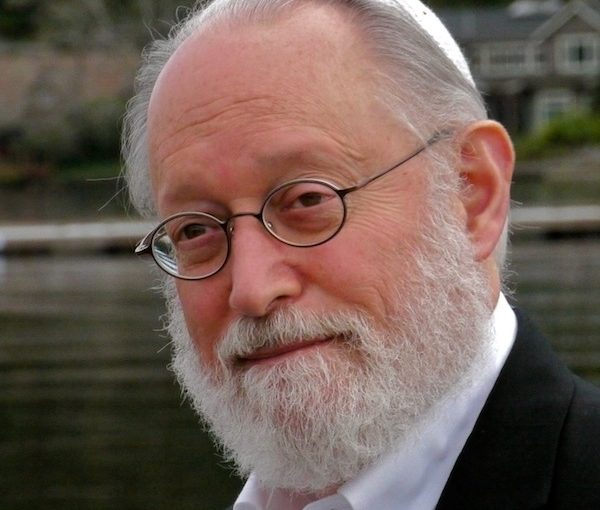

Michael Geller at the groundbreaking of ConWest’s IRONWORKS development in 2017. (photo from Michael Geller)

The COVID pandemic and the months of social isolation it created will have impacts on real estate prices, urban design and human behaviours, says a local expert. But the changes are not likely to be revolutionary so much as accelerate trends already underway.

Michael Geller, an architect, planner, real estate consultant and property developer, spoke to the Temple Sholom Men’s Club in a virtual event via the meeting platform Zoom May 25. (For more on the club, click here.) Geller is also adjunct professor in Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Sustainable Community Development and a longtime leader in Jewish communal organizations. His topic was Real Estate in the Era of COVID.

“Housing sales are down significantly and are as low as they have been in recent memory,” he said. Wages have been dramatically impacted for an enormous number of individuals and household debt is increasing significantly. Many renters are unable to meet their payments.

Housing sales are affected by the obvious issues of economics, but also because buyers and sellers are reticent about the physical interaction required in the process of viewing potential homes. Sales have not entirely collapsed, though, he noted.

“There are still some bidding wars for more affordable condos, priced under $700,000,” said Geller, adding: “Can you imagine 30 years ago being told that affordable condos would be under 700,000? It just shows you what has happened to our market in recent years.”

While sales are down, there has not been a significant increase in the supply of either listings or new homes coming to market, he said. “So, at the moment, we aren’t seeing the dramatic drop in prices that many assumed, myself included, would occur.”

What may occur is a stalling of new construction because lenders are cautious. “They don’t want to lend money for anyone to buy land at the moment,” he said. “This is a significant factor.”

While there were many years when there was almost no purpose-built rental housing created, this has shifted, with about 4,000 new units this year in the city proper and 9,300 in Metro Vancouver. This supply, combined with the economic challenges brought about by the pandemic, have had impacts on rental rates. “For the first time in a long time, we are starting to see a softening of rent,” he said.

Foreign investment has been credited with playing an outsized role in property values in recent decades and some commentators speculate that buyers may be “circling like vultures” in the event of comparative real estate bargains in British Columbia, he said.

Geller noted the opposite could occur, however, as the market softens. “Some of the people who came, especially from mainland China but also Hong Kong and Europe, might actually divest themselves of their investments and pull out of the Vancouver market,” he said.

International events will also likely play a role. Uncertainty and upheaval around changes in China’s governance of Hong Kong could make Canada very appealing, especially to the 300,000 residents of Hong Kong who have Canadian citizenship.

“We have a high level of personal safety and, when you think about it, that is one of the most important considerations,” he said. “You can have all the money in the world but if you don’t feel safe in your home at night, you may not necessarily stay in that home.”

British Columbia’s recognized success in dealing with the pandemic has enhanced its international image. “As we start to focus more and more on health issues, that cannot be ignored,” he said.

Foreign investment in Vancouver has dropped significantly since the implementation of the foreign buyers’ tax.

“Will those foreign buyers come back, even if they have to pay 20% premium?” Geller asked. “If they don’t come back, and if that means local developers decide not to build, whether it be rental or condominiums, and we start to see significant unemployment of all those construction workers … then it may well be that the government says, you know, this is a difficult situation, these are unprecedented times and maybe they’ll just decide that, for the next two years, the foreign buyers tax will be reduced to five percent rather than 20% in order to stimulate the economy.”

On the commercial real estate front, the experience of working from home may change our relationship to the office. If people continue working remotely, that could reduce demand for office space. On the flip side, new ideas of personal space and social distancing could mean that people come to expect fewer workers in more space, thereby increasing demand.

If more people do opt for remote work options, some may choose to move to more affordable and remote locations. Home design might adapt to include formal workspaces so that people aren’t using kitchen counters as desks. Condo towers and apartment buildings might opt for hotel-style shared business centres rather than spas. They may move toward more “touchless tech” – a familiar example being the Shabbat elevator.

As stores reopen, retailers may see a decline in shoppers, but Geller suspects that warehouse space is headed for a bull market. “As more and more people are buying online, there is a need for more and more warehouse space to store all this product before it’s delivered,” he said. “This applies not just to clothing and giftware, it applies to food and other goods that are stored in cold warehouses.”

Looking at social changes that have resulted from pandemics in previous centuries, Geller said, “One of the things that came out of [earlier pandemics] was an appreciation of the need for more parks and green space throughout the cities. Central Park in New York, that was created by the New York City Board of Health because of the belief that this would lead to improved human environmental health for everybody in the city. In most European cities and many other American cities, large parks and green networks were created to help people lead healthier lives.”

Improved sanitation, water supply and sewage treatment systems were also at least partly a result of these catastrophes. Home design changed, including the advent of sleeping porches, based on the understanding that fresh air was preferable to stuffy interiors. The modern bathroom, including the proliferation of white tiles that both made it easier to clean and added to the perception of sterility, emerged. Wooden toilet seats, which were the norm, were replaced by plastic ones.

“The powder room became a creation in a larger house because the man who came to deliver the coal or to deliver the ice, you didn’t want them going through your house using your bathroom, so powder rooms became popular,” he said.

Though he had plenty of ideas, Geller was emphatic that he didn’t really know what the future holds. But he has some confidence about a general forecast.

“Often,” he said, “pandemics and similar sorts of events accelerate changes that were already happening.”