than living in the States.”

During their brief tenure at St. Michael’s, they witnessed the brutal treatment of the children, in the name of discipline, as well as the poor food, clothing, shelter and, of course, the kids weren’t allowed to learn anything about their own culture. There were suicides, some girls prostituted themselves, some students took their anger out on their peers.

Dyson and Rubenstein tried to support the kids and did indeed connect with a few of them. The couple tried to force some changes, along with other people in Alert Bay, but there was really no way they could improve the situation. Ultimately, Dyson couldn’t take it anymore and quit. Rubenstein, however, still wanted to try and change things from within, despite having been attacked with a knife by a cook who thought that the Jew among the Anglicans was the Antichrist. Rubenstein was fired from his job after he and Dyson shared their concerns about the residence with government inspectors.

The names of people in the book have been changed and the dialogue is based on memory. Dyson inserts excerpts from the TRC reports into her narrative to reinforce not only what she is saying about St. Michael’s but to show that what was happening there was, sadly and disgustingly, happening at residential schools across Canada.

The names of people in the book have been changed and the dialogue is based on memory. Dyson inserts excerpts from the TRC reports into her narrative to reinforce not only what she is saying about St. Michael’s but to show that what was happening there was, sadly and disgustingly, happening at residential schools across Canada.

Rubenstein’s story comes as an epilogue, after a section with some of his photos from 1970/71, as well as a few more recent ones, including of the reconciliation ceremony in Ottawa in 2015. Rubenstein writes about the continuing impact of the residential schools and some of his realizations. He speaks candidly of the difficulties he has in reconciling what he witnessed with the image he has of Canada “as a just and compassionate country.” As well, he admits, “I also struggle to reconcile my own sense of decency with my failure to advocate on behalf of the children after I left St. Michael’s. Like other Canadians – former childcare workers, teachers, administrators, principals, clergy and government officials – I remained silent.”

Dyson and Rubenstein have written St. Michael’s Residential School: Lament & Legacy not only to state publicly what they witnessed and did or didn’t do. They want to encourage other Canadians to join in the process of reconciliation, and offer some ideas for entry points, mainly the TRC reports. The book ends with a quote from the TRC’s final report:

“Reshaping national history is a public process, one that happens through discussion, sharing and commemoration…. Public memory is dynamic – it changes over time as new understandings, dialogues, artistic expressions and commemorations emerge.”

St. Michael’s Residential School: Lament & Legacy is available for purchase at Amazon and other booksellers. In the acknowledgements, Dyson and Rubenstein note that a portion of the royalties received for the book “will be donated to Reconciliation Canada and the Indian Residential School Survivors Society.”