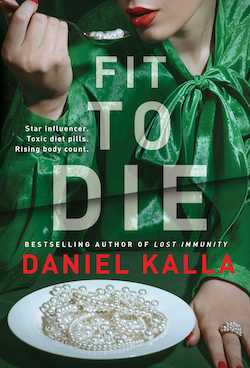

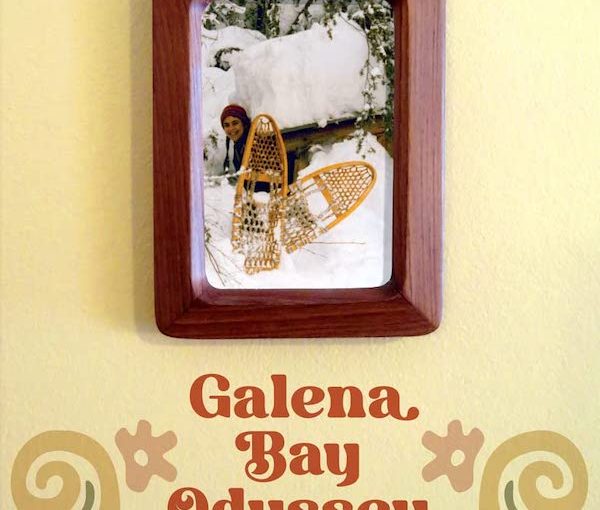

Racheal Prince, left, and Caroline Hébert in When the Walls Come Down, which is at the Rothstein Theatre Nov. 8 and 10. (photo © iiiiportraits)

“I think the performance is a really fun way to learn a little bit about Deaf culture,” Caroline Hébert, the lead actor and inspiration for When the Walls Come Down, told the Independent. “I hope people can make the time to try something different and I look forward to meeting some new people at the Chutzpah! Festival.”

When the Walls Come Down (WTWCD) will see three performances at the Rothstein Theatre next month, as part of the festival. A collaboration from Vancouver’s Dance//Novella, led by Racheal Prince and Brandon Lee Alley, the work highlights moments in Hébert’s life, “shed[ding] light on stereotypes and difficulties faced by many Deaf Canadians and tell[ing] a story of resilience and love,” according to the press material. It is performed with movement, music, projections and lighting, and in ASL with English voiceovers.

“Racheal and Brandon and the WTWCD team have been learning ASL,” said Hébert. “It’s really inspiring to me to see a group of people who want to create an environment where we can share ideas and our culture. I want to participate in more collaborations as I continue my journey as a Deaf actor. This is my first time stepping into a leading role for a one-hour show. I think, at first, I wasn’t really sure if this is something I could do. Over time, I realized that I can do it, and I can connect to many different people through my art form.”

The creation of WTWCD began in 2020, said Prince and Alley, when “our curiosity led us to explore the fusion of ASL and dance, with a strong desire to collaborate with a Deaf actor and blend their creative ideas with ours. Caroline was recommended to us by Chis Dodd, director of SOUND OFF. What intrigued us further was her last name, Hébert, which happened to be the maiden name of Racheal’s grandmother. This unexpected connection felt like a sign. After a video-translated conversation with Caroline, we realized that she possessed a compelling story that needed to be shared, so we quickly chose her as the central character for the work.”

As for her decision to be that central character, Hébert said, “I was interested in trying something new and I thought why not!? I did dance a little when I was a child so maybe that was also part of the reason?”

WTWCD debuted as a live-streamed performance during the 2021 Vancouver International Dance Festival (VIDF), which made it “challenging for us to establish a direct connection with the audience and gauge their reception of the work,” said Prince and Alley. “However, we knew this work had the potential of uplifting and illuminating a traditionally marginalized community, so we kept refining and building upon our initial ideas.”

In 2022, they received an invitation to perform WTWCD in Edmonton at the SOUND OFF festival, the first time the piece was presented in a live setting. “To our astonishment, the audience responded with thunderous stomps and a standing ovation. It was truly incredible to witness the profound connection the work had with the Deaf community,” they said.

In addition to that positive reaction, the pair won the 2023 VIDF Emerging Choreographic Award. “To us,” they said, “this award emphasized the collaborative and harmonious aspect of the work’s creation, transcending our roles as individual choreographers.”

Both creatives multitasked to make WTWCD. Prince and Alley choreographed the work; they played a part in the storyline creation and development with Hébert and her daughter, Anna-Belle Hébert, all four of whom perform the piece; Alley composed the music and Prince did the costume and set design. Other key contributors are lighting designer James Proudfoot, assistant lighting designer Chengyan Boon, and mentors and coaches Chris Dodd and Landon Krentz.

“Being a contemporary dance company, one of our goals was to find innovative ways to convey the music to a Deaf audience,” said Prince and Alley. And it was Alley who “came up with the idea of using a playful animation to advance the storyline and evoke the emotional essence of the music.

“To realize this vision, we collaborated with the Vancouver Film School,” they said. “We pitched our ideas to them, leading to the organization of a competition involving five different groups. Each group listened to our concepts and then presented us with small animations. After careful consideration, we selected the group that we believed best captured the essence of the work and the nuances of the music. They went on to create the animations that will be showcased during the performance.”

Listed on Dance//Novella’s website are producer Jill Tao, designer/animators Kanako Takashima and Cecilia Cortes, animation lead Arturo Acevedo and storyboard artist/designer Heena Yoon.

An integral part of this project has been Anna-Belle Hébert.

“She is a CODA (child of Deaf adult), fluent in ASL, QSL, English and French,” explained her mother. “Anna-Belle understands who I am and the story I want to share because it’s partly her story too. In the beginning, I recommended that Racheal and Brandon reach out to Anna-Belle to see if she would like to join the process, which they enthusiastically agreed to. In the performance, she is my voice over actor, but has also been a huge part of the creative process. She really helps bridge the gap between our ideas and how they can connect to hearing and Deaf people at the same time.”

Both Prince and Alley talk about how much they have learned while creating WTWCD. “One significant revelation for us,” they said, “was the realization that ASL and English are two distinct languages. Initially, we attempted to transcribe everything in an effort to ensure clarity, but this approach only seemed to confuse Caroline further. With the guidance of a specialized ASL coach, Caroline developed a unique method for documenting the script on paper. This breakthrough allowed her to memorize and retain everything effortlessly while making it her own.”

Prince and Alley had nothing but good things to say about Hébert.

“Caroline is an incredibly generous and patient collaborator,” they said. “During our rehearsals, we frequently paused our creative process to listen to stories from Caroline’s life. Each story offered us a glimpse into the experiences of a Deaf child, mother and student, which ultimately became the core of our creative journey. The exchange of knowledge and personal narratives became the driving force behind our work, giving it profound meaning for our team.”

When the Walls Come Down is at the Rothstein Theatre Nov. 8 and 10, at 8 p.m., and there is a special matinée for school groups grades 6 and up on Nov. 9, 11 a.m. (contact [email protected] for more information about that). The show runs 60 minutes with no intermission. For tickets, visit chutzpahfestival.com.