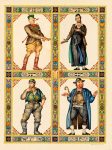

“The Four Sons,” Arthur Szyk, 1934. According to Wikimedia, Szyk “originally intended his Passover story of persecution and deliverance (told through the traditional text of the Haggadah) to be a strong statement against the Nazis, but no publisher in his native Poland dared take on a project with strong anti-Nazi iconography. He ultimately found a publisher in England. This image of the Four Sons … depicts the Wicked Son as an assimilated German complete with porkpie hat and Hitler mustache.” (image from From Arthur Szyk Society, Burlingame, Calif.)

The significance of the seder’s Four Questions should not be confined to being a concrete educational tool for the purpose of teaching historical information to children having a limited sense of abstraction and who bore easily. The questions are a characteristic of the adult intellectual culture during the time of the rabbis.

In the Mishnah, the child is the one who asks and the parent teaches, but, in the Talmud, another source is quoted that requires the adult to ask questions of him or herself: “Our rabbis taught: if his child is intelligent he asks him, while if he is not intelligent his wife asks him; but if not, he asks himself. And even two scholars who know the laws of Passover ask one another.” (Babylonian Talmud, Pesachim 116a)

Here the point is not to recount the story of the Exodus to children, but rather to create a dialogue of questions and answers among adults. The questions of the wise child may be thought-provoking to his or her parents; similarly, the questions of one colleague would be of interest to another. Someone who knows all the laws of Pesach is still required to ask questions, and scholars on their own at the seder are required to ask themselves questions. Why?

At a certain level, the questions serve as an external pretext to refresh the memory in order to raise the level of consciousness concerning the Exodus, even for those who have passive knowledge of the information. At another level, someone who asks himself or herself questions and then answers them, can delve deeper and discover new aspects of knowledge.

This is the educational method practised in the Lithuanian yeshivot – two students on the same level study the text by asking each other questions, raising hypotheses and debating the issues, without hearing lectures from a teacher “who knows the answers.”

This is common practice in universities, where a researcher finding himself or herself at an impasse takes a walk alone while conducting an internal dialogue, which may culminate with new insights into a subject with which s/he is very familiar. The question is a powerful tool for the advancement of the thinking of both the one who asks and answers it.

The rabbis identified a particular type of question, known as a kushiya. A kushiya queries a practice that contains an internal contradiction or which runs contrary to other authorized sources. Unlike the kushiya, an ordinary question generally begins with the word “what,” for example, “What time is it?” It is as if the object of the question has something, information, that the one asking the question needs, and that the one asked “lends” out (literally, sh’ayla, in Hebrew).

The formulation of the kushiya is more sophisticated: “One would expect that such a thing would happen or be written, but why has something else, something unexpected happened or been written?” The poser of the kushiya comes equipped with information and expectations for a certain world order, and this makes him or her aware of deviations, contradictions and the disappointment of expectations. “How is this night different from all other nights – on all other nights we eat leavened bread and matzah, but on this night we eat only matzah?”

The one posing the kushiya sees the whole picture and has expectations of a rational world order. That is why any contradiction requires a rational explanation. We might expect that the more one learns, the fewer questions s/he might ask, after all, s/he already has so much information. But the true intellectual will pose ever more kushiyot, because s/he is all the more aware of the complexity of the world, which is arranged according to so many principles. Curiosity is increasingly aroused and that is why the wise child is the one who asks the kushiyot of his or her own volition, while the younger children need the help of the parent to ask even the simplest question.

Paradoxically, the search for rationality is sustained by the unusual and not by the regular orderly routine. People do not query that which can be taken for granted, even if the explanation is unknown. For example, based on the experience of many Pesachs and seder nights, to the adult Jew, the youngest child asking the Four Questions is taken as a matter of course. But as soon as s/he discovers a different version of the questions, such as the one we saw in the Mishnah, s/he asks “Why do we ask these questions and not others? What is the reason?” or “Why does the Mishnah say the parent says Ma Nishtanah rather than the child?”

The search for rationality in our familiar world is sustained by the ability to imagine alternatives to the existing order. There is a set introduction to the midrashei halakha, homiletic interpretations and inferences of the rabbis (in the Mekhilta). It involves the raising of a hypothetical question, as in this example from the Haggadah. The rabbis wondered:

“You shall tell your child on that day: ‘It is because of this, that the Lord did for me when I went free from Egypt.’” Could this verse mean that you should begin to tell the story at the beginning of the month (in which the Exodus occurred)? No, for the verse explicitly states “on that day” (of the Exodus). Could that mean that we start when it is still daytime? No, for the verse explicitly states: “because of this.” “This” refers to matzah and maror laid before you (only on seder night) (Mekhilta).

“This” implies that the parents must point at the matzah and maror, and use them as visual aids to tell the story (Rabbi Simcha of Vitri).

“Could this verse mean” introduces an imaginative, alternative hypothesis based on the biblical text. “No, for the verse explicitly states that” is a strict construction of the meaning of the existent version of the text that neutralizes the feasibility of an alternative suggestion.

Indeed, the midrashei halakha ask even when no additional version has been found, and only an imaginative person could envisage other reasonable possibilities. There is no attempt here to undermine the accepted text or religious practice, but rather to understand what lies behind it.

If so, then the study method of the rabbis is seemingly founded on a paradox. In order to understand the reasons for the existing order of the customs or the words of the biblical text, we must be able to conceive of another order based on alternative logic. Only that which is not self-explanatory and is not accepted blindly as tradition can lead to a process of thought and discovery of the rationality it contains. The ideal scholar in the culture of the rabbis is not an authoritative figure acting on the basis of a simplistic faith who accepts basic premises without question.

Noam Zion has been a senior research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute since 1978, and he teaches in Hartman Institute rabbinic programs. He also works with the Muslim Leadership Institute, the Hevruta gap-year program for Israeli and American Jews, and the Angelica Ecumenical Studies program in collaboration with the Vatican University Angelicum in Rome. He has developed study guides on Bible, holidays and rabbinic ethics, has numerous publications to his credit and lectures worldwide. Articles by Zion and other Hartman Institute scholars can be found at shalomhartman.org.