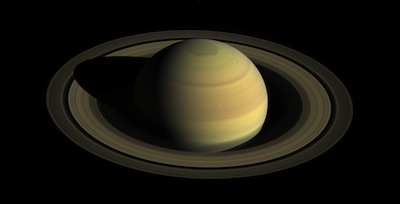

Saturn’s main rings, along with its

moons, are much brighter than most stars. As a result, much shorter exposure

times (10 milliseconds, in this case) are required to produce an image and not

saturate the detectors of the imaging cameras on Cassini. A longer exposure

would be required to capture the stars as well. (photo from NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space

Science Institute)

Grand Finale was the official name of Cassini’s last act: a risky orbit between Saturn’s rings and atmosphere in an attempt to explore the planet up close, right before the craft went up in flames.

Prof. Yohai Kaspi and Dr. Eli Galanti of the Weizmann Institute’s earth and planetary sciences department led one of the studies on Cassini’s final mission, revealing the depth of Saturn’s jet streams – the strongest measured in the solar system, with winds of up to 1,500 kilometres per hour – and found them to reach a depth of around 9,000 kilometres. Teaming up with research partners in Italy and the United States, their study also helped reveal the age of the planet’s rings. The findings of these studies were published this month in Science.

Cassini was one of the more successful planetary missions, orbiting and returning information on Saturn and its moons for the last 20 years. As the mission was approaching its end, it was decided to end its life with a non-circular orbit swinging in very close to the planet, followed by a final plunge into the gaseous mass. Kaspi and Galanti joined the Cassini team following their work as part of NASA’s Juno science team, which had employed a similar orbit to produce the most reliable measurements yet of Jupiter’s atmospheric depth. The Cassini scientists thought it would be possible to do the same for Saturn, and the Weizmann scientists were called in to apply their methodology to the Saturn measurements.

Kaspi described the challenge: “We detect small variations in the gravity field as the craft orbits Saturn, and translate these into the atmospheric wind that produces them. There was no guarantee it would work for Saturn, as the gravity signal on Saturn is more difficult to interpret than what we had on Jupiter. We discovered that not only did it work for both planets, but that same physical processes control the depth of the flows on these two planets.”

To calculate the depth of the winds, the gravity measurements undertaken by Cassini were analyzed with the theoretical model developed by the Weizmann researchers. “We also teamed up with a second group investigating the internal structure of the planet,” said Galanti. “Together, we calculated that the depth of the atmosphere is up to around 9,000 kilometres. That is three times deeper than that of Jupiter. We also found that, just as on Jupiter, a strong internal magnetic field is what limits the depth of this layer of the atmosphere. Our theory worked twice, which provides strong support for its validity.”

In the same study, the researchers analyzed the Grand Finale data from Saturn’s rings, finding they are at most 100 million years old. That is quite recent in the 4.5-billion-year history of the solar system. The planet in the night sky at the time of the first dinosaurs was, apparently, without the rings we know today.

For more on the research being conducted at the Weizmann Institute, visit wis-wander.weizmann.ac.il.

– Weizmann Institute

Saturn losing its rings

New NASA research confirms that Saturn is losing its iconic rings at the maximum rate estimated from Voyager 1 and 2 observations made decades ago. The rings are being pulled into Saturn by gravity as a dusty rain of ice particles under the influence of Saturn’s magnetic field.

“We estimate that this ‘ring rain’ drains an amount of water products that could fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool from Saturn’s rings in half an hour,” said James O’Donoghue of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Md. “From this alone, the entire ring system will be gone in 300 million years, but add to this the Cassini-spacecraft measured ring-material detected falling into Saturn’s equator, and the rings have less than 100 million years to live. This is relatively short, compared to Saturn’s age of over four billion years.” O’Donoghue is lead author of a study on Saturn’s ring rain appearing in Icarus Dec. 17.

Scientists have long wondered if Saturn was formed with the rings or if the planet acquired them later in life. The new research favours the latter scenario, indicating that they are unlikely to be older than 100 million years, as it would take that long for the C-ring to become what it is today assuming it was once as dense as the B-ring. “We are lucky to be around to see Saturn’s ring system, which appears to be in the middle of its lifetime. However, if rings are temporary, perhaps we just missed out on seeing giant ring systems of Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune, which have only thin ringlets today,” O’Donoghue added.

Various theories have been proposed for the ring’s origin. If the planet got them later in life, the rings could have formed when small, icy moons in orbit around Saturn collided, perhaps because their orbits were perturbed by a gravitational tug from a passing asteroid or comet.

– NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre