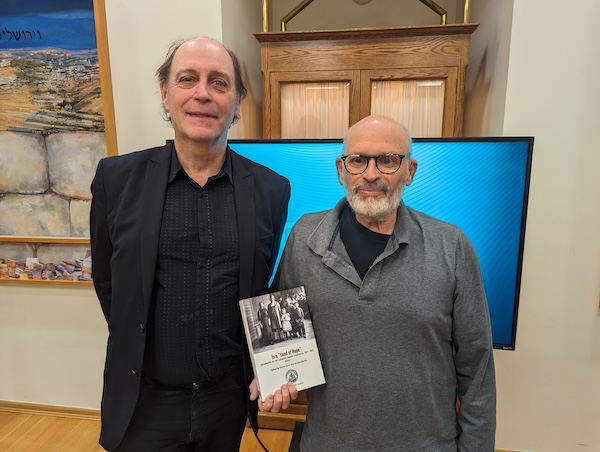

Pierre Anctil, left, and Richard Menkis with a copy of their new book, In a “Land of Hope”: Documents on the Canadian Jewish Experience, 1627-1923. (photo by Pat Johnson)

The first Jew known to have set foot in what is now Canada was Esther Brandeau, who arrived in Quebec City in 1738. Jews were forbidden from migrating to New France, but the young woman’s religion was not the only thing she was concealing. She was also dressed as a boy.

Interrogated by authorities on arrival, Brandeau was the subject of high-level consultations before she was sent back to France the following year.

Although they are certain there were Jews in the land that would become Canada before 1738, professors Richard Menkis and Pierre Anctil say Brandeau’s case is the first documented proof of a Jewish presence here.

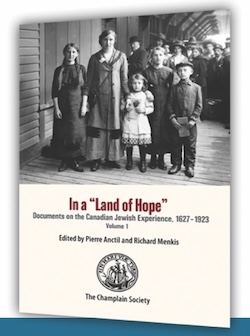

The historians shared Brandeau’s story at a book launch in Vancouver Nov. 21, following the annual general meeting of the Jewish Museum and Archives of British Columbia. Menkis, an associate professor in the departments of history, and classical, Near Eastern and religious studies at the University of British Columbia, and Anctil, a University of Ottawa history professor, co-edited In a “Land of Hope”: Documents on the Canadian Jewish Experience, 1627-1923.

The book spans three centuries through the lens of more than 150 documents, many of them never before published.

Menkis emphasized the efforts made to provide geographical diversity in the volume.

“If we want to appreciate the Canadian Jewish experience, we’ve got to move beyond – believe it or not – the borders of Quebec and Ontario,” he told the audience at Temple Sholom. “We have offered texts that represent the experiences from west to east. We offer an excerpt from the minute book of Congregation Emanu-El, in Victoria, recording a debate on whether to include the Freemasons in a cornerstone-naming ceremony. We have documents from the other ocean, from a controversy in Halifax, where the local SPCA argued that kosher slaughtering was cruel and that the local shochet (kosher slaughterer) was accordingly charged.”

Anctil, who is francophone, emphasized the uniqueness of the Jewish experience in Quebec and noted that shared interest between Catholics and Jews led to one of the first legislative acts of Jewish emancipation in pre-Confederation Canada. In 1832, the legislature of Lower Canada (later Quebec) passed a statute making British subjects who are Jewish equal under the law to all other British subjects in the jurisdiction.

“It’s a foundational document,” said Anctil. “It’s the first time that Canada and most British colonies allowed Jews to have political and civil rights.”

The motivation may have had less to do with Jewish rights – there were only about 150 Jews in colonial Canada at the time – than self-interest among French Catholics.

“They were Catholics living in a Protestant world and they knew that, if the Jews had more rights, the Catholics also had more rights,” Anctil said.

The Quebec education law of 1903 had lasting impacts on the province, especially for Jews and their place in the “distinct society.”

“The Quebec government decided that Jews would be considered Protestants for the purpose of education,” said Anctil, “and [Jews] were all sent to the Protestant school board of Montreal and did not receive a Catholic or French education, which proved problematic in the decades ahead.”

Brandeau, the young Jewish woman who tried to masquerade as a non-Jewish boy, was only the first documented case of Jews coming up hard against Canada’s explicitly or implicitly racist immigration laws. The theme runs through the 400-page book.

Canadian immigration policies reflected the agricultural dominance of the Canadian economy into the 20th century and, since most European Jewish migrants were not farmers, this was an inherent, if not unwelcome from the perspective of immigration officials, bar to many Jews.

The editors address Jewish farmers in the book – those who had experience in the Old Country as well as those who, successfully or less so, took to the land after migration – but prioritize the economic experiences of Jews in peddling, retail and the garment industry.

The editors address Jewish farmers in the book – those who had experience in the Old Country as well as those who, successfully or less so, took to the land after migration – but prioritize the economic experiences of Jews in peddling, retail and the garment industry.

The preference for immigrants with farming backgrounds was an implicitly, possibly even unintentionally, anti-Jewish component of Canada’s immigration approach. Other examples were less subtle. It was not so much that legislation said Jews were not permitted to migrate, but that unwritten rules, “administrative refinements” or policies that were open to interpretation could be used to block Jews from entering the country.

There had been rumours of a deliberate anti-Jewish immigration policy, and Menkis said their research found evidence that instructions had been sent to immigration officials in Europe that Jews were to be considered undesirable applicants.

In 1923, an order-in-council was passed by the federal cabinet, which said that only farmers, farmworkers and domestic women servants would be allowed to immigrate to Canada, effectively closing the door to Jews and many other communities from the Balkans and Eastern Europe.

Anctil and Menkis pointed out that Jews were far from the only group excluded under Canada’s immigration policies.

“Asians and Africans – out completely,” said Anctil. “Almost nobody got in. In 1923, we have the Chinese Immigration Act, which made it extremely difficult for financial reasons for Chinese people to migrate to Canada. So, we had a really racist immigration policy until the ’60s, ’70s. Not just Jews.”

Many of the documents included in the book were translated into English by the editors, from the original French, Yiddish or Hebrew.

“It’s very important to work in four languages,” Anctil said. “English, French, Yiddish and Hebrew – there is no way of doing Canadian Jewish history if you leave one out. All these four languages are represented in the book and serve an essential purpose of allowing the full flavour of this story to be told.”

The pair’s decade of research for In a “Land of Hope” uncovered some unexpected treasures.

“Usually, we hear of social welfare from the minute books of established members of the community and their organizations,” said Menkis. “I was reading one of these minute books on one occasion in Toronto when a piece of paper dropped out.”

It was a desperate appeal from a woman seeking help from a Jewish women’s aid organization, specifically asking for chickens for the Passover seder.

“Please let me know if you’re going to send me the Paisez [Pesach] order and if you’re going to send me what you promised me,” read the handwritten letter. “I hope that you’re going to be kindly for my sick husband and my six little children because I just leave it to you and you should help because there is nobody to help accept [sic] you. I hope you won’t forget us and send us an answer right away. Because I could not tell you very much & That is the first time in my life that I should ask for help. But everything can happen in a lifetime. Yours […] Mrs. Green.”

The book closes in 1923 because that was a turning point in Canadian Jewish history and in the larger story of Canadian immigration. As a result of an economic depression following the First World War, nativist sentiments led to what was an effective end to large-scale immigration into Canada, itself a response to a parallel development south of the border.

“One of the reasons it happened in Canada was that they knew the Americans were closing down [open immigration] and they didn’t want to get all those Jews that the Americans weren’t accepting,” said Menkis.

A second volume of the work, picking up from 1924, is due to be released in 2026. Anctil said the unique experiences of Jews in Quebec will be even more pronounced in that book.

“The Jews living in Quebec faced a different situation than Jews living elsewhere,” he said. “The majority of [Canadian] Jews were in Quebec until the ’60s and it’s not only the French and Catholic issue, it’s the issue that the school system was separated between Catholics and Protestants and Jews could not find a place easily in the public school system.”

Bias against Jews also has a different strain in each of Canada’s official linguistic communities, Anctil added.

“Antisemitism among the French is not the same as among the British,” he said. “The logic’s not the same and the results are not the same. Often, when you read histories of Canadian Jewry, you have the impression antisemitism is all the same, whoever is antisemitic. It’s not true. [There are a] number of subtleties and complexities in that.”

In a “Land of Hope” was released by the Champlain Society, a publisher of scholarly Canadian books. This is the first book the society has published about a community that is not French or English in its 115-year history.

“I hope at least I’ve convinced you of the value of the book, without being crassly commercial,” Menkis said at the end of the presentation, adding: “Although, I do want to say that In a ‘Land of Hope’ would make a great Hanukkah gift.”