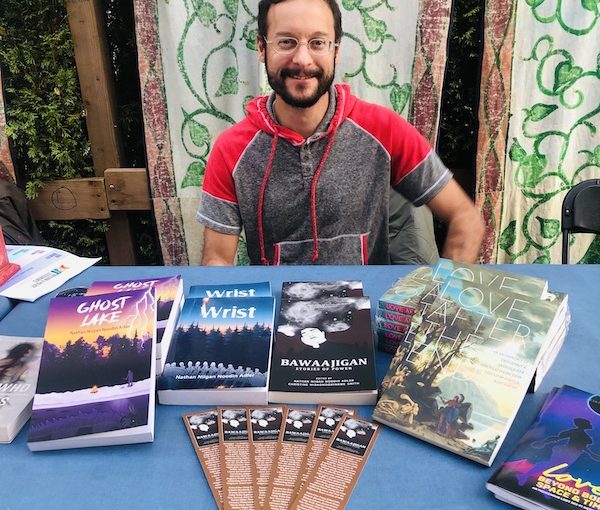

Nathan Niigan Noodin Adler at the JQT Vancouver artisan market last fall at Or Shalom for Sukkot. (photo by Carmel Tanaka)

When you enter Massy Books in Chinatown, one of the main Indigenous authors featured in the centre book aisle is Nathan Niigan Noodin Adler. I smile every time I pop in because I see signed copies of his award-winning young-adult horror fiction for sale – Wrist and Ghost Lake, both published by Kegedonce Press. Of course, Nathan would take the time to sign each book! He’s a total mensch, and we met in the best of ways.

I was having brunch with my dear friend Evelyn Tauben of Fentster Gallery at Toronto’s Pow Wow Café, owned and operated by Nathan’s brother, Shawn, an Indigenous Jewish chef. We bonded over being “Jewish&” and he mentioned that he had a sibling out west and that we should connect. So, I reached out over Facebook and we met up at the Fountainhead Pub in Davie Street Village, Vancouver’s “gaybourhood,” a few months later. Since then, Nathan has become a good friend, and you’ll also see him around JQT events, sometimes tabling as a JQT artist or just showing up to enjoy the festivities and the food.

I caught up with Nathan when he was guest curating Centring Indigenous Joy: A Celebration of Literature, Arts and Creativity with Word Vancouver for Indigenous Peoples’ Day last month. The Jewish Independent asked me to attend the event and interview Nathan for the paper.

CT: In your opening remarks, you state that you are Jewish, Anishinaabe, Two-Spirit and a member of Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation. You go on to say that your father is a Holocaust survivor and that your mother is a residential school survivor. What has the journey been like for you? How has the way you introduce yourself evolved over time?

NA: Part of my idea behind the Centring Indigenous Joy event was related to the number of emotional film programs I’ve attended that are about processing historical trauma – really important work, but also kind of a downer. Sometimes a late-night shorts program full of zombies and gore is more cathartic somehow? I wanted people to come away feeling uplifted and happy rather than heavier, you know? Especially since it was an event for Indigenous Peoples’ Day, I wanted it to be celebratory. We’re more than our trauma.

Me and two of my siblings recently traveled to Europe to work on a documentary about our great-uncle who didn’t survive the Holocaust and, after visiting so many museums, memorials, internment camps and historical sites, all I wanted to do was … party!? I insisted my brother quit his delivery job so we could spend an extra two weeks outside our work on the documentary to just have fun, do touristy stuff, go to clubs and the beach. I think balance is needed.

I don’t usually include stuff about my parents being survivors in my introductions, but I felt it was part of my thought process behind the theme for the event (Indigenous joy), and I wanted people to know it wasn’t some kind of toxic positivity in the face of harsh realities, but something that I’d deeply considered. It was more about a shift in focus.

CT: How did your parents meet? And what was their families’ reaction to their union?

NA: They met in French class at the University of Guelph in 1967. My mom missed a class and asked my dad what she missed. That’s how they started talking to each other. My mom mentioned the ballet was in town (“a leading question,” she says) and he asked her out. There were very few Native people in university at that time, so it’s pretty unlikely they [would even meet], but that’s how it happened.

My Jewish grandparents were not happy about the fact he was dating a non-Jew, at least until the babies started coming – then all was forgiven!

All my mom’s family said about it was: “Oh, he’s too old for you” [a five-year age difference], but she also probably looked much younger than him at 19 years old.

CT: Where do Jewish and Indigenous cultures meet?

NT: Food and community and tradition, though the types of foods and traditions are different. Also, the inheritance of historical trauma, and overcoming oppression. You know, just a few minor things.

CT: When did you realize that you were Jewish and Indigenous? Was there a moment?

NA: I don’t remember a specific moment. I think I always just knew? We spent most weekends either going to visit our Ojibwe grandmother or our Jewish grandparents. We did the Jewish High Holidays, Passover, Hanukkah, Purim, etc., and we went to Sunday school for awhile, and in the summer our mom took us up to the reserve or out on the powwow trail and to Native community events in Guelph, where our aunt lives; there were always feasts and ceremonies. So, we always had that grounding in our cultures, where we come from. It wasn’t always a full picture though, it was also marked by absence of knowledge, language and people – relatives who didn’t survive, the knowledge that didn’t get passed down, a lot of unknowns and absences that also becomes part of who we are. Those gaps also become markers of identity.

CT: What has been your experience of being Indigenous and Two-Spirit in the Jewish community (here in Vancouver and elsewhere)? And vice versa?

NA: Well, I think it’s been pretty great here in Vancouver, thanks to the work of JQT, which really helps build community and creates space. When I lived in Peterborough, Ont., there was also a pretty cool alternative Jewish and queer scene. I went to a memorable queer Passover there once, which is one of the few gay and Jewish events I’ve been to; a gay-Jewish-boy networking I stumbled on in Toronto once; and then the JQT events I’ve attended or participated here in Vancouver, like the arts markets and the Shabbos Queen event. And I’ve been to many Two-Spirit-specific events – my twin brother helps organize the 2-Spirit Ball in Ottawa as part of the Asinabka Festival – and, recently, I went to the 2-Spirit Powwow at Downsview Park in Toronto. It’s actually pretty great being part of these communities. Queers are everywhere, so are Jews and NDNs – add in the arts scene and social networks, and it makes it easier to find community in a new place.

CT: Your jam is horror fiction and documentary filmmaking. What draws you to these genres?

NA: I love all things horror and urban fantasy. I went through a Goth phase, and I’m still a Goth at heart. So, when it comes to making my own work, it just makes sense to work in those genres. I also picked up a lot of film and video post-production skills when I attended OCAD [Ontario College of Art & Design] University in the 2000s. But I feel like fiction isn’t for everyone. A lot of people are turned off by anything that isn’t steeped in the conventions of the here and now. They see anything with an element of fantasy, and it’s too far removed from reality – though I think the opposite is true, the fantastic can make a great metaphor for exploring the realities of this world. But some stories feel like they need to be told as they are, they don’t need any dramatization or embellishment. So, it just depends on the story. The story should dictate how it gets told.

CT: You teach post-secondary creative writing, and your work is showcased in numerous art and film festivals. What are you currently working on? What is coming up next? What’s your dream project?

NA: I’m working on a short story for a horror anthology that Kegedonce Press is planning on putting out – though the story isn’t very scary so far, so I may need to write something else. I’m curating a few panels for Word Vancouver in September as part of their Literary Arts Festival, and I’ll be pretty busy with teaching again in September, which takes up a lot of time.

There is the documentary I mentioned about our Uncle Emanuel that we need to sit down and edit (many, many hours of footage to sift through to put the story together). I also have a graphic novel project that’s been on the back burner that needs to be done asap.

I’d love to write those Y/A [young adult] novels I’ve had in the back of my head for awhile, plus the next novel that’s in an unfinished state. Too many unfinished projects! Dream project: finish these ones first before I tackle anything new.

CT: Have you or your family come up with any fusion Indigenous Jewish recipes?

NA: That might be a question for my brother Shawn – he’s the chef! Though, a lot of my knowledge of Jewish cooking comes from my mom, who learned how to do a lot of cooking from her mother-in-law. I think that’s a type of fusion. Learning how to cook Jewish food by way of my Anishinaabekwe mom – even my Jewish food is Indigenous.

Follow Nathan on Instagram @rivvenrivven or on Twitter @nathan_adler.

Carmel Tanaka is the founder and executive director of JQT Vancouver, and curator of the B.C. Jewish Queer & Trans Oral History Project (jqtvancouver.ca/jqt-oral-history-bc) and the Jewpanese Oral History Project (Instagram: @JewpaneseProject).