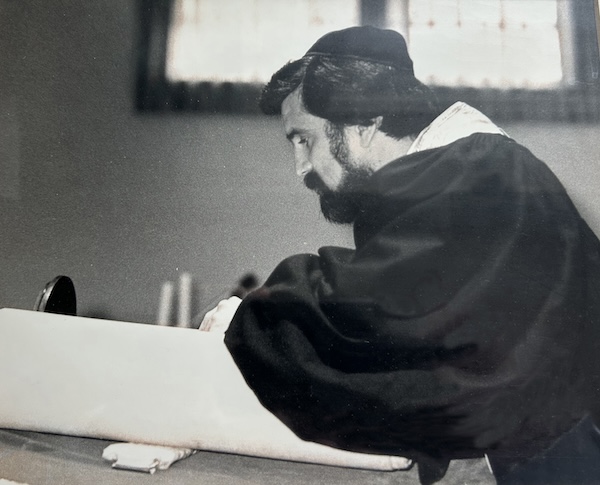

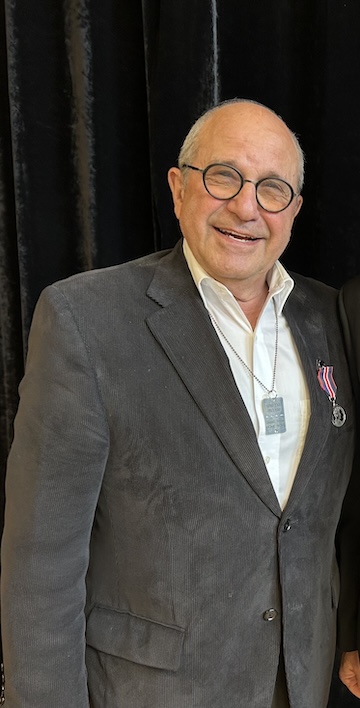

Parm Bains, incumbent MP and Liberal candidate in Richmond East-Steveston, and his Conservative opponent, Zach Segal, spoke at Beth Tikvah April 15. (photo by Alan Marchant)

Liberal and Conservative candidates made their pitches to the Jewish community in a candidates’ forum at Beth Tikvah Congregation April 15.

Parm Bains, incumbent member of Parliament and Liberal candidate in the riding of Richmond East-Steveston, and his Conservative opponent, Zach Segal, who hopes to unseat Bains as MP on April 28, shared their visions, and those of their parties, to a crowded sanctuary at the Richmond synagogue.

Both candidates spoke of their lifelong roots in Richmond.

Bains explained that his engagement with at-risk youth and combating gang violence first emerged through coaching sports. He became a community liaison for the provincial government under premiers Gordon Campbell and Christy Clark.

Segal worked in Ottawa during the Stephen Harper administration for the ministers of defence and transportation. He credited the former Conservative government for making Canada a “moral compass in the world.” However, he suggested that Jewish Canadians are wondering if there is a better tomorrow in Canada, not just because of rising antisemitism, but because of challenges around housing, affordability and community safety.

On the issue of antisemitism, Bains pointed to his Liberal colleague Anthony Housefather, who is the government’s special advisor on Jewish community relations and antisemitism, and urged members of the community to ensure authorities are made aware of every incident of antisemitic bias and hate.

“You have to report it,” Bains said. “If it’s reported, it’s a data point that we can take action on.”

Both candidates spoke of the challenges in enforcing existing anti-hate laws.

Bains said it is crucial that police understand the definition of hate crimes and that they are educated to enforce the laws as they stand.

Segal condemned an “explosive rise in antisemitism” and credited it in part to “a horrible lack of moral leadership.” The intimidation of Jewish people and the employment of incendiary language has been tolerated by federal leaders and others on the basis of free expression, he argued.

“This is hate speech,” Segal said. “This is inciting hate and it is illegal.”

Police have said they don’t have the support to go after perpetrators, said Segal, adding that funding to increase security at Jewish institutions, for example, is a Band-Aid solution that deals with the symptoms and not the causes. He said that his party’s leader, Pierre Poilievre, has been “rock solid” in condemning hate rallies and marches. He said that a Conservative government would “close loopholes” that allow hateful events like the annual Al-Quds Day rally in Toronto to continue unchecked.

Existing laws need to be enforced, said Bains, and he suggested there is a need to understand why police are not calling for charges and Crown prosecutors are not pursuing them.

“Why is there a reluctance?” Bains asked. “Where does that leadership need to come from?”

Canada has seen some of the “most obscene” anti-Israel activism of any Western democracy, Segal asserted, citing Charlotte Kates, who was arrested in November, and her Samidoun Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network, which had been declared a terrorist entity shortly before her arrest, “years after Jewish and other community leaders sounded the alarm on them,” Segal said.

Segal also took exception to the fact that Canada instituted a military embargo on Israel before it recognized the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps as a terrorist organization.

“We were literally being tougher on Israel than Iran,” he said.

Bains said Israel has a right to defend itself and the hostages need to be freed. Canadians, however, want to play a role as “honest broker” and in peacekeeping. “Right now, Canadians want to see the violence stop, the bloodshed stop,” he said.

Segal condemned the Liberal government for resuming funding for UNRWA, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency that functions as a quasi-governmental body in the Palestinian territories, some employees of which participated in the Oct. 7 pogroms.

“That is out of step with our allies in the Western world,” Segal said. Where the Harper Conservative government voted against one-sided resolutions of the United Nations, under the Liberals, said Segal, Canada has again begun supporting demonizing resolutions against Israel.

Both candidates called for more affordable housing, supports for seniors and economic opportunities for young people.

The candidates asked to speak were selected based on independent polling information which showed the Liberals and Conservatives to be the two parties leading or competing in both Richmond ridings. The Beth Tikvah Community Awareness Committee, which sponsored the event with support from the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs and the Canadian Jewish Political Affairs Committee, chose to give those candidates likely to form government or be in the official opposition the opportunity to address the issues.

Rabbi Susan Tendler opened the event with reflections on reconciliation and noted the significance of the event taking place during Passover, the celebration of freedom, while Jews remain captive in Gaza.