According to the Babylonian Talmud (Eruvin 53b), the Hebrew-speakers of ancient Judea were so precise in their speech that they would never describe a cloak they were trying to sell as merely green, but would tell you instead that it was the colour of newly sprouted beet greens trailing along the ground. Galileans, on the other hand, were less punctilious:

“What do you mean when you say that Galileans are not careful in speaking? It is taught: There was a Galilean who used to go about [the marketplace] asking, ‘Who has amar? Who has amar?’ They said to him, ‘Stupid Galilean, do you mean khamor [donkey] to ride or khamar [wine] to drink? Amar [wool] to wear or imar [a lamb] to slaughter?’ And don’t forget the woman who wanted to say to her friend, ‘to-i de-okhlikh khalovo, come, I’ll give you some milk,’ only to have it come out as ‘tokhlikh lovya, may you be eaten by a lioness?’”

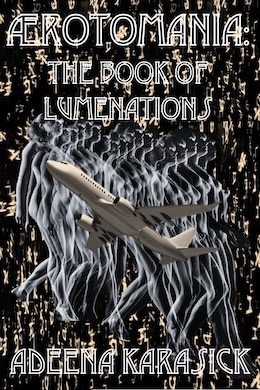

Where the ancient Galileans seem to have had no choice but to sound like themselves, Adeena Karasick has elaborated, over 14 volumes of poetry, a sort of deliberate neo-Galileanism that sometimes bridges, sometimes leaps and, on occasion, just fills the talmudic chasm between utterance and meaning in a way guaranteed to drive any artificial intelligence program out of its simulated mind. As she says in the poem “Talmudy Blues II” that is dedicated to me in her new collection, Aerotomania: The Book of Lumenations (Lavender Ink): “… sometimes the letters rule over her / and sometimes she rules over the letters / cleaving to the light of infinite possibility.” (p.31)

Is Karasick cleaving to the light as she rules over the letters? Or do the letters ruling her do the cleaving? Have her consonants been endowed with the naissances latentes of Rimbaud’s “Voyelles”? Or, less goyishly, is Karasick turning Galilean imprecision into an aesthetic approach rooted in the modalities of elementary-level reading instruction – reading silently and reading aloud, the absorption and subsequent re-citation of a written text – as enacted in the traditional East European Hebrew school known as kheyder?

Is Karasick cleaving to the light as she rules over the letters? Or do the letters ruling her do the cleaving? Have her consonants been endowed with the naissances latentes of Rimbaud’s “Voyelles”? Or, less goyishly, is Karasick turning Galilean imprecision into an aesthetic approach rooted in the modalities of elementary-level reading instruction – reading silently and reading aloud, the absorption and subsequent re-citation of a written text – as enacted in the traditional East European Hebrew school known as kheyder?

The basic level of instruction had three phases:

1. Alef-beys, literally, alphabet, in which students learn to recognize the consonants that make up the Hebrew alphabet, along with the sundry diacritical marks that take the place of alphabetic vowels. There are 11 of the latter, representing five vowel sounds.

2. Halb-traf leyenen, reading half syllables. Each diacritic is run, as it were, through all 22 of the consonants. So, for example, syllables formed with the vowel komets would be learned by reciting, “Komets alef, o; komets beys, bo; komets giml, go” … and so on, to the end of the alphabet, when the student would go on to the next vowel: “Pasekh alef, a; pasekh beys, ba; pasekh giml, ga.”

3. Gants-traf leyenen, reading whole syllables, i.e., combining the individual letters or syllabograms into words.

Karasick’s traffic is with the last two, the kheyder basics supplemented by the graphemically focused mysticism of Sefer Yetsira and Abraham Abulafia as refracted through a contemporary sensibility and range of reference: “The letter is matter which moves matter … these words are closer than they appear.” (p.31)

We see halb-traf in full flight in, say, the coda to “Eicha,” the long poem with which Lumenations opens: “In the eros of aching ethos / The caesura screams – / Through cirque’elatory sequiturs, resistances” and continues: “Here, her / in mired err / whose scar is clear // Hear her/here/whose heir / wears err’s // shared prayer / where // care is rare….” (pp.26-27)

All you have to do is imagine a phrase like “hear her/here/” in unvocalized Hebrew, רה רה רה, and then read it as “hair hare hoar,” to realize that Karasick’s poetry, like the airplane she anatomizes in Aerotomania, constitutes “a hybridized syncretic space between cultures and idioms / where that interlingual complexity doesn’t close down but builds dialogue” (p.83), a dialogue rooted in, but quickly soaring beyond, quotidian phonemic reality.

There is an upward thrust to the book, from the dust and cracked earth of “Eicha,” the recasting of the biblical Lamentations (eicha means how, as in, “How sits the city solitary”), through the rising rabbinic commentary of “Talmudy Blues II,” a romp through ways of thought – words, that is – that now stand in place of the things destroyed: Jerusalem and the Temple (known in Hebrew as the Holy House).

An excursus on the idea of house follows, then “Checking In II,” i.e., checking into the Aerotomania flight by stowing readers’ cultural baggage for the duration of their stay on the plane. Having shaken off our dust (Isaiah 52:2), we emerge from the fog of our associations. Our lumen is come (Isaiah 60:1); we rise through the ether to embrace The Shining.

As the dedicatee of “Talmudy Blues II,” it behooves me to say something about the poem. A continuation of “Here Today Gone Gemara” from Karasick’s 2018 collection Checking In (Talonbooks), “Talmudy Blues II” consists in large part of elaborations of dialogue (and dialect) culled from our ongoing conversations about the ways in which the Talmud is reflected and refracted in Yiddish. “Carpe verbum,” reads the epigraph to “Here Today” – pluck that word like it’s a Sabbath chicken, clear away the excrescences and bite into the thing itself, ever mindful that the Hebrew davar means both word and thing, utterance and entity; my honeyed words solidified into raw material, ore for Adeena’s gold, one davar turned into another. But, as it says in the Talmud (Megillah 15), “Whoever credits a davar to the person who said it brings redemption to the world.”

Amen. Thou hast conquered, O neo-Galilean.

Michael Wex is author of three books on Yiddish, including Born to Kvetch. His songs have been recorded by such bands as the Klezmatics, and he has translated The Threepenny Opera from German into Yiddish. His one-person shows include Sex in Yiddish, Wie Gott in Paris and Gut Yontef, Yoko. I Just Wanna Jewify: The Yiddish Revenge on Wagner was recently revived (on Zoom) by the Ashkenaz Festival. His most recent major project, Baym Kabaret Yitesh, a recreation of a 1938 Warsaw Yiddish cabaret, was the surprise hit of Ashkenaz 2022 in Toronto. Bas Sheve, the long-lost Yiddish opera restored by Wex and composer Joshua Horowitz, was the not-so-surprising hit of the same festival. This book review was originally published in New Explorations: Studies in Culture & Communication, Vol. 3, no. 2 (2023).