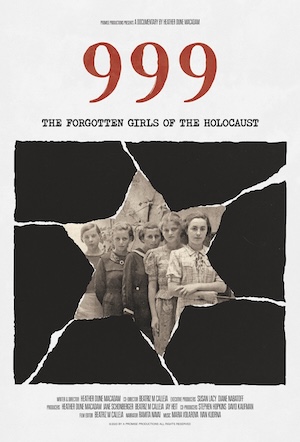

In February, I attended the Canadian première of the movie 999: The Forgotten Girls, directed by Heather Dune Macadam, who also wrote the book on which it is based, 999: The Extraordinary Young Women of the First Official Transport to Auschwitz. Screened at the Rothstein Theatre, the documentary was presented by the Vancouver Jewish Film Centre.

This is a brilliantly made movie, which combined clips from home movies, historic film footage and photos, interviews with survivors and others, Slovak folk songs, and more. The movie explained how the Hlinka Guards (Slovak militia) rounded up young, unmarried Jewish girls from small towns in eastern Slovakia. The Jewish girls from the city of Humenné were put on buses and transported to the city of Poprad, where they were put into military barracks. On March 25, 1942, when the number of girls reached 999, they were put into a cattle-car train and left Poprad and their native Slovakia for an “unknown destination.” The train went into the Third Reich for “volunteer work.” This was the first transport to Auschwitz. Most of these girls died there.

I heard a similar story from my mother, Klara (Tamara) Kulkova, who was born in northern Slovakia, in the town of Zilina. She remembered that, in the summer of 1940, she attended a Jewish camp of the Maccabi movement, and that she enjoyed that summer very much with her classmates and some older girls. She fondly remembered these days as being full of fun and laughter.

Then came the years of repression for Jews. They were not allowed to go to school or summer camp. In March 1942, my mother heard from her friends that they had received a letter, which summoned them to volunteer for a work assignment. She asked her parents for permission to volunteer, too.

At the time, nobody had any idea where these Jewish girls were going. For some reason, my mom’s father was not suspicious, despite that he had, by this time, given away his Ripper liquor-producing business to a Slovak employee for the company to continue functioning and given up the family’s spacious middle-class apartment, as Jews were forced to live in smaller accommodations. He gave my mom permission to go with her friends. So, my mom and her parents went to the gathering place in Zilina. The Hlinka Guards read the names of the invited girls and my mom’s name was not on the list. At this point, my mom asked a guard if she could join. He said, “Well, you are already here, I will add your name and you can come with your friends.”

The boys who had also been in the Maccabi summer camp decided to come help the girls with their luggage. My mom mentioned Duri Singer and I met Martin Schpitzer, who told me that the boys felt fear for the fate of these girls. They asked the guards in charge of these Jewish girls, where is this transport going? They got no answer. They also asked how long the working assignment would be, and again they did not get any answer, only smiles from the guards.

The train arrived in Poprad and the girls went into a military barrack. My mom remembers that her cousin, Erika Tellemanova, was with her, as well as some friends: Dita Linksova, Rosa Scheinbergerova, Iluska Weilova, Zuzka Policerova and Anika Grossmanova. She recalled that the military barrack did not have toilets. There was a hole in the ground, called a Turkish toilet, which they had to use. They slept on hay, on one side was Erika Tellemanova and on her other side was Rita Brownova. They stayed there for a few days, waiting for more girls to arrive from other towns, as the train out of Slovakia was, in my mom’s memory, to have around 1,000 unmarried Jewish girls on it.

In the meantime, after the boys returned, Duri Singer went straight to my grandparents and insisted that my grandfather try to get my mother out of the transport. My grandfather, Leon Kulka, listened. He then went to his lawyer and they traveled to the capital city of Bratislava, to the department of the Hlinka Guards. They met the head of the transport department and explained that they had not received a response about their application for “economically needed Jews” to be exempted from the deportations. They asked for my mom to be released and their request was granted. A telegram was sent from Bratislava to Poprad to release my mom.

My grandfather went back to Zilina and filled up his car with liquor, then traveled to Poprad to get my mother. The head of the camp said this was the first request he had received to release somebody and suggested that my grandfather take my mom and leave quickly. There was the possibility that some other Hlinka Guard would object to the release. Of course, all the liquor was left for the guards in the camp. Much later, my mom understood that the day after she left was the third transport of Jewish girls from Poprad to Auschwitz concentration camp.

After all this happened, my grandparents decided to send my mom away from Zilina, and she became a babysitter to her niece, Maya Berger, in the town of Sučany.

It took many years for my mom to be able to tell me about March 1942. It was only after the Second World War that the fate of the women transported became known. My mom lost her good friends, so she was only able to add very slowly some details about this tragic time in her life.

Helen Karsai is a retired medical doctor, who used to work at BC Cancer Agency. In the 1980s, she was a co-chair of the Western Association of Holocaust Survivors, Families and Friends. Her previous printed article was “Secrets of My Native Town,” published in the Spring 2022 Zachor, the magazine of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre.